An Interview With Prof Ramesh Rao: "North Indian Children Should Be Taught One South Indian Language Of Their Choice"

The Right People is a new interview/podcast series where we engage with individuals who are involved closely with the broader Right ecosystem. In this installment, we interview Prof Ramesh Rao.

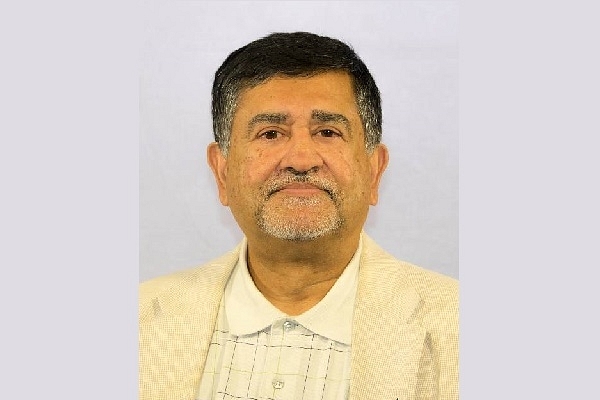

Ramesh N Rao, Associate Chair, Department of Communication, Columbus State University, reads into the ideological battles being played out in India’s socio-political scene, how social media has empowered the marginal voices and the need to remain attentive to the defamation campaigns run by the Left. Edited excerpts from a spirited email conversation with Antara Das:

Q: As a career academic in the US not sympathetic to the left, what have been some of the most outstanding challenges that you have faced?

A: I have voted for the Democratic Party candidates since I became a citizen of the US. I grew up in India under statist/Nehruvian dispensations. I am for gun control. I am for gay rights. I am passionate about saving and protecting the Earth. And, I pray both to Saraswati and to Lakshmi. So, to say that I am not sympathetic to the left or liberals would be to fall into the trap manufactured by my leftist academic colleagues, and their tribal identities and membership in specific groups.

While I don’t get to sup at the leftist high table, there are also advantages of not belonging to these groups in that I don’t have to mindlessly sign on to their various petitions against the BJP or the RSS or other Hindu-affiliated ‘villains’.

Q: Any challenge to the dominant leftist discourse always runs up against a targeted campaign of defamation and shunning. What are the possible ways of countering this well-oiled propaganda machinery?

A: The so-called left-liberal groups, though comprising a small section of the populace, have had the use of ideologies crafted in the West. They have learned to use them skilfully, ensuring that those challenging them would never be permitted to enter the battle arena. It is so in the US, and in Europe, as it is in India.

A Brown University professor bemoaned, recently, about ‘McCarthy like witch hunts’ that make free and open discussion about issues almost impossible in American universities. It is the same in British universities, and we know that Dr. Koenraad Elst was black-balled by his colleagues in Belgium for the work he has done on Hindus, the Sangh, etc.

Their fortresses were difficult to breach until social media began to open new frontiers. It may take a few years to see real progress but the battle is on. Meanwhile, one has to continue to be attentive to the shunning and defamation campaigns. Left activists are energetic, disciplined, and have vast resources, including the use of gullible graduate students to do some of their political dirty work.

Q: Your field of specialisation is communication. Is it possible, in your experience, to introduce students to ideas that do not lie within the strictly defined limits of Marxist or postmodern critical thought?

A: Sure, yes. In fact, till the 1980s there was a deep divide between scholars doing quantitative research (coming from a psychology/social psychology background) and those doing qualitative research (coming from an anthropology/ethnography background). Those doing qualitative research were not happy at the dominance of the social science/behaviourist approach to the study of human behaviour/communication.

The third group of scholars in the communication field are trained in what you would call the Marxist/critical approaches (including feminist theories). In the communication field, as in some other social science departments, the work is a little less ideological (compared to other departments in the humanities and social sciences).

This is because some of the well-established departments in the big research schools continue to maintain a grip on studying human behaviour and communication using quantitative methods. Marxist and critical approaches do provide some interesting and intellectually stimulating analyses of the human condition, but as they say, the proof of the pudding is in the eating.

So, when it comes to the use of these theories by academics studying India, we see a mismatch between their ideals and their proposals, and their selective use of their theoretical lenses and methodological scalpels to eviscerate India of its Hinduism and in their silent if not overt support of the extremist elements among the so-called minorities, and their agendas to break India.

Q: The Indian diaspora in the United States is feted as a success story. Yet you have repeatedly warned of an increasing incidence of the distinct ‘Indian’ identity being subsumed under a larger ‘South Asian’ umbrella. What might be the implications of such subtle changes in identity and nomenclature?

A: I wrote an essay for The Subcontinental titled, ‘It is India, Not South Asia’, I argued that it was always an Indian/Indian-American initiative to buy into the South Asia moniker, and that none of the people from other South Asian countries paid much heed to it or found any purchase in it, except when they wanted their grievances against India and Hindus to be aired through these ‘South Asia’ groups.

It is strange that those who embrace the South Asian moniker don’t make a fuss about Pakistanis, Sri Lankans and Bangladeshis going their own way to build pressure groups in Washington DC, and to retain their own identity, except maybe when Bangladesh-origin entrepreneurs want to open ‘Indian restaurants’ in New York City!

Q: You have written about the splendour of Hampi’s ruins, and how the historical sites of southern India are often eclipsed by the prominence of their northern counterparts. What ways would you suggest to address such an imbalance?

A: The North-South divide in India is real, and it was starker when I was growing up – with the power and impact of the use of Hindi, the capital being situated in Delhi, and the privileges that accrued to people from proximity to the capital. One hopes that now, with increased wealth and opportunities for travel, use of social media, people will begin to learn about others beyond the Hindi belt and Bollywood.

I know Bengalis complain about being left out of the game or being part of the B team, so imagine how we South Indians feel about the ignorance of North Indians about the ways of the Southerners. As a young boy, listening to national news on All India Radio, I would cringe when the newsreaders botched the names of South Indian politicians or artists. It seemed as if we lived in two countries.

There are ways of addressing the imbalance, and I say this both in jest and seriously:

1. North Indian children should be taught one South Indian language of their choice.

2. North Indians who make their home in the South should learn to speak the local language: I cringe when I visit Bengaluru, my hometown, and almost immediately the taxi driver mistakes me for a North Indian and begins to talk to me in Hindi.

3. Rewriting and updating Indian history books for children such that all parts of the country are equally highlighted.

4. Carnatic music should be offered compulsorily in schools in the North, as well as various South Indian dance forms.

5. Rajnikanth be made Brand India ambassador.

6. Masala dosa be declared the national dish.

7. Every North Indian bureaucrat, who has access to ‘paid travel’, visit a South Indian destination, on alternate years.

8. Every AIR and Doordarshan announcer be made to learn by rote the proper pronunciation of Venkaiah Naidu, Deve Gowda, Subbulakshmi, Umayalapuram Sivaraman, etc.

9. The summer capital of India be shifted to Mysuru.

10. Every North Indian child be taught that it is both Ram and Rama/Raman, Lav and Lava, Kush and Kusha, and Arvind and Aravinda/Aravindan.

Ramesh N Rao’s latest books include The Election that Shaped Gujarat & Narendra Modi’s Rise to National Stardom (Mount Meru Publishing) and Intercultural Communication: The Indian Context (Sage), with Avinash Thombre