Urban Naxals: A Book That Exposes The ‘Breaking India’ Campaign

Urban Naxals is an attempt to understand and portray the reasons why those who call themselves ‘intellectuals’ are always seen as being apologists for India.

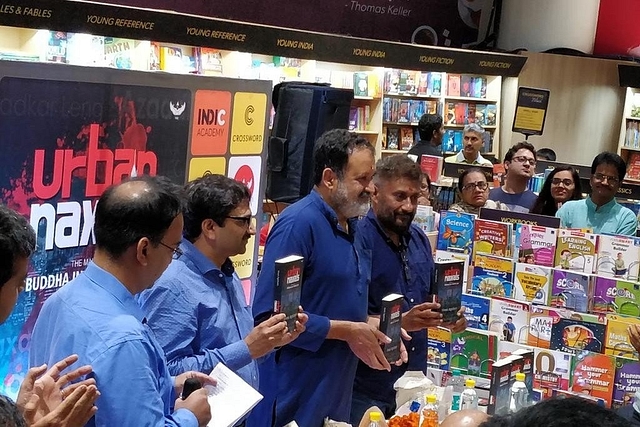

There are those who promote Make in India for the welfare of the country, and there are others who talk of breaking India. Yes, the invaders left us in 1947, but their ‘Macaulayan’, or rather Machiavellian mission remains thoroughly alive. Urban Naxals, a book written by Vivek Agnihotri, who directed the award-winning film Buddha in a traffic jam, sets out to expose this very sinister design whose chief architects comprise the jihadists, the Maoists, and the evangelicals – all three representative of absolutist forces that seem to have one trait in common - jealousy over Indic growth and civilisation. The book was launched in Bengaluru on Sunday (17 June) at Crossword book store in Mantri Mall, Malleswaram.

Mohandas Pai, formerly chief financial officer of Infosys, and now venture capitalist, released the book on the occasion.

The work, which is based on the film thus mentioned, is an attempt to understand and portray the reasons why those who call themselves ‘intellectuals’ are always seen as being apologists for India. Pai also expressed surprise as to how these forces could call themselves ‘intellectual’ especially when India was a land where the culture of anviksiki or inquiry has been staple since time immemorial. Surely, calling these people ‘intellectuals’ is an insult to our rishis by whose grace the nature of the soul (believed to transcend the intellect) was revealed millennia ago, he said.

Pai, in a stinging observation, said that when marauders come to conquer another civilisation, the first thing they do is to destroy its centres of learning. And Nalanda, he said, was a strong case in point. A renowned centre for learning in the region now called Bihar, Nalanda was destroyed by Bakhtiar Khilji, the military general of Qutbuddin Aibak, an Afghan ruler who invaded India in the twelfth century.

It is the same modus operandi that today’s anti-India forces use to destroy the country, albeit in a more sophisticated way, says Agnihotri’s book. It works by co-opting the intelligentsia (which comprises elements in the media, academia, non-governmental organisations and government) into its destructive game-plan.

Another method employed by these forces is one that was used by Thomas Babington Macaulay, or ‘Lord’ Macaulay as the British called him. Macaulay divided the world into civilised nations and barbarism, with Britain representing the ‘highest’ point of civilisation. From this very idea of supremacy flowed his idea of ‘Indian inferiority’. As an agent of the Raj, he was tasked with finding suitable ways to subjugate Indians. However, when confronted by a rich wall of civilisation and culture, he found that the only way he could break it was to crush the Indian’s sense of pride in his identity. Thus was born his famous Minutes on education or what they call Macaulay’s Minutes.

It is no wonder then that every attempt is made to denigrate concepts that are Indian, and glorify anything that is otherwise. Another narrative that these forces shove down our throats, Agnihotri says, is ‘lack of freedom’ in the country. Now, anyone with a sane sense of Indian history, philosophy or culture, will attest to the immense freedom its literature and Constitution bestow upon its citizens. The freedoms enshrined therein are well thought out, keeping the best interests of man in mind. In this context, it is important to highlight the space given to the materialists or Carvakas in ancient Indian philosophical discourse, thus proving the case for real secularism of thought.

Efforts are also being made to destroy the basic unit of family, the filmmaker says, and this is being done through a systematic process of warped Anglicisation. It is not surprising then that when a government formed by a party that publicly asserts its right to national pride, is lawfully elected by the people, allegations of fascism and totalitarianism are levelled to discredit it.

Agnihotri’s film begins with a scene in a village where its hapless residents are sandwiched between greedy politicians on the one hand and oppressive Naxals on the other. What appears in the first few minutes of the movie is the absolute lack of elbow room the common man experiences when opposing forces jostle with each other to grab power.

The work also attempts to highlight how communists present poverty as a virtue to retain control over gullible minds. Any attempt to truly empower the poor, financially, is met with disdain, as it threatens their very formula for political success, reveals the film.

In his concluding remarks, Pai debunked the current communal-secular narrative, saying, “Who is communal and who is secular is very clear, if one applies one’s mind. Ancient Indian metaphysics wholeheartedly endorses the worship of god, both in personal and impersonal ways. We have concepts such as avatara or ‘divine instantiation’, as well as Nirguna Brahman. But to those who believe that only their method of worship is right, or only their god is true, now stand exposed. That, on the contrary, is communal.”

Buddha in a traffic jam did not premiere in the theatres owing to heavy institutional opposition to the film. It is, however, available online. The author-cum-filmmaker has been constantly receiving threats from various quarters for his expose.

(The writer is a copy editor with Swarajya)