When Rahul spoke..

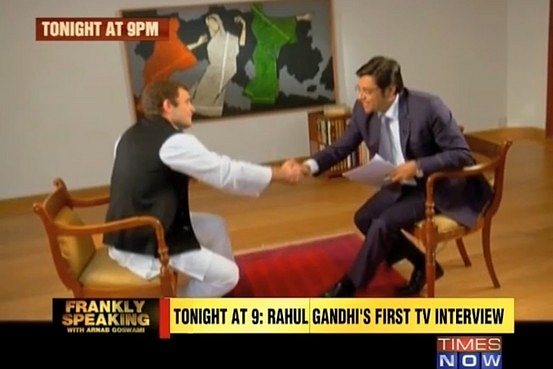

By the end of Rahul Gandhi’s interview with Arnab Goswami, it was hard not to feel sympathy for the man. It was the look of somebody who had always stared into a mirror and found his own beauty described to him. Only this time, under the glare of a camera and a country that his Party seeks to rule, there was no chorus to describe him. What the disappearance of such props do is hard to imagine. For most us have no such luxury. What we did see today, was Mr. Gandhi’s mind struggling to find its coordinates. It scrambled, it meandered. It lacked the discipline to persevere through an argument. The third-person intuition, that all great politicians develop, to recognize how one appears the minds of others, failed Mr. Gandhi. Words arrived first, ideas followed later.

At some point he ended up in that half-house between an indignation of having to put up with Mr. Goswami’s efforts to ground the answers in the here-and-now and the need of the hour to appear accountable, reasonable and, perhaps, even Prime Ministerial. To Mr. Gandhi’s handlers, it must have been a terrifying experience. To be unprepared is one thing, to have one’s desperate fumbling telecast to millions is another. The feeling of sympathy that emerges is not solely because he had a less-than-stellar showing; but because what we had suspected, which is that Prince had no Clothes, was not only true but that we have come face to face with a man who is, well, simply banal.

Mr. Gandhi’s answers to most questions were the unthinking bureaucratese that transnational consultants and image experts peddle. Words – empowerment, women’s participation, devolution of power, transparency – that when inserted into conversations are presumed to grant moral superiority to the speaker and a deeper insight into the conditions of all that ails man. In our political system, which has little use for highmindedness except as theatrical devices and an aesthetic disgust for the other side – such words presumably provide a talismanic power to the speaker. He appears above the fray. When Binayak Sen talks of devolution of power or Aruna Roy talks of transparency, there is a life time of commitment, struggle and sacrifice that inform those words. Mr. Gandhi – like the English speaking, upwardly mobile, double-tongued Indian middle class – uses these words in ways to merely buy himself credibility after presiding over a government that is knee deep in opaqueness, corruption and arbitrariness of power. That the very same politicians now mouth these words – words, with long and complicated histories – as mere pieties, reveals how they operate in day to day life. Mr. Gandhi spoke words that has allowed him to unthinkingly convince himself that he is fighting a good fight.

But what they reveal are the sad fact of a man at the precipice of his middle age who has become enamored of his moral certainties and, in absence of critical reflection, fallen in love with his world view. Ironically, that he had to repeatedly assert he was a “serious politician”, that he was all about “deep thinking”, that he played for the “long term” – reveals somebody who himself suspects that these words ring hollow. Perhaps, I am being harsh, but we have little to go by despite a decade or more of public life. He has neither held executive office despite his own government running the country nor has he demonstrated the desire to radically reinvent his own party, in the way AAP has gone about it. The reality is that he accrues all the benefits of being at the top of a large, imperial party organization; but his vanity conceives of himself as a radical who shall fight it out. He tells himself repeatedly in the interview that “I am a deep thinker”; a tactic that is no different than boxers who tell themselves of their own invincibility before a match.

