Book Review: Ted Chiang Uses Sci-Fi To Present A Nuanced Understanding Of Our Own Selves

It has become very important to engage in science fiction more than ever before.

As learned from influence of the Foundation series, Star Wars and Stanley Kubrick movies on the subsequent developments in space exploration and robotics, art precedes science and imagination precedes logic.

Exhalation. Ted Chiang. Picador. Rs 353.29 (Kindle Edition)

On the recent Chandrayan mission, the Indian Express wrote, “The lander was being guided to the surface of the Moon by an Inertial Navigation System on board, in which Vikram was taking decisions by itself, without intervention from ground stations, on the basis of data obtained from cameras, sensors, and altimeters on board.”

It did not catch much attention that the moon-bound machine was an intelligent and self-learning one.

Sans the mishap, we could have seen the landing of Vikram and the movement of the Pragyan rover. And quite possibly, we would have fallen in love with the intelligent moving object. Alas! Many in ISRO and the scientific community would have already given a piece of their hearts to Vikram and Pragyan as if they are sentient beings. Not unnatural for a country that celebrates “Ayudha Puja” and for a species with a subset that treats bikes and cars as more than just property!

The future is upon us and many writers are helping draw the moral contours of the new world. Hence, it has become very important to engage in science fiction more than ever before. As learned from influence of the Foundation series, Star Wars and Stanley Kubrick movies on the subsequent developments in space exploration and robotics, art precedes science and imagination precedes logic.

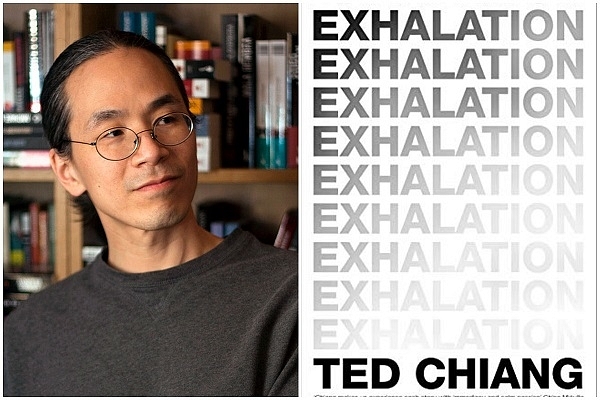

In this milieu, superstar sci-fi author Ted Chiang has released “Exhalation”, his short-story collection. The author has won an array of awards including the Nebula and the Hugo. The Amy Adams movie “The Arrival” was based on his work. The stories in “Exhalation”have been written over the last two decades. The endnotes give us a peek into the magical ecosystem of sci-fi enthusiasts and a glimpse of the author’s collaborators.

“Exhalation” educates, teases and thrills in equal measure. Every short story is imaginatively plotted. Quite strangely, the settings in imaginary worlds allow us to grapple with the ethical intricacies more freely. The reader will more often than not stop and ponder over the deep insights and the moral dilemmas. There is science, but the stories are meditations on human nature.

The author keeps the prose simple, almost reminding us of Haruki Murakami, who pulls the heartstrings with simple phrases. Chiang erects the scientific settings with precision. He then deftly takes us into the geeky worlds with cleverness and compassion. Once we familiarise ourselves with his imaginary world, he feeds us with grand thought experiments.

The standout story is the brilliantly crafted, “Lifecycle of Software Objects”. Here the protagonists rear digital pets called digients. Over long years, they grow affectionate towards these pets that develop intelligence of their own. The changes of technology platforms pose existential threats to the digients. The “parents” of various digients frantically discuss on online forums on what is good for them. They agonise about whether digients have to be “incorporated” by giving them legal rights, and thereby leaving them on their own just like human adults. The reader is cajoled to wonder if digients are just robots or pets or children. Through these digital objects, the author posits several thought provoking questions on parenting, education and loyalty.

In “The Truth of Fact and Truth of Feeling”, the author tells two tales in parallel. One is set in the past, in a tribal enclave that is introduced to a new technology, namely writing. The other is in the future, where “life-logging” or video-recording of everything has become fashionable. In the tribal society both facts and what is contextually correct are considered as truth. The written word challenges this notion. In the story set in the future, the chief protagonist believes that he has made peace with his daughter, who he remembers as having said hurtful things to him in the past. When he rewinds his life-log, he is gutted to find a different version of the story. If the fuzzy memories that allow us to heal from traumas are replaced by the “objective truth”, do we still remain the humans that we are? It gives us much to ponder on the fallibility of memory, linguistic imprecision and social trust. It rudely reveals to us to those flimsy assumptions that we make for ourselves to just get by in life. He reminds us that we became “cognitive cyborgs as soon as we became fluent readers.”

In “Omphalos”, Ted Chiang carries us along an archaeologist’s obsession with primordial creatures, which God has created Himself, such as, the mummy without the navel, the piece of wood that has no rings in the core to denote the age or shells of clams that have no lines etc. Her notion of archaeology being an instrument to discover the great manifestations of God’s work is hit by a crisis, when she learns about another planetary system, where the sun goes around the planet! The role of religion in giving meaning to the great mysteries is quite imaginatively brought out.

“The Merchant and the Alchemist’s Gate”, lacks the technical wizardry of the other stories. Set in the Arabian nights tenor, people travel into the past or the future to understand more clearly on what transpired during those times. The protagonist poignantly learns that, “Nothing erases the past. There is repentance, there is atonement, and there is forgiveness. That is all, but that is enough.”

There are a couple of very short pieces. In the “Great Silence”, a Puerto Rican parrot laments that while humans have sent out signals to communicate with aliens in other parts of the universe, they have failed to engage with parrots that can talk and understand. “What is Expected of Us” is a quirky take on the free will versus. determinism debate through a gadget called the “Predictor” that flashes light a second before one presses the button on it.

There is a story of the “Automatic Nanny” set in the 1900s. After the initial success, a robotic nanny machine is discarded after a child under its care dies. The inventor’s son revives the project to rear his own child. The child develops psychological dwarfism that people blame on lack of human contact, only to realise later that the actual cause was the robotic nanny being taken away at a crucial point. In the endnotes, the author tells us that the great BF Skinner had actually designed a similar contraption.

In “Exhalation”, a robotic citizen of the future realises that the survival of the species is based upon the pressure differential between inhalation and exhalation. The fear of entropy hurtling the species to doom, prompts the robotic citizen to perform self-surgery to understand the inner process further.

In the last story, “Anxiety is the Dizziness of Freedom”, people access parallel versions of their lives starting at various points. They communicate with those “para-selves”, triggering many existential crises such as anger, jealousy, sometimes friendships between the versions of their own selves. The moral weight of an action becomes warped and people start making decisions with the knowledge that in another parallel universe, they would be unaffected by consequences. The author advocates principles of acceptance and responsibility through the character of a therapist.

“Exhalation”has more on humanism that science. It is as much a book of sociology, philosophy and psychology as science fiction. Through interesting scientific props, it is a meditation on the human condition going beyond futility and nihilism. It is ultimately human sensitivity, love, dignity, tolerance and fortitude that redeem us in situations that render us almost powerless.

Indian sci-fi writers and movie-makers should engage with these concepts more eagerly. The puerile idea that there has to be a physical robot with LED eyes has to be re-examined. As Chiang teaches us through these stories, there is lot a more than scientific allure to sci-fi. The binary utopian-dystopian praxis has blinded us from using sci-fi as a scaffold to a more nuanced understanding of our own selves. That is the opportunity that Ted Chiang is offering us.