A Secret Note By R&AW Chief R N Kao In 1971 Warned About Pakistan Launching An Attack Against India

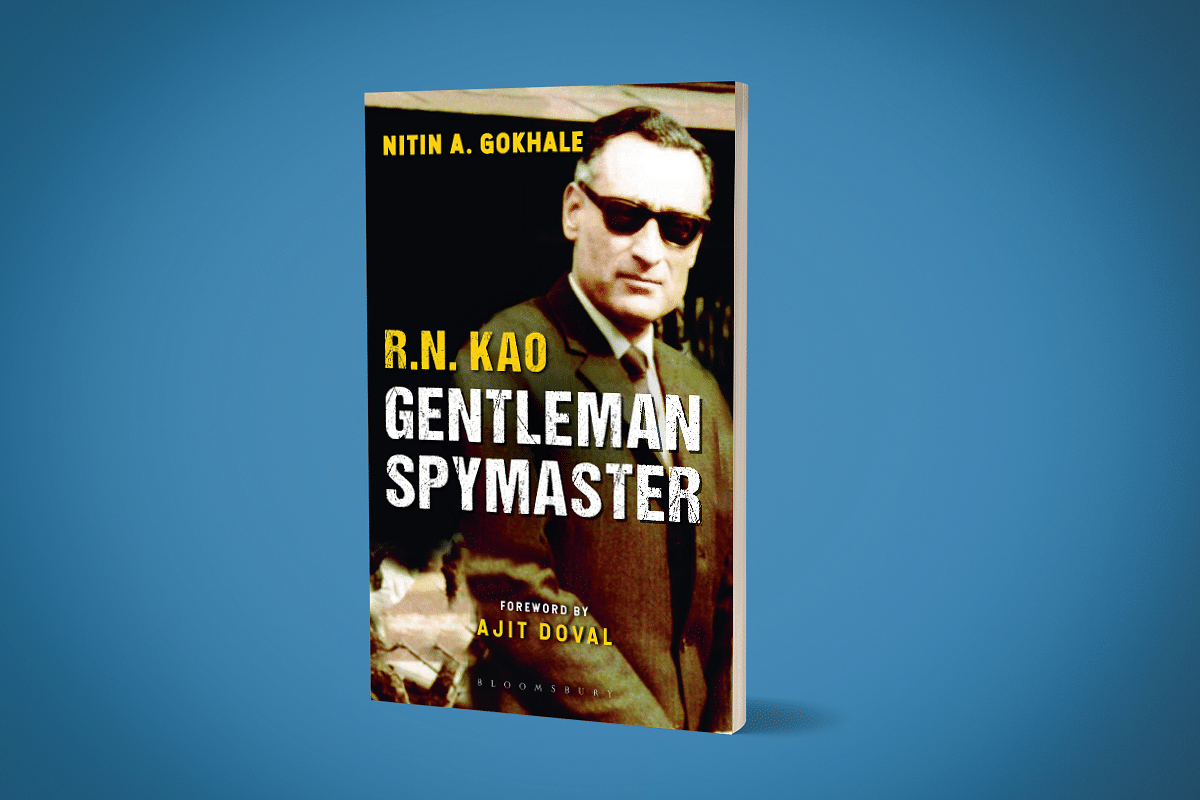

In January 1971, R&AW chief R N Kao wrote a note to then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi detailing the political climate in India, Pakistan and East Pakistan. And subsequently, Bangladesh was born through a series of events. Here’s a glimpse of the man behind the entire story through Nitin Gokhale’s book ‘R N Kao: The Gentleman Spymaster’.

India was watching the events unfolding in Pakistan closely. The R&AW, tasked with foreign intelligence, was keeping a wary eye on India’s neighbour. In a 25-page secret note dated 14 January 1971 (two days after Yahya had landed in Dhaka), addressed to the Cabinet Secretary (with a copy to P.N. Haksar), RNK warned of the possibility of Pakistan launching a military campaign against India to divert attention.

He went on to elaborate, ‘After the recent elections, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman has emerged as the unchallenged leader of East Pakistan… He would, therefore, be in a strong position to press for the incorporation of his party’s six-point programme in the Constitution. He would find it difficult to make any compromise in his stand on the main Constitutional issues, since his party had declared that the elections would be considered as a referendum on the six-point programme.’

The R&AW note pointed out that ‘In the Western Wing of Pakistan, particularly the Punjab and Sindh [Zulfikar Ali], Bhutto seems to have captured the imagination of the common man, because of his promises of early radical changes in the social and economic order… It is difficult to judge whether his anti-India posture yielded him rich dividends, because other rightist parties, the leaders of which also consistently indulged in India-baiting, did badly in the elections.’

In RNK’s assessment, the peculiar situation that had emerged in Pakistan after the election results presented a big dilemma for President Yahya Khan.

