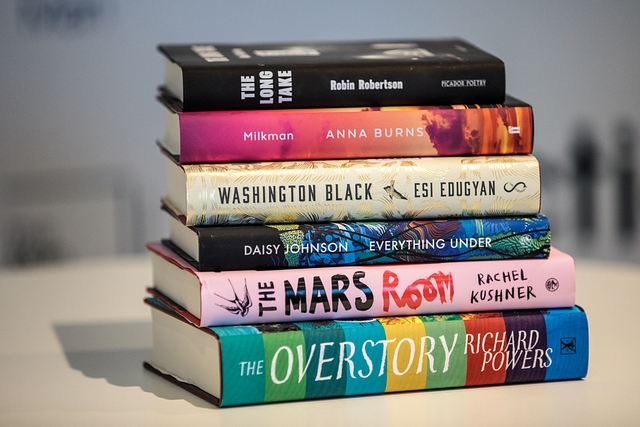

Man Booker Prize 2018: Why Anna Burns And Robin Robertson Are The Favourites

Here is a quick look at the books in the shortlist that would be an enriching experience, and the ones that are completely avoidable.

The Man Booker Prize for Fiction is the most well-known and widely-regarded literary award on the planet. This year’s prize will be announced on 16 October from among a list of six novels that made it to the shortlist. It is no surprise that in a time of #metoo five out of six novels shortlisted for the Booker this year give voice to unspoken forms of violence centered around gender and race while the sixth one is about climate change. No Asian or African writers made it to the shortlist this year, which too reflects in the themes addressed by the writers.

Read on to find out more about which ones are worth spending your time on, which books would be an enriching experience, and which ones are completely avoidable.

The Overstory – Richard Powers

Richard Powers is an American writer, whose work straddles the boundary between science, technology and literary fiction. A former computer programmer, his previous fiction has explored themes as different as artificial intelligence, virtual reality, physics and genetics. Known for seamlessly wedding science and literature, Powers’ novels unfold across grand canvases, spanning continents, and centuries. He is a winner of the National Book Award, America’s premier literary award.

With The Overstory, Powers has turned his formidable skill to trees and climate change. This result however, doesn’t quite match up to what one has come to expect of him. Powers’ 500-page saga reads more like a horticulture manual than a novel. Its tone is preachy, beseeching to the point where it begins to sound like white noise to the reader. The characters all seem like an afterthought, cardboard cut outs lazily drawn out to fit into the otherwise very relevant message that Powers wants the reader to pick up – we need to act now to save the trees. He just seems to have picked the wrong medium to put it across. If someone loves literature enough to pick up one of his books, they are most likely already convinced that the planet is in dire need of saving.

For an Indian reader, Powers’ poorly-researched insertion of the mandatory Indian stereotypes is another trope that irks. There’s the geeky Indian tech genius who makes a videogame that becomes a smash hit and turns him into a teenage billionaire overnight, and who inexplicable calls his father ‘pita’ (what can we make from this pita?) There’s Vishnu with his many avatars and blue-bodied gods that float in and out of the story, arranged marriages and visions, holy trees, obsessive-pesky parents, the works.

Matters aren’t helped much by Powers’ profligate use of the superlative either – each tree in the novel is described again and again as the oldest, tallest, wisest, strongest, ‘older than America itself’, ‘half as old as Christianity’ and so on. Repetition is the bane of The Overstory – by the time you’re half way through the novel, you’ve lost count of the number of times Powers has used the phrase ‘the most wondrous product of four Billion years of life’ to describe the Earth’s flora.

As for the story, there’s a confused, lazily sketched, and vastly stretched plot about a disparate group of people who are drawn together in a battle to prevent corporate logging in America. One learns a lot about trees, from Powers. For instance, how clearing virgin, untouched forests and replacing them with plantations is never a good idea, and why the world needs virgin untouched forests. As an engaging work of fiction though, The Overstory is sadly wanting.

Washington Black – Esi Edugyan

‘You took me on because you were more concerned that slavery should be a moral stain on white men than the actual damage it wreaks on black men.’

The protagonist in Washington Black beseeches his one-time saviour – white man – in the middle of the Sahara desert in Morocco in this novel about race and human ingenuity.

Like Richard Powers, Canadian Esi Edugyan is an artiste, who prefers to paint on a large canvas. Washington Black is Edugyan’s third novel and her second to be shortlisted for the Booker Prize after Half Blood Blues. Building on the dialogue opened up by Nigerian American writer Teju Cole, Edugyan centres her story on the White Saviour Industrial Complex, a term that Teju Cole coined. Among other things, the White Saviour Industrial Complex sees the white saviour ‘supporting brutal policies in the morning, founding charities in the afternoon, and receiving awards in the evening. The world, for the white saviour, is nothing but a problem to be solved with enthusiasm.’

