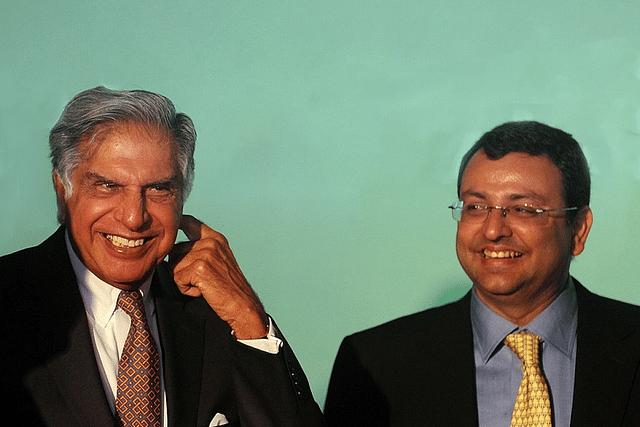

Tough Divorce: Both Tata And Mistry Will Have To Seek A Messy Middle Ground On Valuations

The divorce can be as messy and acrimonious as the events that followed the ouster of Cyrus Mistry in October 2016 from the Tata Sons board.

It had to happen. After four years of bitter acrimony and courtroom battles, the Tata and the Pallonji Mistry groups seem to be on the same page about their future: a divorce.

The Tata Group, which spiked a Mistry plan to pledge Tata Sons shares through a court order, offered to buy out the Mistrys’ 18.4 per cent stake in the holding company, Tata Sons; the Mistrys, after defaulting on payment obligations to group company Sterling & Wilson, have now expressed a willingness to exit Tata Sons if a “fair” deal is offered.

However, let me make a prediction: a “fair” deal is not going to be what the Mistrys want or what the Tatas are currently willing to offer. It will have to be somewhere in-between. The fair deal will actually have to be negotiated by the two groups, and will not depend on what the share valuers say must be paid to Mistry.

The gap is so wide – the Mistry valuation is said to be three times as much as what the last Tata internal valuation indicated – that the much-desired divorce will be expensive for both parties. For the Tatas, it will be expensive in terms of the price they have to pay to get the Mistrys out of their hair; for the Mistrys, they will have to forgo some of the underlying value of Tata Sons shares in order to get anywhere near the cash.

At the last valuation exercise in 2016, Tata Sons was valued at around Rs 3.14 lakh crore; the Mistrys put the value at a massive Rs 9.7 lakh crore today. Their 18.4 per cent stake should thus fetch anywhere between Rs 57,600 crore (the Tata valuation) and Rs 1.78 lakh crore (the Mistry fantasy). Neither are the Tatas going to gift the Mistrys $25 billion in one go nor are the Mistrys going to accept the $8 billion that the Tatas may be willing to offer at some point, and that too with lots of caveats. It may not all be cash.

The reason why the Tatas will not offer anywhere near what the Mistrys want is simple: they hold all the high cards right now, and they can’t donate that kind of money to anybody, leave alone an embittered partner who now wants out. It is the Mistrys that need the cash urgently, and the Tatas can wait awhile to pay them, now that the Supreme Court has refused to allow the Mistrys to pledge their Tata Sons shares to raise money.

Moreover, valuations in an unlisted holding company, no matter how many blue chip stakes it holds in its kitty, will always be lower than the sum of the parts. Tata Sons, despite sitting on a gold mine like Tata Consultancy Services, has incomes derived mostly from dividends. It also has debts raised from share pledges.

Putting it differently, the divorce can be as messy and acrimonious as the events that followed the ouster of Cyrus Mistry in October 2016 from the Tata Sons board. Any settlement will need third parties and many behind-the-scenes negotiations to sort things out. It will probably have to be a mix of cash payments, possibly a Tata Sons listing, or additional payments in kind (ie, handover of some of the shares owned by Tata Sons).

What the impending Tata Son-Pallonji Mistry divorce tells us is this: far-sighted businessmen tend to make elementary mistakes in the handover of power to either inheritors or professionals.

Dhirubhai Ambani left his massive business to his sons to run cooperatively, but he did not leave a will. Thus, his sons had to fight over their inheritance, washing dirty linen repeatedly in public.

Even as we speak, the Murugappa group has declined to give a board seat to the women inheritors of the late patriarch, M V Murugappan, who hold Just over 8 per cent in the holding company, Ambadi Investments. This battle too seems headed for the courts.

One reason for this is that business families not only tend to be patriarchal, but also socialist, where control shares tend to get distributed not according to ability, but equality of inheritance between male siblings. Businesses operate in a competitive capitalist space, but the families that own them tend to see all siblings as equal after the first one or two generations. This is why they either don’t leave a will out of sentimental reasons, or apportion control on the basis of equal holdings for all, never mind which inheritor (or outside professional) is best equipped to run the show after the main promoter leaves the scene.

In the case of the Tatas, they had a different problem. They neither had enough heirs nor the requisite shareholdings to control all their companies. The only real thing that ties it all together is the Tata name. Logically, Ratan Tata will have to find another Tata to run the empire, even assuming a professional can do the actual executive job under him.

That, precisely, was the problem with Cyrus Mistry. He was both part-owner and professional, an impossible power combo for the Tatas to ultimately countenance. Then there was the stature of Ratan Tata to contend with. The latter simply could not afford to walk into the sunset after leaving the company in the hands of a non-Tata.

Neither Ratan Tata nor Mistry fully realised the problems they were getting into by entering into an arrangement whereby the largest minority shareholder in Tata Sons was getting into the driver’s seat.

At the same time, the new boss had an effective superboss in Tata. It could not ultimately have worked. The only logical choice was a professional beholden to the Tatas who could do the job without any claims to overlordship of the group on his own.

The choice fell on N Chandrasekharan. He will now have to help get the Mistrys out by pitching in proposals that will be acceptable to both parties.