Book Review: Shantanu Gupta’s Latest Tracks The Journey Of A Mass Movement That Awakened People To A National Vision

BJP’s functioning as a political party and its growth as a mass movement that awakened people to a national vision are traced in the book.

It looks at the BJP as a movement critically, but positively.

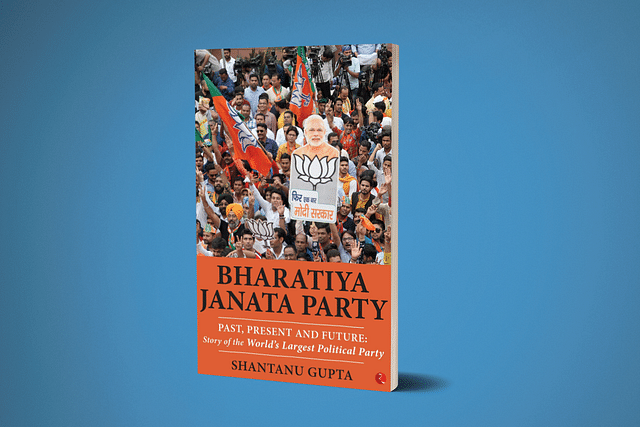

Bharatiya Janata Party: Past, Present and Future: Story Of The World's Largest Political Party. Shantanu Gupta. Rupa Publications. 2019. 416 Pages. Rs 695.

This book ostensibly speaks about a political party that is ruling India today, but it places the discourse in the context of a civilisational battle.

It starts with how foreign aggressions against India have always gone beyond attempts at mere political subjugation. They were aimed to destroying dharma, the heart of the civilisation, by destroying the institutions of culture.

Shantanu Gupta, the author, unveils a golden past of an India, where differences could coexist, and the education system was cost-effective, egalitarian and democratic.

Of course, leading author Dharampal serves as the authority. The battle for the souls continues to this day. The emergence and functioning of Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) is explained as the Indic resistance in this historical context. It is this that sets the party from being just another party.

To whom shall the book appeal?

The problem here is that many of the facts that the book talks about would have been already felt by every Indian almost intuitively but yet most would not know how to substantiate it.

So, in a way this book provides ammunition of data to these people who form the major chunk of the BJP supporters. It assumes that the reader is already on the side of the author, and provides data to substantiate their inner convictions.

Consider, for example, the case of appeasement policy of Islamism.

How did the British indulge in it?

The author points out that Lord Northbrook donated Rs 10,000 to a college started by Syed Ahmed that would later become Aligarh Muslim University (AMU), and no such support was coming for Hindu endeavours (Page 35).

Everyone knows the kind of ‘Bhagirathic’ efforts Madan Mohan Malaviya had to undergo for establishing Banaras Hindu University (BHU). Yet, in today’s pseudo-secular false symmetry, we see BHU getting equated with AMU.

The book is divided into three parts: first deals with the Arya Samaj and Hindu Mahasabha during the colonial period before the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) was started, and then the formation of the RSS and its worldview as well as its methodology of concentrating on the individual. It ends with the RSS facing the ordeal of fire namely facing the false accusation of complicity in Mahatma murder.

In the second part, the emergence of Bharatiya Jan Sangh (BJS) is described in detail. M S Golwalkar was not at all interested in getting dragged into politics.

However, there was the problem of looming genocide over the 'East Pakistan' Hindus. Particularly telling is the enormous human tragedy of Hindu refugees from East Bengal and the indifferent attitude of Jawaharlal Nehru towards their plight.

Shantanu Gupta describes this in detail:

According to a Times of India report published on 9 October 1950, between 10 and 20 February, 10,000 Hindus were killed. The Pioneer, on 22 May 1950, reported that 860,000 Hindus came to India as refugees in just the past two months. Since the day Nehru had signed the pact on 9 April till 25 July, according to The Statesman dated 2 August 1950, 13,00,000 Hindu refugees had entered West Bengal. (Page 137)

At the same time Nehru was also systematically marginalising and stifling even in a totally undemocratic way every pro-Hindu Congress leader including Purushottom Das Tandon.