These are precisely the things that the white saviour in Washington Black does.

Washington Black is the story of a slave in a Barbados plantation in the nineteenth century who is whisked away to apparent freedom by a white inventor in a flying balloon. Later, abandoned by his rescuer, the struggle of the runaway slave to build a life in a white man’s world forms the plot of novel. A novel on race can scarcely escape the legacy of Ralph Ellison and his seminal work Invisible Man and Edugyan pays her due homage too. As the black slave tells his one-time white saviour ‘you did not look at me and see me. You wanted to, but you failed. You saw in the end what every other white man saw when he looked at me.’

Despite its complex and sensitive theme, Washington Black is a delightful read, and that is what makes Edugyan’s craft special. The breeziness of the plot, however, becomes its weakness too, at times appearing too flimsy. Far too many coincidences and fortuitous circumstances egg our hero onward to his destination. For instance, when the flying balloon in which our heroes escape the slave plantation crashes onto a ship in the Atlantic, the captain barely bats an eyelid, as if men in hot-air balloons crashing into ships was commonplace in the early nineteenth century.

The Milkman – Anna Burns

‘The day Somebody McSomebody put a gun to my breast and called me a cat and threatened to shoot me was the same day the milkman died.’

Thus begins the most remarkably original novel on this year’s shortlist. It doesn’t let the reader go until the very end.

Set during an unnamed conflict in an unnamed country – though we soon know that the country is Northern Ireland and the time is that of the Irish Troubles – Anna Burns takes a scalpel to the moral economy of a society torn by political conflict and deftly pulls back layers to reveal what violence does to society, and particularly to women, demonstrating how women and their bodies become the battleground for a larger game.

Burns brings together an unforgettable cast of characters not unlike Joseph Heller’s Catch-22. People don’t have names, they’re identified by the things they do or how they appear to others.

There’s Tablets Girl who goes around dropping poison pills into peoples’ drinks; Nuclear Boy who talks of nothing but a nuclear holocaust; Milkman, then a real Milkman; Pious Women, who later become ex-pious women after they begin to desire a man; there’s maybe boyfriend who later becomes ex-maybe boyfriend and so on.

The protagonist, unnamed like everybody else in the novel, is a young girl in her late teens who sees her life turned upside down one day when rumour begins to float in her paramilitary controlled neighbourhood of her alleged liaisons with a militant. As things enter a whirlpool of fate, history, and human frailty, it soon becomes impossible, and futile to separate the truth from hearsay. The one man who she can count on is her brother-in-law, who doesn’t believe in the rumours floating around about her. However, his reasons for not believing her remind the contemporary reader eerily of the non-physical sexual harassment that has been the focus of the #metoo movement.

‘It was simply that brother-in-law would be incapable of believing that anything that wasn’t physical between two people could in fact be going on. So how would I open my mouth and threaten widespread disintegration of the current status?’

The Milkman is an extraordinary novel, and in my opinion the one book that deserves to win the Booker Prize this year.

The Mars Room – Rachel Kushner

Rachel Kushner is the second American on the list this year. She is the author of The Flamethrowers, which was a finalist for the 2013 National Book Award.

The Mars Room is the story of a stripper, who is sentenced to serve multiple life-terms in a California prison, leaving her seven-year-old son behind. In this meticulously researched novel about the poor and especially about poor women in America, Kushner gives the reader a guilty peek into the world of those who fell through the cracks of American society with little hope of redemption – the forgotten and the damned of a successful capitalist society.

Kushner is innovative and presents to the reader more than just a gritty tale of crime and suffering. In her depiction of sexuality for instance, Kushner achieves a successful reversing of the gaze as we see male characters thinking of their own genitals, much the way male writers have traditionally described female bodies. In doing so, Kushner gives a passing wink to the Describe Yourself Like a Male Author movement that started last year on Twitter when women writers questioned the inability of male writers to describe female characters without overtly sexualised references to their bodies.

