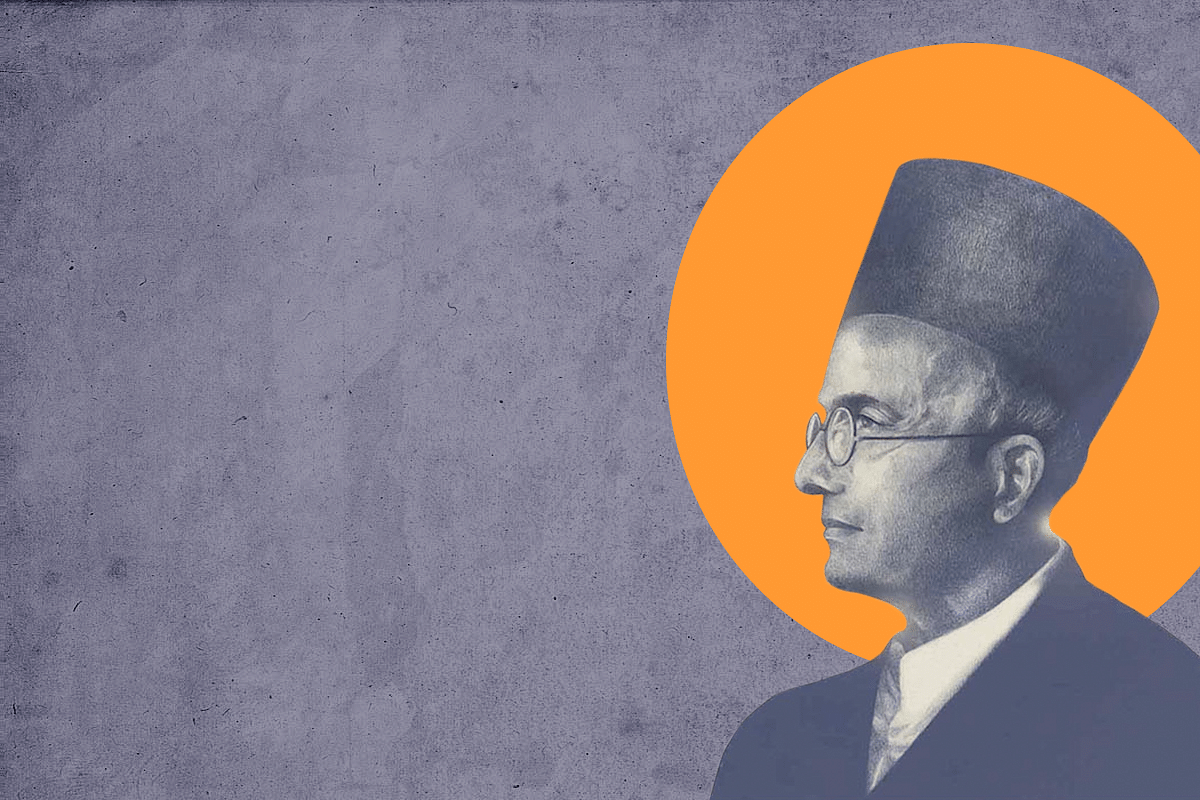

How Savarkar Transformed From A Radical Anti-Colonial Revolutionary To A ‘Hindu Hriday Samrat’

Two recent books on Savarkar explore the genesis of his philosophy and describe in detail how a radical anti-colonial revolutionary transformed into a ‘Hindu Hriday Samrat’.

Savarkar: Echoes From A Forgotten Past - 1883-1924, Vikram Sampath, Penguin, 624 pages, Rs 800.

Savarkar : The True Story of the Father of Hindutva, Vaibhav Purandare, Juggernaut, 360 pages, Rs 478.

Veer Abhimanyu is the tragic hero of tragic heroes of the Mahabharata. Every Indian grows up listening to his tale of valour and sacrifice on the battlefield. Before Abhimanyu enters the dharmakshetra Kurukshetra, we are told, elders shower their beloved child with various blessings — some wish him victory and some long life.

