What if Gandhi hadn’t been thrown off the train?

We begin a weekly series on the great imponderables of history. What would have happened if something hadn’t. Enjoy, discuss, scratch your head, argue.

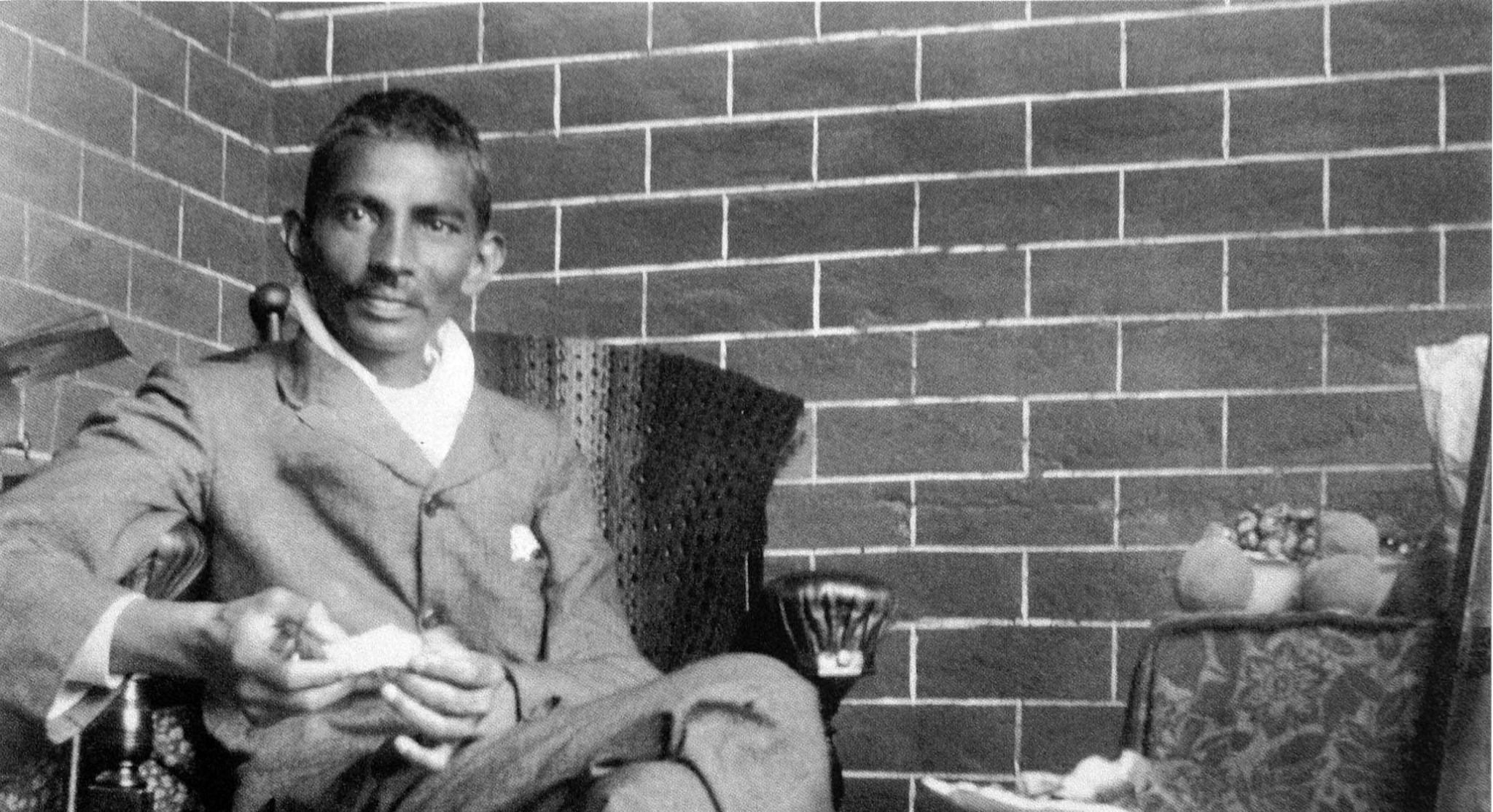

On June 7th, 1893, at a little station called Pietermaritzburg, Mohandas Gandhi was thrown off the train. His baggage was thrown off separately. This was a big mistake. For over 25 years, he was a thorough nuisance to the South African regime. He avoided violence. He talked of virtue. He made them gifts. He refused to play fair. They were very relieved when he left for India in 1915. His parting gift to Prime Minister Jan Smuts was a pair of slippers, which he had made himself.

But what if this had never happened.

Supposing his fellow passenger had said, ‘Hullo, you look quite decent for a brown chap. Fancy a spot of tea?’

Gandhi was not a born revolutionary. He was conservative by nature. His family had hoped that he would earn some money and experience in South Africa, and then come back and take over from his father as the Dewan of Porbander. Perhaps that’s what he would have done, and remained a lifelong loyal servant of the Empire, and built Porbander into a model state, with good roads, full adult literacy, clean toilets, and many goats. Life would have been happy there. Once India became independent, they would have become an example for the rest of us.

