‘Naya’ Jammu And Kashmir: The Way Forward Lies In Tourism, Infrastructure

In the aftermath of the revocation of J&K’s special status, there has been a lot of talk about boosting tourism in the Valley.

But did you know that China did not envelop Tibet just by pure force? It also funnelled as many as 30 million tourists into the region in 2018, creating a $7 billion economic ecosystem.

In 2018, only 8.5 lakh tourists visited Kashmir.

Now that the dust has settled on the decision to make Articles 370 and 35-A redundant, the focus is starting to shift on the kind of development that can take place.

Especially since Jammu & Kashmir’s transformation is now set to occur under central rule. A lot of the speculation surrounding the way forward is ill-informed as it ignores critical limitations of the economy of J&K, namely its lack of natural resources, low population, distance from markets et cetera.

These are formidable barriers to quickly improving any the economy even if there is no militancy. Another error is thinking that the development has till now been state-led. In fact, the central government has been allocating 10 per cent of its funds, for a state with 1 per cent of India’s population.

Even before bifurcating J&K into union territories, 53 per cent of J&K's budget was met by central grants.

However, much is left to be done, and now with the centre officially in the driving seat, J&K’s economy and, consequently, India’s national security can be transformed by a few projects that are quickly achievable and do not involve any commitment of resources apart from that which is already budgeted for.

Tourism: While tourism is the biggest employer in the state, and normalcy expected to boost the sector, the biggest constraint has been the lack of transport connectivity with the rest of India.

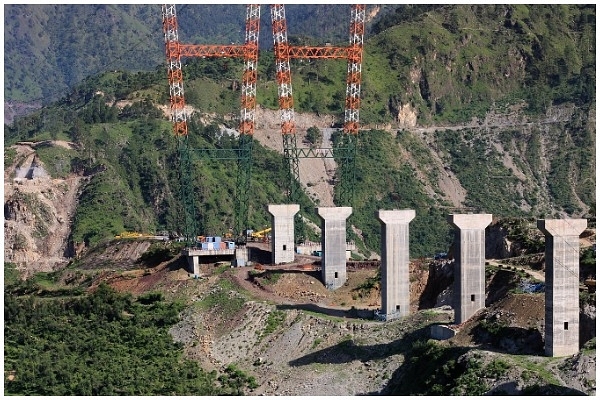

Srinagar remains unconnected by rail to Jammu. The Udhampur-Baramulla rail project looks set to miss its revised 2021 deadline for completion. This is after being late by 16 years with a cost overrun of over Rs. 25,000 crore.

The Chinese have been able to quell unrest in Tibet, not by force alone, but by increasing tourist numbers to over 30 million in 2018, with the introduction of high-speed railways. This is a 60- times increase from the 500,000 tourists that visited the region in 2001. Less than 10 per cent of Chinese tourist arrivals are by air.

These tourists spend over $7 billion (almost Rs 50,000 crore or 60 per cent of the total expenditure of the J&K government in the 2018-19 Budget). In contrast to Kashmir, this inflow of tourists is in a mostly barren landscape at very high altitudes. The real contrast, however, is in tourist numbers for Kashmir.

In 2018, only 8.5 lakh tourists visited the Valley. Although 2012 was supposed to be a boom year for tourism, it saw merely 1.3 million visitors. They included only 0.5 per cent of the foreign tourist arrivals in India.

In contrast, the Vaishno Devi shrine in Jammu (which skews total tourist arrival numbers in the state) had 10 times that number (85 lakh tourists) visiting. The difference is that Jammu has rail connectivity (up to Katra), where the shrine is located.

The Jammu-Srinagar rail project has, as its uncompleted part, a 111-km stretch between Katra and Banihal. The delay is not due to construction challenges, of which there have been many.

The cause for the delay is mainly the disputes between the contractors, and delays in land acquisition. The timely completion of the rail project will be a visible symbol of the benefits that the central government can bring.

However, for these benefits to fully accrue, the vision should be for a ten-fold rise in tourism, which requires an exponential increase in infrastructure. For example, a 10-time increase in skeletal train services from Banihal northwards, as well as in hotels along the line.

The development of roads alongside the rail line, connecting 79 villages, can be the ideal place for land acquisition for the development of tourism infrastructure.

This also ensures that Srinagar does not suffer the same fate as many overcrowded unplanned hill stations do, leading to tourism being concentrated only in Srinagar.

The extension of the rail project, connecting Anantnag with Pahalgam, and from Baramulla to Kupwara will further enhance tourism, as would the completion of the pending road projects.

The recently revived rail project connecting Bilaspur to Leh via Mandi will be a game-changer for the development of tourism in the areas of northern Himachal and Ladakh.

Besides tourism, the line will enhance national security due to the ability to move troops and equipment from Punjab to Ladakh. This will also be a better deterrence to Chinese designs than having men permanently stationed in the inhospitable terrain.

A project which can yield multiple benefits is the completion of the Tulbul barrage. The Tulbul barrage was stopped in the 80s because Pakistan objected to it, and later because of the threat of militant attacks.

Not only will its completion allow water transport from Anantnag to Baramulla, but will enhance power generation. In case of hostilities along the Line of Control, it will also enable India to control the flow of water into the Neelam valley in Pakistan. Given the political will, it can be completed quickly.

All airports in J&K (Srinagar, Jammu and Leh) are Indian Air Force bases. Civil aviation is allowed, albeit with restrictions that constrain the number of flights.

With land acquisition becoming easier, there is a case for Srinagar to have a larger international airport operating 24 hours, to attract charters and international flights. The existing airport at Srinagar can be used for smaller-capacity flights connecting more Indian cities directly with the Valley, bypassing Delhi.

This will take the load off an already saturated IGI Airport in Delhi as well. The airstrips at Thoise and Kargil can be used for civilian flights, making both these destinations a gateway for adventure tourism and an alternative to Leh, which has restricted flying hours.

Whenever there is a terrorist attack or another outrage by Pakistan, the media speculates about India abrogating or suspending the Indus water treaty, a treaty that gives Pakistan the right to use 80 per cent of the waters of the Indus river.

However, what is often ignored is that India does not even use what it is entitled to under the treaty. India does not use all the water storage and power generation that it is allowed to utilise under the treaty.

The completion of these power and irrigation projects will end power shortages in the state while ensuring availability of power for new industrial units that might be set up, thus easing Jammu’s water problems and providing India with more leverage over Pakistan.

Highly polluting leather tanneries which have affected the ability to clean the Ganga can be shifted to parts of Jammu and Kashmir.

Here, river water can be used without the risk of polluting river waters within India. This can be done by setting up (or shifting) processing facilities to Kupwara and Baramulla in the Valley, and Akhnoor in Jammu, just before the Chenab flows into Pakistan.

This can revive the almost dead Kashmiri leather industry, while better transport links will improve the market for its agri-produce. It currently costs less to import apples from China or New Zealand, for consumption in South India, than getting them from Kashmir.

The increase of seats in the J&K Assembly following its conversion to a UT also enables a more representative local government. A delimitation exercise that will precede the carving out of the new seats should redress the current imbalance wherein Kashmir has more seats than Jammu.

While the population of Kashmir is slightly more than Jammu, the area of Jammu is larger than Kashmir.

The delimitation process, which takes both population and area into account, should ideally give both regions roughly the same number of seats, making it impossible for any party to rule if they have a representation in only one of the areas (Jammu or Kashmir only).

Bringing in reserved seats and altering the boundaries of seats that had become fiefdoms of entrenched politicians will pave the way for a genuinely representative Assembly that is more focussed on development than on religious divisions.