Beauty Of The Untranslatable Word

Exploring the connotations of certain words in every language is an experience few can match.

It was the apparent beauty (and the torture thereof for a translator like me) of the Indian words like Asuya, Matsar,Uddhishta, Nishtha, Maryada, and many such googlies I tried dodging while translating some classics, which made me write this piece.

The word tsundoku in the Ella Frances Sanders book ‘Lost in Translation: An illustrated compendium of untranslatable words from around the world’ made me feel good that I am not alone when I pile up books without reading them. In his book Black Swan, the author Nassim Nicholas Taleb makes a similar argument, quoting Umberto Eco who says, ‘Read books are far less valuable than unread ones’.

The library should contain as much of what you do not know as your financial means, mortgage rates, and the currently tight real-estate market allows you to put there. You will accumulate more knowledge and more books as you grow older, and the growing number of unread books on the shelves will look at you menacingly. Indeed, the more you know, the larger the rows of unread books. Let us call this collection of unread books an antilibrary.’

tsundoku: Japanese for leaving a book unread after buying it, typically piled up together with other unread books.

Each language around the world has umpteen such words. Take the Norwegian word forelsket, which most teenagers would have experienced at least once in their lives. It roughly translates as ‘the indescribable euphoria experienced as you begin to fall in love.’

Once they move from that stage, the lovers might experience what in Tamil is called oodal which translates as ‘the overly exaggerated, fake anger that follows a lovers’ tiff when one person sulks and pouts dramatically after a silly fight to make the other suck up and admit his or her mistake!’

Later, when the girlfriend begins to show some of her traits, a Bengali would describe her as being nyaka. Apparently, it originated from the Persian word nek which means an honest man.

Subsequently, it changed its meaning to imply an excessively good man or a fool. It is most often used to describe women who show a mixture of coyness and coquetry.

The pair of lovers, who have waited at bus stands, parks or any other rendezvous, would appreciate the Inuit word iktsuarpok, which stands for ‘the frustration of waiting for someone to turn up.’

A lot has been about jugaad, some having made a book out of it. While it does not require an explanation for a Hindi speaking person, it has a long-winded and somewhat inappropriate meaning of trying to get something done with minimal resources, and even if that means by hook or crook.

A lot of people would confuse the Hindi word romanch with romance but the closest description is a least known English word ‘Horripilation’ which itself needs translation, and means ‘the erection of hairs on one’s skin due to cold, fear or excitement.’

Tell a person from Kolkata about an adda and he is immediately transported to an image difficult for a non-Bengali to imagine. It is not just a group sitting together and discussing endlessly. Which is the general feeling, but how does one translate adda, if one needs to translate it at all? ‘Chat’ doesn’t adequately describe the fusion of cups of tea and the endless rising of words, providing intellectual stimulus or just noise. The image of college street and coffee house makes someone who has lived there really nostalgic. For others, it is just a word!

I love the usage of ethi in Bihar. It is used as a substitute for anything you are not able to name. ‘Arre, woh ethi le aao,’ says the mason to his assistant, and the other person understands what he wants! It is difficult to describe the expression, unless you have stayed in Bihar.

The most untranslatable Indian word – jootha in Hindi or ushta in Marathi or entho in Bangla is difficult to explain to an English speaking audience as ‘food which has been defiled (for the other person) as it has been touched or partially eaten by the first person, hence making it unfit for anyone else’s consumption.’

When we say kimkartvyavimoodh in Hindi, we are talking of many things together including ‘a state of dilemma due to inability to decide, being at crossroads, etc.’

The idea that words cannot always say everything, has been written about extensively. As Friedrich Nietzsche said:

‘Words are but symbols for the relations of things to one another and to us; nowhere do they touch upon the absolute truth.’

In ‘ Through The Language Glass: Why the world looks different in other languages,’ Deutscher goes a long way to explain these loopholes – the gaps which mean there are leftover words without translations, and concepts that cannot be properly explained across different cultures.

It is very difficult for anyone outside of Germany to appreciate a word Fernweh, which translates to ‘feeling homesick about a place you have never been to!’

The Chinese word yuanfen is a complex concept loosely translated as relationship by fate or destiny, but it draws from the principles of predetermination in Chinese culture, which dictate relationships, encounters and affinities, mostly amongst lovers and friends. It is a sort of a ‘binding force’ linking two individuals.

Here in India, it is easy for someone born with the Indian ethos to understand the word Runanubandha as an existing physical as well as emotional bondage with our contemporaries. Runanubandha is the only known reason to understand the strange and weird encounters that happen in our lives with people who are near and dear to us. It gives us the soothing reply to the sufferings we encounter in life with a readymade answer in the unfolding of the past life debts.

