The Politically Correct "Realism" of Haider

Vishal Bhardwaj’s superficial and clichéd film Haider tries to draw tacit (and erroneous) parallels between Gaza and Kashmir through his Chomsky-esque reference to Kashmir as a prison

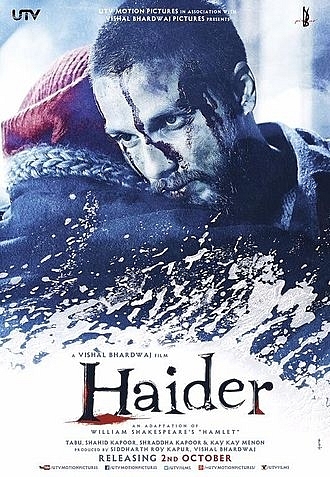

Since its release on October 2, hardcore movie buffs in India couldn’t have ignored the encomiums that have been heaped on Vishal Bhardwaj’s adaptation of ‘Hamlet’, Haider, for its “realism” (read anti-Indian State “ism”). I, for one, have loved Bhardwaj’s past adaptations of the Bard’s work such as Maqbool (‘Macbeth’) and Omkara (‘Othello’), particularly for his mastery of sound and the earthy witty dialogues which bear his personal signature. Naturally, I couldn’t stay away from Haider despite its discernible “realist” tone from the trailers. I am not a professional film critic for I have no knowledge of the technical nuances of film-making. I am just another lover of cinema with my share of political predilections. Therefore, this is not a review of the film, but my reaction to it.

As far as the basic plot goes, the film is an adaptation of Shakespeare’s ‘Hamlet’ set in terror-torn Kashmir of the early 90s with the “disappearance” of Kashmiri civilians forming the crucible for the lead character Haider’s Hamletian inner turmoil. ‘Hamlet’ merely provides a rudimentary template for the movie, with highlights from the play serving to remind the viewer of the movie’s ostensible claim of being an adaptation of it.

The actual focus of the movie and the intent of the filmmaker, however, seem steeped in politics and ideology. Simply put, the alibi that the movie is just an innocent silver screen adaptation of a celebrated play, devoid of any political message or proclivity, may not cut much ice given the treatment of the script, coupled with the fact that Basharat Peer has co-written the movie.

One cannot and doesn’t hold it against the makers of the movie for using the play as a conduit to convey their views on a contemporary issue. But having done so, it is expected of them to stand by the decision and own up to it instead of evading scrutiny of their views and alleged factual premises.

In other words, the filmmakers do not have the option of cherry picking facts and historical events under the guise of cinematic or artistic liberty when dealing with a subject as sensitive and emotive as Kashmir, since selective representation leads to the presumption that a certain agenda is being advanced through the movie at the expense of the whole truth.

Personally, I am of the opinion that the movie isn’t balanced or honest in its portrayal of the origins of the dispute, or the situation in Kashmir and its consequences for all communities to whom Kashmir belongs. In fact, Bhardwaj’s attempts at lending balance to his views come across as half-hearted. Although he appears to condemn the path of violence opted by the separatists in Kashmir, he also tacitly justifies it (through the character arc of Haider) as a natural reaction to the Indian Army’s alleged excesses in the Valley under the Armed Forces Special Powers Act (AFSPA).

Despite the charitable references to the Army’s yeoman work during the recent floods at the fag end of the film (by which time the damage is already done), Haider has the cumulative effect of painting the Army and the Indian State with a manipulative and diabolical brush.

Curiously, characters playing the roles of the officers of the Indian Army have been given South Indian names like ‘T S Murthy’and ‘Nagarajan’, who are pejoratively and tastelessly referred to as “Masala Dosa” by Shraddha Kapoor’s character. Probably, it was the director’s intent to give the impression that Indians from the South, who, according to him, do not understand the politics and sensibilities of Kashmir, are typically posted in Kashmir by the Army to handle the situation more “objectively” (read ruthlessly). Whatever the intent, the end result is condescending to say the least. It is indeed surprising that to endear himself to the Kashmiri Muslims and to pander to the anti-India gallery, Bhardwaj has no qualms portraying other Indians in poor light. Barring Kulbhushan Kharbanda’s character, every other character who works with the Indian State to quell terrorism is portrayed as an opportunist and a betrayer of the “Kashmiri cause”.