Yet, given his schizoid realities, the viewer must face up to the fact that either Mr. Gandhi doesn’t have the courage to break past the faux world he has been living within; or worse, that so comfortable is he in this insider-outsider role that he has cynically (or foolishly) reconciled to a kind of double life. One marked by well-meaning angst on one end and expedient condoning of malfeasance on the other. In this, certainly, Mr. Gandhi is not alone in our political system. But, he certainly is the more prominent of such cases of self-validation and self-deception.

Since the 4-0 electoral disaster in late 2013, defeat, like a ghoul that has made itself comfortable atop Mr. Gandhi’s weary shoulders, stares on into his future. The Modi juggernaut meanwhile continues, threatening poll data collectors with off-the-chart readings. In an internal poll data of the Congress leaked to the AP, estimates range from 75-80 seats in the coming elections (out of the total 542). In 30 years since 1984, when the Congress won 409 seats – the decline, like Mr. Gandhi’s confidence during today’s interview, has been steady and, well, secular. The reasons are many and depends on whom you ask. But if Mr. Gandhi in his present avatar was meant to be the one who revives the Congress Party from the soporific and corrupt UPA-2 government, today’s interview puts a sword to that idea.

At the heart of the matter is the question of how he sees the world. His responses revealed a man, about whom apriori not much is ‘really’ known. And that which is, is carefully stage-managed. Despite this shroud of calibrated exposure, like other children of prominent families elsewhere, he has successfully failed upwards in his life. When presented by Mr. Goswami with Subramaniam Swamy’s doubts about Mr. Gandhi’s academic credentials, his response was telling. Over and beyond the rightfully expressed sense of frustration, he did what comes naturally to him. He cloaked himself in a sanctimonious self-defense that Mr. Swamy, no wall-flower himself, had been after his family “for 40 years”. And being attacked was, well, just part of the great set of responsibilities he shouldered as young scion of a father-less family. No doubt his family – presumably, his sister and mother; and may be even his controversial brother-in-law – are not just his source of refuge from the world, but also from whom he derives his self-lacerating notions of sacrifice and responsibilities.

This world view of we-against-the-world is a product of years of conditioning and narratives told to him by well wishers, sycophants and even enemies of the Gandhi family. The perils are obvious: a narcissistic faith in his Family as the beachhead that stands between the bearded ‘bhagwa’ (saffron) barbarians at the gates and Civilization on the other, defended and paid for by the blood of his grandmother and father. It is instructive that in an entire hour long interview, there were two names that never came up, at least in any active sense. Mahatma Gandhi, and more tellingly, Jawaharlal Nehru. No doubt, they belong to a past that young Mr. Gandhi genuflects to, but in of itself neither of them matter to his sense of being, his ideas of himself. In a way, he merely channels what his mother has consistently told all who care to listen: the domineering influence of Indira Gandhi on her formative days in India and the loving presence of Rajiv Gandhi as her doting companion.

Alas, for the country however, neither of the two deceased Gandhis are beacons who shed light on critical matters of the hour: how to rebuild institutions, how to excise the tumors of corruption, how to combat identity politics.

To all these problems, what the young Mr. Gandhi’s answers reveal is how atrophied his intellectual growth has been, while still that he has managed to internalize mantras that give him a veneer of sophistication. Perhaps, amidst his well-wishers in the Congress that is enough. In an effort to pull rank over Mr. Goswami their conversation turned to that final institutional arbiter of Indian elites – their experiences at Oxford and Cambridge. But unlike in the days of Motilal Nehru, such institutions aren’t merely privy to blue blooded India. Talent, hard work, chutzpah and faith in oneself can open many doors. Mr. Goswami embodies that in more ways than one.

In fact in Mr. Gandhi’s own government, there are ministers who come from humble backgrounds, who have gone onto do Masters at IIT, PhDs in prestigious American and English Universities, some attained their PhD at as young an age as 23. Having failed to assert his own superiority on grounds of education, Mr. Gandhi decided to expand on his views on ‘the system’.