But was Gandhi not the engine of the freedom struggle? Without him, would we be free? We probably would, because the British were running out of things to steal. They could have kept us as a captive market for their products, but unfortunately they had already taken all our money, so we were not in a position to buy anything. So there were reasons for them to leave.

Nevertheless, if you visit any Governor’s house anywhere in the country, you can see why they might want to stay. Check out the chandeliers and the sofas, and the number of salutes. Who would want to leave such comfort, unless someone broke in through the window and set fire to the curtains?

So we would definitely have needed the freedom struggle. Who could have led us to freedom? Would it have been Nehru, or Bose, or Patel? Or even Jinnah? We could empty a bar discussing that one, but still, let’s give it a shot.

At first glance, it looks like Nehru is ruled out, because of uncles. ‘Gandhi was always febharing Nehru,’ my uncles would say, ‘He was doing partiality.’ But even without the partiality, Nehru was no pushover. He was a patriot from an early age. He joined the Indian National Congress long before Gandhi. He was the son of Motilal Nehru, a respected leader. He was an excellent speaker. He would have been a player in the Congress, through the 20s and the 30s, and been pointed out as a leftie at tea parties.

Like Nehru, Subhash Bose turned nationalist early, punching out professors in college, and resigning from the Indian Civil Service, because he didn’t want to serve the British. He was a disciple of C.R. Das, who achieved the remarkable feat of uniting Bengali Muslims with Bengali Hindus. No one else has managed that before or since. Bose joined the Congress in 1921. He admired Gandhi as a great man, but his thinking was very different.

There might never have been a Sardar Patel, though. For the first 42 years of his life, Vallabhbhai Patel took no interest in politics. He was a good citizen and a good family man, practicing law and building his fortune. Of all our great men, he was the one who was inspired into action by Gandhi, suddenly, in his middle age. The attraction must have been strong. Without it, maybe he would have remained a respected member of the local community, known for his clear thinking, the right man to go to with any problem, never in his wildest dreams imagining that one day he would become a statue.

Which leaves a Congress with Nehru and Bose as key leaders, along with one Mr. Jinnah. A fine mind, but a cold fish. Both Nehru and Bose are impatient men. With them in charge, the Congress pushes for freedom sooner. With no Gandhi to hold them back, they are more militant. They avoid large-scale violence, but the British are getting nervous. Meanwhile, the Indian Army is getting restless. The British raise salaries, which they can ill afford to do.

In both 1938 and 1939, Bose becomes the President of the Congress. People notice that some of the Congress volunteers are wearing khaki, and marching. Jinnah and Azad are both part of the team, and no one has ever mentioned the word ‘partition’. Jinnah finds Bose’s costumes funny, but he can deal with him.

Nehru and Bose part company when World War 2 breaks out. Nehru’s heart is with Britain. He sees Hitler as evil. Bose sees him as opportunity. He has always been interested in the army. At this crucial moment, he is in India, surrounded by Indian soldiers. Many historians believe the Indian Naval Mutiny of 1946 was the final nail in the British coffin. In this scenario, with Bose to inspire them, things happen faster.

By 1942, the Indian Army is disintegrating, fatally weakening the British war effort. Some have broken away and formed units of the Indian National Army. Others stay true to their salt, but they will not fight. The Japanese win the Battle of Kohima, supported by overseas elements of the Indian National Army, whose ranks swell as they advance. They beat the British in a series of battles, till they break through to the plains of Bengal, where the Japanese are thrilled to find so much fish. Netaji gives the order to rise, and New Delhi falls in a military coup. Garrisons across Western and Southern India rally to his name. It’s worth remembering that in the Congress elections of 1938, every single Congress delegate from the South voted for him.

Netaji is declared Supreme Leader of India, with Nehru as his Foreign Minister. Nehru is not sure where this is going, but he is happy that the country is free. Netaji’s first priority is to launch elements of the Indian National Army into Hyderabad, which crumbles after some initial resistance. His troops march into several other princely states. He has to be quick. He wants to take them before the advancing Japanese. They are his allies, but he has trust issues. Then the Americans drop the bomb on Japan, and the war is over.

The Japanese surrender and give up their possessions. These include Burma, the whole of the North-East and Bengal Province. But who do they give it back to? To the British, or to Bose? The British are exhausted. The remnants of the British Army are itching to go back to England and kick Winston Churchill in the pants. They are happy to let go.

But Subhash Chandra Bose is a notorious leftie. The first thing he has done after becoming Supreme Commander is request Stalin for support. Stalin is busy taking over Europe. He is distracted, but sympathetic. Nehru flies down to Moscow, and their meeting is a great success. As usual, he floors all the women.

The Americans cannot allow this. They make the British take back the Japanese possessions. A much smaller British India is re-established, right next to the freshly independent Republic of India, where boots echo in the corridors, and Nehru and Jinnah are whispering to each other about forming a resistance movement.

An iron curtain falls over the subcontinent. Soon enough, a wall goes up, somewhere in the region of Patna.

Note: The above post edited to correct an error. The previous copy mentioned 1920 as the year in which Gandhi returned to India when it should have been 1915.