Emperor Charles V, King of Spain and master of many European languages, is supposed to have said that he preferred to speak ‘Spanish to God, Italian to women, French to men and German to my horse.’

In another one of his didactic-sounding but exceptionally readable book titled ‘The Unfolding of Language’, Guy Deutscher talks of a Turkish word Sehirlilestiremediklerimizdensiniz meaning ‘you are one of those whom we cannot turn into a town-dweller.’ The author clarifies that it is not a phrase or words squashed together but is actually just one word. In another place, he talks of a Sumerian word, munintuma’a, meaning ‘when he had made it suitable for her.’

Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote a poem using the German word Waldeinsamkeit, which loosely translates to ‘forest solitude’ but has a far deeper meaning like ‘being alone in the woods, connected to nature’ and has a philosophical angle to it.

In a contest carried out by the Times of UK a couple of years ago, the most untranslatable word was ilunga, from the Bantu language of Tshiluba, spoken in Congo, meaning a person ready to forgive any abuse for the first time, to tolerate it a second time but never a third time. The word next was hlimazl in Yiddish for the chronically unlucky person.

The lengths to which the Russian author Vladimir Nabokov goes to describe the Russian word toska is amazing. He says, ‘No single word in English renders all the shades of toska. At the deepest and most painful level, it is a sensation of great spiritual anguish, often without any specific cause. At less morbid levels, it is a dull ache of the soul, a longing with nothing to long for, a sick pining, a vague restlessness, mental throes, yearning. In particular cases it may be the desire for somebody or something specific, nostalgia, lovesickness. At the lowest level it grades into ennui, boredom.’

The word jayus in Indonesian, means a joke so poorly told and so unfunny that one cannot help but laugh.

Indians seem to have learnt the jugaad to give “missed calls” as ways of sending messages from the Czech and Slovak word prozvonit, which means ‘to call a mobile phone only to have it ring once so that the other person would call back, allowing the caller not to spend money.’

Milan Kundera, author of The Unbearable Lightness of Being, remarked that:

As for the meaning of the Czech word litost, I have looked in vain through other languages for an equivalent, though I find it difficult to imagine how anyone can understand the human soul without it. The closest definition is ‘a state of agony and torment created by the sudden sight of one’s own misery.’

I have faced this problem multiple times, especially bumping into people at airport lounges or at parties and not knowing how to introduce someone as I had forgotten their names. Now I have a Scottish word for it: tartle.

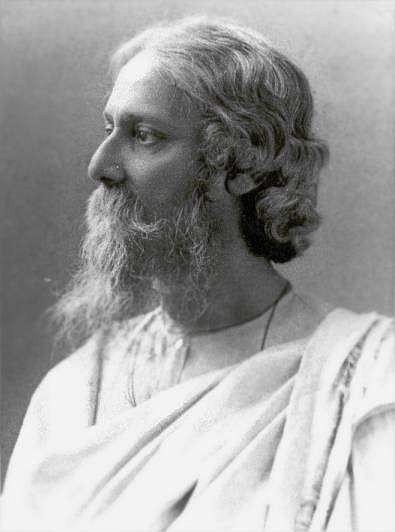

I struggle with innocuously simple sounding words in Hindi like dharma. A word like anushthan has a lengthy explanation meaning ‘performance of certain ceremonies in propitiation of a god.’ When Tagore uses the word abhimaan, he is talking of ‘a sense of hurt pride the female protagonist exhibits.’

I stumbled across what is commonly referred to as the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis, which proposes that the structure and vocabulary that makes up a language reflects the mentality and thought process of the people who speak that language. So, according to the hypothesis, the fact that the word esperar in Spanish serves for the concepts of wait, hope and expectation, would infer something about the Spanish mentality, and implies that those three concepts (which are very different in the mind of an English speaker) are somehow much more similar for a Spanish speaker.

We understand the word sankoch, used in many Indian languages, as not just ‘hesitation,’ which is the literal meaning, but as something wherein ‘the person experiences a sense of embarrassment having received something very extraordinary or unexpectedly and that which the person finds difficult to reciprocate and hence the feeling of sankoch while taking it.’

There is an unending debate on whether a language, and hence the words therein, reflect the culture and the society of the geography they emerge from. Or is such trivia as the number of words for snow or shearing camels something to be ignored? Does different usage of words in a language lead to different thoughts and perceptions? The English and French would endlessly argue on which language has words which help to express better!

In India, one would have Sankrit pundits, willing to stake, a claim that their language was the most scientific but the Urdu speaking elite would stand up to say that no other language is more articulate and that a single beautiful word or a phrase in Urdu can describe a whole range of emotions no one other language can.

We shall debate the superiority of languages, if there exists such a thing, some other day. For me, the very essence of the diversity of words and its meanings in different languages is food for thought.

Enjoy the buffet!