But Bhagwan Krishna, his maternal uncle, cannot not be prophetic. “Yashasvi bhava” is all he has to say to the brave warrior. After all, even evil men can win in battles sometimes. Many adharmis may live long lives. But only the worthy attain yash, which is permanent, with time their witness and a grateful nation to propagate their gaathas generation after generation.

Veer Savarkar, the tragic hero of India’s Independence movement, was even more unfortunate than Abhimanyu. He didn’t have the luxury of sacrificing his life in one battle. He had to fight many. His struggle was stretched over decades. Perhaps, that’s why he is despised so much.

His detractors would’ve liked him much better had he died a brash revolutionary, to be ceremonially garlanded on birth and death anniversaries and forgotten for the rest of the year. But he committed the unpardonable sin of giving the nation an idea.

An idea of India which is growing stronger by the day and tormenting them no end.

Savarkar didn’t get his due during his lifetime. Heck, he was denied that until long after his death. It’s not that the State contested his contribution. Worse, it simply ignored it. While the State tried to forget, the nation didn’t.

It couldn’t afford to.

The gods have promised the worthy their eternal yash. And they shall have it.

After more than half a century of wait, two English biographies of Savarkar have come out this month. While the one by Vikram Sampath (first part of two-volume tome) is more thorough and academic in nature, Vaibhav Purandare’s book is more concise and to the point.

The latter is more focused on analysing his subject and his views, while Sampath dives deeper in detailing the events precipitated by Savarkar and numerous people he influenced and inspired through many institutions he built and nurtured (Mitra mela, Abhinav Bharat, India House, Hindu Mahasabha, etc).

Sampath writes like a historian, Purandare like a journalist — both true to their craft.

Both deserve plaudits for capturing the evolution of the man and his ideas and the reasons behind them. Good biographies are all about going beyond the simple, chronological retelling of events.

As Jaideep Prabhu writes:

Any serious author must peel back the layers of the contemporaneous and reveal what motivates his subject.

Sampath and Purandare have succeeded in doing exactly that.

This is what makes their works extremely important. When I picked these books, I wanted to understand how, why and when Veer Savarkar, the young, radical anti-colonial revolutionary ended up becoming a Hindu Hriday Samrat. My curiosity is now satiated.

Both personal and political experiences shaped Savarkar’s views regarding Islam and Muslims, but the genesis of his transformation, as is the case with most Hindu nationalists, lies in appeasement of the Muslim community by the government of the day.

In 1894, as Bal Gangadhar Tilak throws his weight behind grand Ganapati celebrations and religious processions, they instantly become a contentious issue between Hindus and Muslims and lead to conflict between the two communities.

Not surprisingly, pig-cow are thrown into the communal cauldron and riots erupt in the Bombay Presidency.

Tilak, via Kesari, takes the government to task for only clamping down on Hindus and appeasing Muslims. As a 11-year-old in his hometown Bhagur, Savarkar and his friends, regular readers of Kesari and other such nationalistic publications, are incensed with the riots and decide to avenge them.

They launched a secret attack on a local mosque in the dead of the night and damaged some portion of it.

According to Purandare, this doesn’t prove Savarkar was anti-Muslim at this stage of his life.

“For one, he was but a boy. And the march on the mosque was more likely a classic example of what could happen to someone in the middle of a communal conflagration, when sentiments of a sectarian nature are running especially high. Such effects of group hysteria on otherwise reasonable individuals we have seen before Savarkar’s time, and after.”

However, there is more to the story than Savarkar merely acting mindlessly when passions were running high.

Quoting his memoirs, Sampath shows what lessons Savarkar drew from these experiences of riots: that Hindu society was riven with divisions and thus highly vulnerable to attacks. The young “Vinayak decided to establish a ‘military training school’ of sorts to instill a sense of discipline, rigour and commitment among his group,” Sampath writes.

Towards this end, he and his friends would divide themselves in two camps — Hindus versus British/Muslims and indulge in play acting, with Savarkar making sure the former came out on top always.

While this doesn’t establish at all that anti-Muslim feelings had seeped into Savarkar at this young age, constant hostility of the British and Muslims towards Ganapati and Shivaji festival celebrations must’ve left a bad taste in his mouth.

