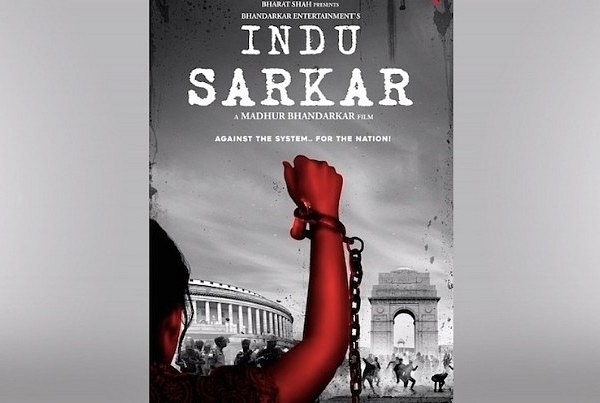

‘Indu Sarkar’ Revisits The Emergency Era

Indu Sarkar presents that grim reality of what happens when nepotism is unhindered and runs amok, and when favouritism supersedes meritocracy.

That the emergency was the darkest phase of independent India’s history is beyond debate. That the emergency threw basic human rights in the bin and resisted even protests with jail or murder is widely known.

That a few crony capitalists prospered through all this mayhem, just because of their proximity to the unconstitutional power centres, was always well-known in Lutyens’ circuits.

That all this happened, primarily to feed the ego of one woman and her wayward son, is already well-documented.

While many books have been written on the subject (by Kuldip Nayyar, Vinod Mehta, Coomi Kapoor, Nayantara Sahgal and Tavleen Singh, among others) Indu Sarkar is perhaps the first attempt at democratising the subject and making it available through a simpler and more accessible format – Hindi cinema.

Delhi “intellectuals” and Lutyens media-wallahs stood by cheering Sanjay Gandhi and V C Shukla (then information and broadcasting minister) as they burnt all prints of Kissa Kursi Ka, displaying temporary amnesia on the freedom of speech.

The same “intellectuals” and Congress party workers were violently against Madhur Bhandarkar and this film, which is a terrible metaphor for where the Lutyens’ intellectuals/media ecosystem is headed.

Thankfully we live in different times now, where we can see and hear the story that needs to be told.

The movie in itself is interestingly packaged as a first-person account of the Emergency. Indu Sarkar views India’s moment, just like Roberto Benigni’s “Life is Beautiful” viewed the Nazi atrocities on the Jews, from an individual’s point of view.

The movie covers the protagonist’s journey from enjoying the perks of prosperity and being a ‘casual, indifferent bystander’ to a ‘fully dedicated activist’ – a message many Indian citizens need to take away today.

The transformation of the protagonist isn’t driven by some personal tragedy or personal ideology. It is simply driven by her choosing to open her eyes to the atrocity around her. It is driven by her opening herself up to see the truth. One can’t but help draw parallels to the atrocities in Kashmir, Kerala and West Bengal and wonder when India will open its eyes to the atrocity.

Kirti Kulhari portrays her role ably and looks convincing across a range of personality types, from the meek, “mera pati mera devta hai” type to a roaring, guts-of-steel activist that boldly volunteers to walk into near-death situations. She, figuratively and literally, finds her voice after she stands up for what she believes in. This, then, is as much a story of women empowerment as it is about the Emergency.

Tota Roy Chowdhury brilliantly portrays a government babu, displaying all signs of entitlement and elitism, till reality hits home hard. In the scene where he walks into the market as a nobody, his reaction – a mix of frustration, surprise, sorrow, self-pity and self-loathing – is just priceless. He packages all of these emotions so beautifully well together, and all this without even uttering a sentence. This is an actor I would watch out for.

Neil Nitin Mukesh portrays the spoilt-brat scion of the family, for whom elections and democracy are, at best, a minor nuisance. It’s a tough job playing a narcissist, whose ambition far outweighed his sense of decency or respect for human rights. Mukesh’s character comes across as steely and ruthless, and as someone who rules with an iron fist while, on the flip side, is always seeking validation from this sycophants.

Anupam Kher, Sheeba Chaddha, Ankur Vikal, Parveen Dabbas all deliver on their roles. But this movie is not about stars or personalities. It is about recreating an era that has been systematically hushed up. The production design by Nitin Chandrakant Desai fairly accurately recreated a bygone era, with rotary telephones, Remington typewriters and Lambretta scooters slyly tucked away in the background. Keiko Nakahara’s cinematography adequately captures the urgency of the moment and the emotions of the characters.

Where the movie succeeds is in re-triggering forgotten memories of the Emergency. One can’t escape reliving moments one has only heard of.

Ten moments that stood out for me:

1. The unimaginable level of power Kamalnath and Jagdish Tytler wielded just because of their proximity to Sanjay Gandhi

2. How Rukhsana Sultana leapfrogged from sipping cocktails and fluttering her eyes in the Lutyens’ party circuit to virtually running the ghastly sterilisation programme

3. The brutal genocide at Turkman gate, and Jagmohan’s elevation for having delivered the operation to Chotey sahib

4. The petty revenge on Kishore Kumar for refusing to sing at the party function

5. The ignominy of I K Gujral’s dismissal just because he chose to express an opinion contrary to the first family

6. How government agencies like the Intelligence Bureau were redirected towards protecting ma-beta rather than the country

7. How JP turned the discourse global, by sending leaders like Dr Subramanian Swamy to build consensus internationally

8. The determination of George Fernandes in turning the protests violent, and his sheer brazenness when produced in court

9. How a bunch of crony capitalists leveraged political instability to their advantage, while others like Ramnath Goenka stuck their neck out for they valued our Constitutional values

10. Most importantly, how a bunch of rag-tag nobodies got together, simply for what they knew was right, and fell the powerful mother-son duo whose personal interests came before the nation’s

Indu Sarkar presents that grim reality of what happens when nepotism is unhindered and runs amok, of what happens when favouritism supersedes meritocracy, of how not just political parties but even the nation and its citizens suffer when putramoh exceeds all limits.