How Kirloskar Fought Against Impractical Gandhism

In his autobiography Cactus and Roses, legendary entrepreneur and industrialist SL Kirloskar talked about the times through which he lived, from the political and economic domination by a colonial power to the mistaken ideology that stifled the country’s growth after independence.

From the moment when, after my return from USA [end of 1926], I experienced my first direct contact with the current political movement in India, I became conscious of the serious differences I had in my thinking, that set me apart from my fellow citizens.

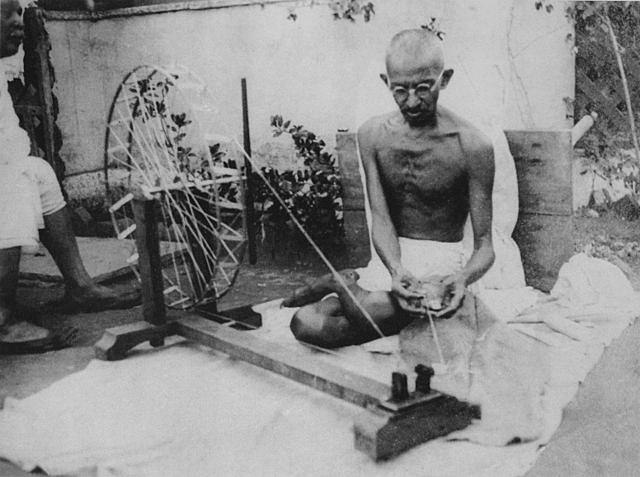

Although by no means deficient in the patriotic desire to see my country free and strong, I had my own views about the right methods of making her so. I regarded such rituals as the weekly Prabhat Pheries, the singing of patriotic songs, the parading of the Tricolour, even the wearing of Khaddar and spinning on the Charkha, in a detached and unemotional way. As I saw it, India’s political aim had already put her economy on the road to progress. The improved yield from farm-land created employment and turned out trained, well-paid workers able to raise healthy and educated children for the next generation, making a solid contribution to India’s economic growth.

Such contributions, in my view, could not be made efficiently—if at all—without the aid of machines. And here lay the heart of my difference of opinion with Mahatma Gandhi and his followers. Like Papa [Laxmanrao Kirloskar] before me, I am, have always been and shall always be, a ‘machine man’. I see the machine as a friend and helper of man, not as a demon devised for man’s economic and spiritual destruction, which is the way Gandhians regard it. Our own experience had conclusively proved the benefits which thousands of farmers derived from our ploughs, our pumps, our crushers and shellers and other labour-saving devices. Were we now to scrap all these benefits and revert to the traditional reliance on human and animal muscle-power, with all its slowness and inefficiency? No. A hundred times No! On the contrary I was convinced that India needed machines and prime movers in thousands. And what applied to agriculture, I would equally apply to textiles. If pumps and cane-crushers and groundnut-shellers were good for our economy, could spinning-frames and power-looms be bad? I could find no virtue in the slow and tedious spinning of yarn by human finger-power.

Though without the least desire to lead a crusade against what I saw as a Gandhian heresy, I allowed myself to argue this topic with our visitors, many of whom happened to be devoted followers of the Mahatma and hence bound to disagree with me. Some of them were thinkers, intellectuals and writers who contributed to our Kirloskar magazine, which Shankarbhau had developed into a very influential journal. The thinkers claimed that such practices as wearing Khaddar or remaining half-clad, were gestures which identified the leaders as one with the masses who never had enough to eat or wear. Living a simple life and keeping the body half-clad, they claimed, was a necessity. They argued that the Charkha employed more hands: spinning and weaving mills, fewer. When I asked what would happen if everybody spun his own yarn and wove his own cloth, they replied that it would make all of us totally self-reliant.

“Should an engineer waste his time in spinning?” I would ask.

“No, but he can buy from those who spin and weave,” was their usual reply.

“He already does so, but he buys what has been spun and woven in the mills.”

“But they employ less people because they use machines.”

“I think they employ more people at each stage, from spinning to the making and selling of cloth. Because more cloth is available, more clothes are stitched and so the tailors get more work. Again, making textile machinery employs more people in scores of processes from designing to erection and maintenance; it is a chain of manufacturing which employs millions. How can wooden charkhas and hand-spinning and hand-weaving increase employment?

Such questions tended to be shrugged off by the Gandhians and the argument would usually end by my being dismissed as a man ‘obsessed with American ideas’.

Such discussions moved me to a deeper examination of the logic of ‘Gandhism’, the name by which this philosophy was then known and under which it is still being propagated. My discussion with such men as I have described, revealed their claim that following Gandhism would achieve both spiritual and material progress for our people.

The high-minded but impractical thinking of these idealists underlined the traditional beliefs in our political movement of the 1930s. I listened to many speeches in which even academically well-qualified persons assured their large audiences that by following the Gandhian way of life, the people of India would be re-creating the blissful existence of the legendary Ram Raj.

Ram raj, indeed! What did this legendary Golden Age have in common with railways, roads, textile mills, telephones and so on which we already possessed in the 1930s? These Gandhian idealists seemed to me to be blissfully ignoring not only the facts of past history but also the realities of today. When India came under the control of Britain, it was a case of a country without machines being overpowered by one which had them. To discard machines, go about half-naked, live half-starved and reside in rude huts, would never lift us to the heights of happiness and freedom, but rather plunge us into the depths of misery and degradation. I, therefore, resolved to concentrate on the sound management of our enterprise, build more and still better machines, create more jobs and leave politics to our politicians. I would serve my country and lift her out of poverty and bondage, in the manner, which to me, seemed wisest, best, most efficacious, and most efficient.

Excerpted from Cactus and Roses: An Autobiography by SL Kirloskar (Macmillan)