He noted, ‘The present ruling elite consisting of hard-liners in the armed forces, the privileged bureaucrats and the vested economic and federal interests might possibly exert pressure on Yahya Khan to try to reserve the trend towards the transfer of power to the representatives of the people in the circumstances which have emerged from the elections. In that event, there would be a temptation for Yahya Khan to consider the prospects of embarking on a military venture against India with a view to diverting the attention of the people from the internal political problems and justifying the continuance of the Martial Law.’

The situation in Pakistan remained fluid and Yahya was trying to find a political solution through a compromise between Mujib and Bhutto. However, RNK, whose job was to look at the worst-case scenarios, concluded, ‘[The] present political situation in Pakistan has not crystallised and is at a very crucial stage. The success or failure of the current Constitutional experiment could be expected to have a definite impact on Pakistan’s policy towards India. If the present Martial Law regime sincerely desires to bring about political stability in the country and pacify the alienated East Pakistani with a view to keeping the two Wings together, it would avoid a military show down with India. The threat of a military attack or infiltration campaign by Pakistan would also recede if genuine democracy starts functioning in Pakistan. There would, however, be the increased possibility of Pakistan resorting to a military venture against India if the democratic process is aborted or the National Assembly is dissolved either due to its failure to evolve an agreed Constitution or refusal by Yahya Khan to authenticate it.’

The R&AW note had also estimated the Pakistani military strength at that point in time and had concluded, ‘Pakistan has considerably increased her armed strength since 1965. Her Army, Navy and Air Force have achieved a good state of military preparedness for any confrontation with India. The potential threat of a military attack by Pakistan on India is quite real, particularly in view of the Sino-Pakistan collusion. Pakistan has also the capability of launching another infiltration campaign into Jammu & Kashmir.’

The note concluded that the Sino-Pakistan collusion was on the rise but correctly predicted — as it was proved in December 1971 — that in the event of a military conflict between India and Pakistan, China will not directly intervene but will support Pakistan morally and materially.

‘The relations between China and Pakistan continue to be close… However, while there have been clear indications of collusion between China and Pakistan in pursuing an antagonistic policy towards India, there is little evidence so far to show that these two countries are planning a concerted military action against India… It is unlikely that China would actively get involved, militarily, in Indo-Pakistan conflict. Nevertheless, it is to be expected that in the event of all-out hostilities between India and Pakistan, China would adopt a threatening posture on the Sino-Indian border and even stage some border incidents and clashes, to prevent the diversion of Indian troops, assigned to meet the Chinese threat, to the theatres of war with Pakistan. China would also assist Pakistan by arranging a steady flow of supplies and military stores.’

The R&AW had assessed that Pakistan had persistently procured military hardware from all available sources. This hardware had been utilised to build the strength and equipment of Pakistani armed forces and the stockpile of reserves.

The US had also offered to sell to Pakistan 300 armoured personnel carriers, seven B-57 bombers, six F-104 star fighters and four P-3 Orion long-range maritime reconnaissance aircraft.

Pakistan and France had concluded negotiations on procuring 24 Mirage III E and 30 Mirage V aircraft over the next two-three years, the R&AW informed Prime Minister Indira Gandhi.

India, on the other hand, was erratic in modernising its military after the 1965 war.

RNK’s note pointed towards Pakistan’s likely attempts to increase infiltration of small groups of armed and well-trained personnel into J&K.

‘The main targets of the infiltrators would be bridges, lines of communication, petrol and supply dumps, airfields, formations headquarters, ammunition depots, police stations, power houses and other key installations. It would appear to be the current strategy of Pakistan to work towards building up popular unrest in J&K, which could be exploited at an opportune moment for launching a “liberation movement” there,’ the assessment concluded.

Meanwhile, as East Pakistan careened towards an unprecedented crisis, Indian decision makers were already making contingency plans. Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, despite her preoccupation with the upcoming elections, found time to be briefed regularly on the developing situation in East Pakistan. Haksar, her sounding board and principal trouble-shooter, along with RNK, was worried about the fallout of the internal trouble in Pakistan.

Hence, based on RNK’s 14 January 1971 note about Pakistan’s attempts to strengthen its armed forces and create trouble in J&K, Haksar sent a telegram to India’s Ambassador to Moscow, detailing the military equipment that India needed urgently to be ready to face any Pakistani aggression.

The list included tanks, APCs, guns, ammunition, bomber aircraft, surface-to-air guided weapons and aircraft for India’s aircraft carrier. ‘We have no, repeat, no other source of supply than to rely upon Soviet readiness to understand and respond to our needs,’ Haksar’s telegram, quoted by Jairam Ramesh in his 2018 book, said.

Simultaneously, Haksar sought and secured Indira Gandhi’s permission to set up a 5-member committee (Committee on East Pakistan), including himself and Kao, under the Cabinet Secretary’s chairmanship. It included, the Home Secretary and the Foreign Secretary in the beginning. The committee was formed to figure out ways to respond to the evolving situation in East Pakistan.

The work was to be coordinated by RNK as the member secretary showing the importance which he had in the government structure at that point in time.