V G Siddhartha Tragedy: Lessons To Learn For India Inc And Modi Government

When times are tough, you tighten your belt. This applies to the government too, and not just banks and businessmen.

This is the time to give beleaguered businessmen the long rope and not tighten the noose. A tax noose flung around businessmen will kill any possibility of an early economic recovery.

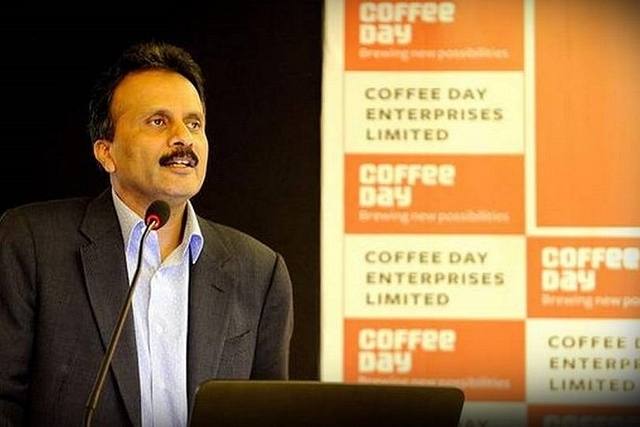

It would be absurd to link the likely suicide of Cafe Coffee Day (CCD) founder V G Siddhartha to the pressures he may have faced from the taxman. His body was fished out of Netravati river near Mangaluru this morning (31 July) after he disappeared on Monday night to take a walk on the new bridge over the river, leaving his driver flummoxed and worried.

Before taking his last dive into the river, Siddhartha is reported to have admitted, in a letter purportedly written to the CCD board and stakeholders, to business failure. He talked of pressure from lenders, private equity players and the taxman – pressures he probably succumbed to.

The truth is that it is the job of the taxman to collect his dues, the equity investor to demand returns on his investment, and lenders to get their money back. If, for some reason, these demands can’t be met from normal business earnings, the logical thing to do is file for bankruptcy before things get out of hand and the pressures become unmanageable.

If you want to blame the taxman, you might as well blame banks or even the Reserve Bank of India for keeping interest rates too high in the current weak business scenario. Or you can even blame Rahul Gandhi for making those clad in suits and boots such objects of popular hate.

But there are lessons to learn from Siddhartha’s tragic business and personal failure. For India Inc, for government, and for political parties in general.

For business, the two most important things to internalise are these: first, the way to grow a business that needs lot of capital is not excess debt. Equity cannot be endlessly substituted with debt. At some point, debt will come back to bite you in the butt, and in the process of avoiding this bite, businessmen will be forced to take chances with the law (delays in remitting workers’ provident fund dues, delays in tax payments and servicing of debts, and adoption of dodgy accounting practices).

This is not to say that Siddhartha did all or any of this, but his letter, assuming it is authentic, does indicate that he was aware of some shortcomings on his part. It said (read the full text here): “I am solely responsible for all mistakes. Every financial transaction is my responsibility. My team, auditors and senior management are totally unaware of all my transactions. The law should hold me and only me accountable, as I have withheld this information from everybody including my family. My intention was never to cheat or mislead anybody, I have failed as an entrepreneur. This is my sincere submission, I hope someday you will understand, forgive and pardon me.” (Italics mine)

The very fact that Siddhartha mentions that there was no intention to cheat or mislead shows that he was aware he was sailing close to the wind.

The second thing to learn is that cronyism will not any more rescue you if your business is failing. This is what the hundreds of businessmen who have been dragged to the bankruptcy courts have discovered, and you have to take your lenders, investors and employees into confidence well before you know you are in deep trouble. This way they at least know you are honest, and can provide the backing needed for revival if it is still possible. Few bankers will refuse to offer an additional loan if it is possible for them to lose less from bankruptcy; and no investor will refuse to back an entrepreneur who knows when he needs money to change course or adopt a better strategy. You can’t build trust with lenders and investors if you cannot tell them the truth early enough, or head for the bankruptcy courts if no legal rescue plan is workable.

Proximity to politicians can be a double-edged sword for businessmen. At times they may be helpful, but if you are seen as too close to one party, the chances are that another party will see you as an enemy. It is worth recalling that raids on Siddhartha’s Cafe Coffee Day premises followed raids on former Karnataka cabinet minister D K Shivakumar two years ago, widely seen as the Congress party’s moneybags in this southern state.

The second lesson is clearly for the government and the taxman, especially the former, to learn. Two lessons, in fact. One is not to get too greedy on tax revenues, and the other is to give India Inc time and space to reform and adjust to the new realities of doing business the clean way.

We need to re-emphasise that there is probably no direct link between the taxman’s demand on Siddhartha and his suicide, but there is now a clear temptation for the government to raise more tax resources from the wealthy and from businesses, since these funds are required for financing the social security schemes of the Narendra Modi government. The increase in taxes for those earning above Rs 2 crore in the recent budget is one indicator; the slow reduction in corporate taxes for bigger companies is another. The move to tax investments in startups (the “angel tax”) on the premise that these may be donations rather than genuine investments – partially corrected in the budget – is yet another indicator. The move to launch the 5G auction this year, never mind how poor the health of the telecom sector seems, is yet another signal indicating the government’s hunger for resources.

When governments demand more in taxes, the taxman will indeed over-reach. Modi may be setting new benchmarks in probity and anti-corruption, but our system if far from benign, and pressure on taxmen to bring in more will – at some point in time – result in the taxman making unreasonable demands on businessmen or the rich. This tendency needs to be nipped in the bud before more taxmen start believing that their job is to keep pushing tax collections up endlessly.

The other point is really sensible economic timing. If the old cronyism is being dismantled, and government-business ties are being reset to ensure more clean working and less corruption, it will take time for businesses to readjust to this new reality. Also, when banks are stuffed with bad loans, and companies overloaded with debt, they will both take time to recover from the financial pressures brought on by the reset in ties with India Inc.

Businessmen cannot overnight change the way they do business, nor will they have the capacity to do so when banks are themselves getting more cautious about who they lend to, and against what kind of liquid collateral. When there is a double balance-sheet problem, and various sectors are in deep trouble (telecom, autos, real estate, banks, aviation, infrastructure, power, steel, you name it), it makes little economic sense to push surviving companies to the brink with high tax demands or intense pressures for tax-compliance.

The truth is Indian rates are high for the average corporation which not only pays taxes, but also various kinds of speed money to meet compliance burdens on other fronts (labour, environment, etc). It is not surprising that last year 5,000 millionaires left the country, possibly to avoid the tentacles of a system built on the principle of extraction.

A simpler point is this: when times are tough, you tighten your belt. This applies to the government too, and not just banks and businessmen.

All things considered, this is the time to give beleaguered businessmen the long rope and not tighten the noose. A tax noose flung around businessmen will kill any possibility of an early economic recovery.