If there is any doubt left about Savarkar’s feelings regarding Muslims, then his book on 1857 revolt titled The First Indian War Of Independence should remove those. He ‘hailed the uprising as as an outstanding example of Hindu-Muslim unity’ and ‘lavished fulsome praise on the Muslim heroes of 1857 such as Awadh ruler Wajid Ali and Rohilkhand rebel chieftain Khan Bahadur Khan’, Purandare writes.

Sampath reminds us that Savarkar thought that post-1857, India was “the united nation of the adherents of Islam as well as Hinduism’.

Savarkar reasoned that as long as Muslims lived in India like the alien rulers, Hindus couldn’t accept to live with them like brothers as it would show weakness on their part, but now that the Muslims’ rule is destroyed by Hindu sovereignty after a struggle of centuries, there was no national shame in joining hands with Muslims.

“So, now, the original antagonism between the Hindus and the Mahomedans might be consigned to the past. Their present relation was one not of rulers and ruled, foreigner and native, but simply that of brothers with the one difference between them of religion alone. For, they were both children of the soil of Hindusthan. Their names were different, but they were all children of the same Mother; India, therefore, being the common mother of these two, they were brothers by blood,” Savarkar wrote.

Reading this, how can one accuse Savarkar of harbouring anti-Muslim feelings?

Purandare and Sampath both cite Savarkar’s speech at Nizamuddin’s Indian restaurant given in presence of Gandhi in 1910 to indicate that Savarkar had come to believe that reconciliation was possible between Hindus and Muslims.

“Hindus are the heart of Hindustan. Nevertheless, just as the beauty of the rainbow is not impaired but enhanced by its varied hues, so also Hindustan will appear all the more beautiful across the sky of the future by assimilating all that is best in the Muslim, Parsi, Jewish and other civilisations,” Savarkar had said.

Clearly, even in 1910, Savarkar believed that Hindus were the chief claimants to the Indian nation even though he celebrated diversity and far from being an exclusivist, his idea of a nation had a place for people of all faiths.

Both Sampath and Purandare trace the change in Savarkar’s focus towards Hindu causes to his experiences in the Cellular jail in Andaman.

“The first thing that one noticed in the jail was the distinction made between the Hindu and non-Hindu prisoners with regard to their religious traditions. On entry into the cell, the first act that was committed for a Hindu prisoner was that his sacred thread was cut off. However, Muslim prisoners were allowed to sport their beards, as were Sikhs with regard to their hair,” Sampath narrates of the prison scenario.

Most of the staffers who looked after the prisoners were Muslims. Their fanatical displays of religiosity and brutality against Hindu prisoners knew no bounds. Pathans, Baluchis and Sindhis were the worst.

They would mete out horrible treatment to Hindus and were in the business of converting. Those who converted would be treated leniently. To counter this carrot-and-stick approach to forced conversions, Savarkar launched his own shuddhi movement (re-conversion) in the jail.

Muslim prisoners would disturb everyone’s sleep early morning with loud Quran recitals. The jail authorities didn’t stop them until Hindus also started blowing conch shells in retaliation.

While Savarkar was lodged inside the jail, Indian polity was fast surrendering to Muslim League’s veto, starting with separate electorates under so-called Morley-Minto reforms and then Congress’ capitulation in front of it by signing the Lucknow pact.

Gandhi’s headlong dash towards Muslim appeasement post-Tilak’s death proved disastrous. His ill-conceived Khilafat movement was severely criticised by Savarkar, who termed it ‘aafat’ meaning trouble.

The fervour of millions of Muslims clamouring for re-instituting a Caliphate (Khalifa) in faraway Turkey also reminded him of their foreign allegiance. This must’ve played an instrumental role in him coming up with the definition of Hindu as ‘someone who considers India as both its fatherland as well as holy land’.

As Sampath concludes, “It was in the dark confines of the Ratnagiri prison that Vinayak began writing his magnum opus on his political philosophy — his conception of what constituted a ‘Hindu nationalist identity’. These were distilled from his experiences in the Andaman and Ratnagiri jails with respect to the conversions, his own attempts at shuddhi and sangathan and the raging debates in the country surrounding the Khilafat agitation.”

The rest, as they say, is history.