The jarring issue with The Mars Room, however, is that though a brilliant read and an emotional roller coaster ride, it feels a little faded from use. The cast that Kushner conjures up of train-wrecked lives, drug addicts, hookers, corrupt cops, and street-smart toughies feels familiar through having been the staple of American cinema, literature and music for nearly half a century now. There is a long legacy of literary fiction that has given us these same people and their lives – Tibor Fischer, Richard Price, Tom Wolfe, Hunter S Thompson, Irvine Welsh, to name a few. We’ve also seen these stories come alive on cinema, and we’ve heard about the lives of these people in rock music of the 1970s and hip-hop of the 2000s. With Netflix having stepped up the content wars, we’ve even got a detailed glimpse of an all woman prison and the lives of its inmates through series such as Orange Is the New Black, and it is still fresh in our minds.

Matters aren’t helped either by Kushner’s use of societal and cultural cliches for her characters like those around ‘Americans discovering countries only after bombing them’. It might be true. But it’s been done to death.

From an Indian reader’s perspective there’s the additional element of relativity of suffering – being poor in America isn’t the same kind of suffering as being poor in the Third World. An abandoned child does not go into a state system, to be taken care of raised by the state. That would be a luxury. The child is simply left to fend for herself on the street or die. Jail inmates do not get shampoo, conditioners and soda cans nor do women who work the streets drive cars. Thus while the world that Kushner creates might appear stark to a reader in America or Europe, in India where a middle class professional earns less than the American minimum wage, and where roughly half of the world’s poorest live, it simply fails to have the desired effect. Being poor and in jail in America is hard. But it’s nothing compared to being poor and in jail in the Third World.

Everything Under – Daisy Johnson

At 28, Daisy Johnson is by far the youngest author on the list. Everything Under, her debut novel is a delightful reworking of the ancient tale of Oedipus intertwined with a lovingly crafted story about the bond between a mother and a daughter. The mother in the story, Sarah, is a tough-as-nails, carefree woman who lives on her own boat and catches fish from the river to survive, watching the sun go down with a cigarette dangling between her lips, a glass of brandy in hand, from the deck of her boat. She takes love wherever she can find it and expects little in return. From one such liaison, her daughter Gretel is born. Not one to be tied down to things for long, Sarah eventually floats away, leaving Gretel in foster care, painfully trying to build a bridge between the impossibly secluded world she shared with her mother on the boat, and the world of real people, of schools, university and jobs that follows.

Like in several other novels on the shortlist, gender fluidity is an important theme Johnson explores through one of the transgender characters. However, the magic of Everything Under lies in the delicate skill with which Johnson creates the raw, isolated world of a mother-daughter surviving in a forgotten nook of society, where even the police do not come to enquire after the dead. Left to themselves, away from all the institutions that define society, they create their own endearing private language – words like ‘DuvDuv’ or ‘Bonak’, that mean nothing in the real world but which for the abandoned daughter, become a reminder of the painful process of forgetting and relearning as she slowly settles into the real world after her mother leaves her. She finds a real job, working, among all things as a lexicographer – or a person who compiles dictionaries – and sets out to delve into the many beginnings of her past that never found their endings.

Everything Under is masterfully told, and despite its grim setting, never bogs the reader down. At a little over 200 pages, it also delightfully bucks the trend of doorstopper novels that have of late become the norm in literary awards. There is also the little matter of records trivia – in case Daisy Johnson wins the Booker, and this writer is certainly rooting for her to, she would tie for the youngest writer to ever win the Booker along with the 2013 winner Eleanor Catton who too was 28 when she won.

The Long Take – Robin Robertson

Robin Robertson is a Scottish poet, who is considered among the greatest lyrical voices of our times. The Long Take, though structured like a novel, is composed in a mixture of verse and prose, defying form and classification. Like Richard Powers in the list, Robertson has tried a great literary experiment. Unlike Powers however, Roberstson succeeds spectacularly.

The Long Take is the story of a battle scarred world war veteran who wanders through America, haunted by his past.

‘People; just like him.

Having given up the country for the city,

Boredom for fear, the faces

Gather here in these streets

Like spectators in a dream.

They wanted to be anonymous

Not swallowed whole, not to disappear.’

The Long Take was a surprise entry in the shortlist this year. It is, however, a sign that the Booker judges are open to accepting newer, innovative literary forms. Earlier, a graphic novel too had made it to the longlist.

The Long Take is more a narrative poem in the tradition of the epic Greek poems than a novel. It is like poems a thing of beauty.

‘The subways are rivers, underground,

Flash flooding every five minutes

In a pulse of people.’

It wouldn’t be surprising if Robertson were to win. On merit alone, Robertson, along with Anna Burns remain the favourites. However, the Booker Prizes have come under criticism of late for their arbitrary choices often based on criteria unrelated to literary achievement. While the shortlist may not necessarily represent the best literature in the English language produced this year, it is certainly among the best.