The Chandrasekhar Limit Applied to Populist Economics

The Indian-American astrophysicist Dr. S. Chandrasekhar first proposed what is now called the Chandrasekhar limit. It says that stars that are 1.4 times and more than the mass of the sun would end up as Black-holes because the increased gravitational pull at this point would force it to collapse into itself. Physics is an exact science, that’s why there is a precise value to the Chandrasekhar limit. On broadly similar lines, I propose a limit (open to some degree of approximation) applicable to economic policies identified with populism. This limit would mark the point at which it all begins to crumble.

Let me start off with a thought about what constitutes populism.

In simple terms, an economy is about people who work to produce goods and services and who get paid for their efforts in some proportion to the quality of the effort they have put in. It’s somewhat like a basket of apples from which you are allowed to take out broadly in line with what you have put in. For the purpose of this article, let’s call it the “real” economy because it is produces real goods and services which meet the demands of people and for which they willingly pay a price. At the same time, modern economies also have a significant “make believe” component where the rules about taking out only so much that you have put in don’t apply. The world of entitlements is part of this make-believe. Because the government has affixed a label on you— BPL, aged, unemployed, landless, vulnerable section etc.—you are allowed the right to take out from the basket even as you don’t put in anything, or put in a lot less.

Populism may now be defined as policies that have the deliberate effect of expanding the make believe economy with its core constituency of free riders. The objective is to give shape to a class of voters so beholden to you they keep on voting for you. In developing countries that also happen to be democracies, the poor have the numbers and the votes, and this is an easy way to get those votes. However, economics based on delusion always has a limited shelf life, and for all its compelling electoral logic, the expansion of the entitlement economy cannot go on forever. Sooner or later, something has to give way… after all, populism fools the electorate, but there’s no fooling the laws of economics. Where, then, lies the trigger? The answer is no surprise to us in India. It is inflation.

Expansion of the make-believe economy is about paying people even as they don’t put in anything into the basket. So long as the real economy is able to make up for these giveaways with increased output, there isn’t too much of a problem. Indeed, the modern welfare state with its social safety nets is actually about the productive economy sustaining a smaller, manageable component of make-believe welfare, admittedly for a larger cause.

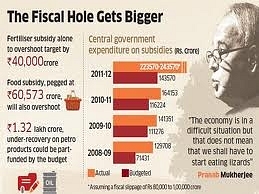

On the other hand, in poor countries, populism carries the seeds of its own destruction. Because it succeeds so well in pulling in the votes, to a self-serving politician untroubled by anything like a longer term vision, it seems a sure-fire method of winning elections. Spending on entitlements increases by leaps and bounds, drawing more people into this world of make-believe. Since money is not an issue—governments borrow and print money at will—there is a lot of it flooding into the economy. It gives rise to inflation. It becomes worse when the expansion of the make-believe economy begins to constrain the real economy’s ability to produce real goods and services, causing output to stagnate, and even shrink. At this point, inflation becomes toxic, serving as a natural brake on the unchecked expansion of entitlements and subsidies.

Here’s an interesting thought. Populism works much like alcohol. As the glasses are clinked and as the first few sips take hold, it spreads good cheer and a warm glow. A while later, more of the same follows, and folks become noisy and boisterous. Saner voices step in with calls for restraint but they aren’t heeded. The party becomes a riot and a lot of good people wake up the next day with an acute hangover. Because populism gets going by handing out money to a lot of people who have done nothing to earn it, the initial impact is to spread cheer all around, particularly when the money being passed around has been generated by liberal borrowings or by running the printing presses at full steam. A lot of “good” is being done without anyone paying for it. So it seems.

Soon, all the money that is printed and all the money that is borrowed and handed out for nothing, ends up in the market chasing a stagnant output of goods and services; the classic definition of inflation as “too much money chasing too few goods”. This is the point when the mood begins to sour and populism is up against its inherent limitations. High inflation is deeply unpopular with the masses and the government faces a run on its popularity. Even the poor who have benefited so far would desert its ranks because the money they get for free is increasingly worth less.

Getting back to Dr. Chandrasekhar, it should now be possible to define an “inflation limit” at which populism loses its plot, and is forced to give way to hard-nosed fiscal prudence. But, instead of one inflexibly defined limit applicable for all, it perhaps makes sense to look at each country separately, with due consideration for its trends and tolerances. For example, in Venezuela, where Hugo Chavez’s economic policies define the word populism in all its short-sightedness, inflation has ruled in the 20 to 30 percent band for many years now and yet he retains a firm grip on power. It is of course a big help that Venezuela earns substantially from oil exports which gives Chavez the luxury of free money to throw around.

In India, on the other hand, in the six years up to 2006, headline inflation hovered around the five percent mark, within the accepted comfort level. The subsequent increase to near double digits has darkened the mood and dented the economy. Recall that it all began with a spectacular (and continuing) rise in food prices, particularly the more expensive protein-rich items. This was initially interpreted as a welcome sign of increasing income levels in the rural economy thanks to the UPA government’s inclusion agenda. It fuelled loose talk in the media about food inflation caused by “rising prosperity levels”, linked directly to the NREGA.

As is increasingly clear now, this was always a fallacy. Entitlements that hand out money to the poor with little visible output in return are effectively a subtle transfer of wealth out of the hands of the savers, into the hands of the recipients. It is not prosperity but the illusion of prosperity. It is like the cheer that spreads when the first few sips of alcohol take hold. That illusion is now beginning to get punctured with rampant inflation and India’s vaunted growth story on the verge of tipping over. The party is out of hand.

What then is the “inflation limit” to populism in the Indian context? I would argue that our current inflation rates —food prices out of control and economy-wide inflation in double digits, all stubbornly holding out for extended periods of two, three or more years—is a classic example of the breach of the inflation limit to populism. After all, economists, the financial markets, Indian and foreign investors, even the UPA government that’s held power for eight years with entitlements as the cornerstone of its economic agenda, recognize that at these levels India’s wider economic prospects are under grave threat. More to the point, the Congress party has understood the hard way that high prices for essential commodities spell trouble at the polls. Aah… if only the genie could be pushed back into the bottle!

As for a more precisely calibrated inflation limit to populism, I invite the professional economists to weigh in with ideas and analyses. And whoever can convincingly arrive at one may then consider giving her name to it.