Not to question the director’s freedom and prerogative, but if “realism” is truly Bhardwaj’s obsession, surely the natural and human reaction of an Indian soldier who finds himself in an extremely hostile and treacherous environment is worth alluding to, in howsoever fleeting a manner.

But then that wouldn’t have won Bhardwaj the raving approval and endorsement of the left-liberal cabal in and outside Bollywood, nor would addressing the elephant in the room–the role of radical Islamists in Kashmir’s politics and its consequences for non-Muslims in Kashmir. That Bhardwaj’s take on Kashmir is superficial, clichéd and populist is borne from his effort to draw tacit parallels between Gaza and Kashmir through his Chomsky-esque reference to Kashmir as a prison. This must have really warmed the cockles of Kashmiri separatists who have left no stone unturned in internationalizing the dispute with the able support of the left and in drawing contrived symmetries between the Palestinians and Kashmiris.

Contrived, because the inconvenient truth of the ethnic cleansing and forced exodus of half a million Kashmiri Hindus exposes the religious bigotry of the so-called struggle for self-determination and the incredulous claim that the dispute is purely political.

If the dispute is truly political without a religious dimension to it, how does Bhardwaj justify the rape, genocide and expulsion of Kashmiri Hindus? Ah that’s simple. Bhardwaj explains this away by making the Indian Army the spokesperson of the plight of Kashmiri Hindus, in effect reinforcing the image of the latter as “informers/mukhbirs” of the Indian State and the Army. Therefore, the “natural reaction” of Kashmiris towards the Army, according to Bhardwaj, can legitimately extend to wiping out an entire community and culture for being loyal to the Indian Union.

You see, every community, except the Hindus, is entitled to “react naturally” to alleged excesses and perceived victimization. “Natural reaction” is only human and never communal when it comes from non-Hindus, more so when it is directed at Hindus.

Also, as required by the only acceptable definition of “secularism” and “syncretic tradition” in this great land of ours, every movie on Kashmir must necessarily accept and perpetuate the myth that Kashmir has always been a Muslim majority region, and its Hindu roots and remnants (if any) are but a vestige of the past best forgotten and stamped out to give way to a more “secular” present.

For instance, in the movie, when an Army officer asks the character Haider his native place, Shahid Kapoor’s Haider answers “Islamabad” with righteous defiance just to irk the officer. We are then told that Anantnag (where Basharat Peer hails from) is locally referred to as “Islamabad”, bringing to memory the recent controversy surrounding the re-naming of the Shankaracharya Temple in Srinagar to Takht-e-Sulaiman. Conveniently again, Bhardwaj does not dwell on the issue further because we wouldn’t want to hurt “secular” sentiments, would we?

In the interest of preserving secular clichés and harmony, we must let remnants of Hindu culture such as temples serve as props for a shoot, or more frequently as natural targets of natural reactions from the victimized denizens of the Valley.

Clearly, Bhardwaj’s realism is a politically correct one which treads the safe oft-beaten path of lambasting the Indian State and holding its Army solely responsible for the radicalization of Kashmiri youth, comfortably ignoring the pivotal role of Islamist supremacists.

The politically incorrect version would be one where the absence of an armed struggle by Kashmiri Hindus in response to the savagery meted out to them and their culture is highlighted to drive home the message of peace and the futility of vengeance. But then, that version would have been received with stone-pelting (with ample encouragement from “brothers” across the border), a not-so-non-violent demand for a ban on the movie, fatwas calling for the heads of the entire crew of the film, threats from the underworld, and the “communal” tag from “intellectuals” in Bollywood.

Now which street smart director from Bollywood would want that kind of trouble on his hands? Isn’t it easier to simply play the righteous rebel by targeting the soft Indian State? Smart move Vishal!

Speaking of stone-pelting and assorted expressions of outrage, how come the Valley has not “reacted naturally” to the portrayal of a Kashmiri Muslim woman as an adulteress with not-so-filial love for her son? Or did the anti-India bile in the movie more than compensate for this unpardonable sin?