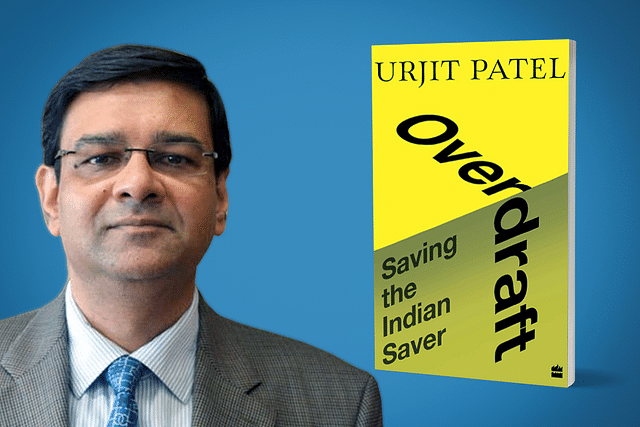

Overdraft: Urjit Patel Has Left A Lot Unexplained In His Hastily Written Book

In his book, Overdraft: Saving the Indian Saver, Urjit Patel has dashed expectations.

One cannot escape the impression the book was hastily put together.

Urjit Patel. Overdraft: Saving the Indian Saver. Harper India. 2020. 248 Pages. Rs 373

In Overdraft: Saving the Indian Saver, a compilation of his speeches and articles, former Reserve Bank of India (RBI) governor Urjit Patel explores the roots of our banking crisis, narrates the measures the RBI took to address it and describes how for a variety of reasons these measures have only met with partial success.

The banking crisis, Patel points out, has its origins in unrestrained credit expansion undertaken by the central government to fuel economic growth.

As government owns a large part of the banking system and as its fiscal headroom is limited, it uses public sector banks (PSBs which Patel calls GBs or government-owned banks) to pump-prime and stimulate the economy — a process Patel calls fiscalisation of the banking sector.

Reckless lending combined with inadequate or misdirected incentives, poor risk-management processes in banks, delayed regulatory responses, regulatory forbearance, the growth euphoria which drowned out voices counselling circumspection and a marked propensity among businesses in India to use debt as opposed to equity to finance their businesses and to game the system combined to bring the banking system to its knees.

It should hardly come as a surprise that PSBs have borne the brunt of the crisis. The binge had to end and when it did no one came out smelling of roses.

Patel points out how the crisis has stalled credit to credit-worthy borrowers as well as raised the cost of borrowing and weakened the interest rate transmission mechanism, to the overall detriment of the economy.

All of this is well known and Patel covers familiar ground. While government's propensity to open the tap is well known, what of the RBI, the banking regulator?

Patel does not shy away from casting a critical eye on the central bank he helmed for two years. He describes the RBI as a 'soft regulator” and points to its inadequate assessments of sector risk and consequent failure to tighten norms in time.

The RBI did not challenge banks' assumptions nor insist on their being stress-tested. Most egregious of all, the central bank permitted the evergreening of bad loans (a win-win for both lender and borrower) and relaxed banks' exposure norms to the highly risk-prone NBFC (non-banking financial companies) sector.

While commending the RBI's professional, integrity he also says they may have been "looking behind their shoulders" at times.

Such candour from a central bank governor is refreshing but one wishes he had also dealt with the issue of RBI’s accountability for the crisis in its capacity of supervisor and regulator of the banks.

Like other central bankers, Patel wants central bank autonomy and for good reason. But independence without accountability is a recipe for irresponsibility.

Does the RBI not suffer from the same lack of accountability which Patel bemoans in government-owned banks?

Enough information is routinely available in the public domain about sectoral performance as well as about the financial position of individual borrowers, especially the large ones. Therefore Patel’s blaming "asymmetry of information..." to exonerate the RBI does not wash.

There is no doubt the central bank slept at the wheel and for too long. And no heads have rolled at Mint Street.