It was under such circumstances that Dr Syama Prasad Mookerjee could convince a reluctant Golwalkar that a political party was indeed needed.

BJS was qualitatively different from the rest of the polity, and the author quotes Balraj Madhok, who stated that the difference BJS had with the rest was "one of the principle and not of policy".

The book brings out both the seminal role played by Madhok in pressurising the RSS leadership to lend its support and human resources to a political party, his importance in drafting the formative documents of the party and his uncomfortable feeling at creating alliance with other parties on a purely anti-Congress agenda, and later how he became a ‘problem’ in the evolution of the party.

The book could have mentioned his important contributions which were later adopted by Lal Krishna Advani in the name of cultural nationalism — ‘Indianisation’.

Unfortunately, Madhok made himself irrelevant by his maverick statements. Yet his contribution should be remembered with gratitude. This book does make an initial attempt at it.

The next major milestone in ideological narrative of Hindu national movement is Deendayal Upadhyaya’s ‘integral humanism’. It is still a vision that has not yet found its complete significance. It has an eternal value. Upadhyaya, in fact, through ‘integral humanism’ brought in rishi-vision to Indian polity.

The author allocates just three paragraphs to this concept. He could have given more space to it, and could have thrown light on the circumstances and events that surrounded the emergence of this vision in Upadhyaya. Compared to 'integral humanism’, ‘Gandhian socialism’ with which the party later flirted with, was at best a bad joke to be forgotten.

There is a particularly interesting narrative in the book — it is about the emergence of Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) as a Left bastion.

The author brings out, very convincingly and with evidence, how the stranglehold that the Leftists have on our educational system was an institutional concession Indira Gandhi gave to the communists in exchange of their support against great savants of old Congress like "K. Kamaraj, S. Nijalingappa, S.K. Patil, Atulya Ghosh and N. Sanjeeva Reddy" who were insultingly nicknamed as ‘Syndicate Congress’.

It was in this context that JNU was made into a Leftist indoctrination centre luxuriously nurtured by Indian taxpayers’ money. The so-called academic freedom of JNU was actually allowing Left-wing indoctrination in exchange of communist support for a corrupt dynasty politics defeating the last vestige of honest and patriotic leaders in the original Congress (Pages 202-204). This in itself could be and should be elaborated into a book — and it will definitely read like a thriller.

The book rides on two tracts — it tracks the development of the BJP as a political party with full data tables of how its fortunes fluctuated and it also shows how the BJS to BJP leaders also through mass movements awakened the people to the national vision which distinguished the party from the rest.

The author weaves it almost seamlessly. Whether it is resistance to Emergency, Ayodhya movement, Kashmir issue, nuclear policy or the problem of refugees, BJP alone seem to possess an alternative vision. And they move towards articulating it despite the entire polity standing against them. But they have made it possible.

After doing all the groundwork through rath yatra and making the entire nation question the fundamentals of a flawed version of secularism, Advani announces Atal Bihari Vajpayee as prime ministerial candidate. Vajpayee with his adorable innocence, yet unmatched statesmanship, takes India into the nuclear club.

He also ‘superhumanly’ manages the mighty contradictory coalition without giving into monumental corruption. More importantly, a swayamsevak had become the prime minister of India with the support of a mostly non-Hindutva parties. A major mental block in the collective Indian psyche conditioned by Nehruvianism had been broken.

From the 13-day government in 1996 to six-year government between 1998 and 2004, this was a major victory for not just BJP, the party, but for the ideological movement behind it.

One can see that many of the present-day BJP leaders have emerged from the workers of the previous generation leadership. Whether it is Advani or Murali Manohar Joshi or presently Narendra Modi, the next leader who emerges is almost unknown and comes to the fore through sheer hard work as well as commitment to the national vision.

Here is then a party dedicated to a national mission where leaders have to see beyond narrow self-interest and even narrow political gains if they have to emerge as leaders.

At last, the book establishes the present leadership as the continuation of this grand process that started with Arya Samaj and Hindu Mahasabha during the colonial struggle to the present-day BJP.

There are many books which analyse BJP and its ideology. Most of them are critical and negative. This book looks at the BJP as a movement critically, but positively. This book has indeed done a commendable job.