When the RBI woke up to the challenge, it enacted a slew of measures aimed at recognising and reporting bad loans early through an asset quality review (AQR), prohibiting evergreening, encouraging timely restructuring of accounts considered viable and recovery and sale of unviable ones.

In fact, it was the AQR which laid bare the magnitude of the crisis.

A central repository of information on large credits made available real-time data on large exposures by lender and by borrower.

The Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC) was government's contribution to this exercise.

But the RBI's (in)famous circular of February 2018 sent shock waves through the system.

Superseding previous circulars, this one mandated that banks prepare a resolution plan for all large accounts within 180 days of a default by a borrower by even a single day, failing which the borrower was to be taken to bankruptcy under the IBC.

Patel points out how this and other measures were stymied by vested interests, the courts and the government from being given full play.

The result — partially implemented solutions, festering problems, unconscionable delays in resolution of distressed assets, fragile bank balance sheets and an economy shackled and moribund for want of credit.

Government bowed to pressure from business and allowed itself to be persuaded that the central bank's pill was too bitter to swallow. It has also gone about diluting the IBC which it itself had enacted with much fanfare.

By striking down the RBI's February 2018 circular on the ground that it fell afoul of the Banking Regulation Act, the Supreme Court contributed its bit too — speaking of which Patel writes poignantly that "lawyers who had agreed to represent RBI in the Supreme Court dropped out at the eleventh hour, literally the night before the hearing".

Did the government play a hand?

The SC was to later strike down a mandatory time period for resolution under the IBC declaring speciously and with twisted logic that any such deadline was inconsistent with Article 14 of the Constitution!

The only beneficiaries have been fat-cat borrowers, who with the help of moneyed lawyers and friends in high places continue to cream and game the system and get away scot-free.

As if these were not enough, Patel notes that the RBI under his successor has been only too ready to bend to the diktats of the government.

Although the SC did not rule against the one day default rule introduced by the impugned February 2018 circular, the RBI provided a 30-day window via its June 2019 circular, and what is more has refrained from directing banks on a case-by-case which was what the Banking Regulation Act required and which the impugned February 2018 circular did not provide for.

He also criticises the inclusion of NBFCs under the ambit and scope of the IBC and government's efforts to undermine the IBC by calling on lenders and borrowers to settle outside of it.

Patel warns that unless regulators and the government stay the course in cleaning up the mess, the consequences will be severe.

Kicking the can down the road will only exacerbate crises, not resolve them.

Given that PSBs are not going to be privatised in a hurry and fiscal space will always be limited, and absent the salutary restraints applied by market discipline, the only way to keep government owned entities on the straight and narrow, and ensure they do not cause economic harm is through tight regulation.

Unfortunately, as Patel shows the RBI is hamstrung by the Banking Regulation Act in its efforts to regulate the PSBs.

One wishes that Patel had gone further to consider how the leveraging of borrowers' balance sheets can be prevented – can debt be made less attractive by doing away with the tax-deductibility of interest?

Will threshold equity requirements for various kinds of borrowing as well as on the borrower as a whole ensure that borrowers have a skin in the game?

Speaking of skin in the game, how does one ensure the RBI has one too?

Given the important role it plays in supervising and regulating the banking sector, should not the RBI’s explicit mandate go beyond inflation targeting?

Or, should the supervisory and regulatory function be removed from the RBI and handed over to a separate banking regulator?

Also given the debate around the transfer of RBI's surpluses to government which raged when he was governor, it would have been interesting to learn of his views in the matter.

Alas this is not to be.

As an economist and former central banker, what are Patel’s recommendations to restore economic growth post Covid-19? We do not know.

One also hopes Patel's next book is better written. If banks' balance sheets are stressed, Patel's language is strained and is hardly a model of clarity; the grammar is often faulty. No fewer than 74 acronyms distract the reader in a book of 180 odd pages. One cannot escape the impression the book was hastily put together.

Sankar Ramamurthy is a chartered accountant and retired corporate executive.