He insisted, the problem of India is the “system” that is in place. The perils of getting vocabulary right when assessing problems have rarely been as visible. One who sees in India a ‘system’ believes that it can be fixed by measures that are manageable, manipulable. It is a world view that has faith in a mechanistic cause-and-effect relationship. Yet, the reality of Indian public life is that what we have is not a ‘system’ but nebulous array of self-interests that, like algae atop the many rivers of Indic lives, is afloat. It survives, it sometimes shrinks and it sometime engorges itself on nutrients from the public commons.

The Indian system is a living, throbbing, self-arranging phenomena that has only one dharma: survival. To tackle such an epiphenomena, one needs to radically excise its controls over common lives. It means to reduce our faith in the State as the arbiter of wisdom. It means to recognize that the hubris of ‘system’ builders is more dangerous and corrosive than what it seeks to cure.

Mr. Gandhi, it is evident, has been spoon fed on a steady diet of standard Left-fare that draws its philosophic roots from world-systems of Hegel, Marx and Walrasian neo-classical economics. It is a view that has at its root, articles of faith that things can be ‘right’, if only x happened or if process y fell in place. It is a world view of MBAs, of technocrats who view the world as a problem to be solved. In here is revealed Mr. Gandhi’s belief that he can ‘know’ the actual relationship between cause and effect. It is a view that doesn’t have contingency of knowledge, that doesn’t have humility at its core, that has no philosophic outlook as far as knowledge or knowability is concerned. It is a view that believes it has the means to aggregate, analyze and ascertain facts from the fantastical looms that the Indian bureaucracy can spin around him. His faith to correct the deep problems of the ‘system’ leads him to repeatedly conclude that the Indian system is fundamentally opaque, and his efforts to instill ‘openness’ is the cure to all. To this end, he repeats his faith in the RTI (Right to Information Act) as the panacea for ills.

Openness, like many of the words he used with near religious fervor, means many things to many people; but nothing refutes his claims of ‘openness’ when his party’s upper echelons are stuffed with those who began life with an advantage. As Mr. Goswami bravely pointed out, the party’s upper rafters are filled with children of the late Mr. Pilot and Mr. Scindia, Mr. Sangma, Mr. Deora and the late Rajiv Gandhi himself. To counter this, Mr. Gandhi could have pointed at the life story of Meenakshi Natarajan as an example of what changes he intends. But, either he didn’t have his wits together or so overwhelmed was he by the evidence that he thought it best not to counter it.

To a less than sympathetic observer, all this merely shows is that his strategy of inculcating ‘openness’ within the Congress Party is more of a tactical effort to fill the stalls with his loyalists and slowly phase out the old guard; but in of itself, the only tradeable currency will be loyalty to the Family. The powers vested in the representatives will be measured by the degrees of separation from Mr. Gandhi, and in due course perhaps, even Priyanka Gandhi’s children.

It is at such conversational cul de sac-s that Mr. Gandhi sought to differentiate his Party from the other. Over and beyond the curved condescension of his lips when talking about the Aam Aadmi Party, or the categorical insistence, that unlike the BJP, the Congress was inclusive and more importantly reluctant to concentrate power. Yet, if one is sees the ease with which Jayanthi Natarajan was fired, or in a complete mockery of, what Mr. Gandhi holds as sacrosanct, the ‘process’, the ease with which 9 cylinders of LPG were increased to 12 at his mere public exhortation at Talkatora Stadium, tells that Mr. Gandhi is no longer an ingenue politician. Those who suspect he is weak are mistaken. It is just that he is wrong, which makes his claims of strength all the more wrongheaded. He has clearly the ability to pick and choose evidence and has cultivated a healthy lack of self-awareness – both key talents for all successful politicians. None of this, of course, is new in politicians, but so little is really known about Mr. Gandhi’s real thinking that the banality of his fervor catches one by surprise. I suppose, somewhere deep within, one imagines that the Gods perhaps don’t have clay feet.

Alas, today we realized, not only is that Mr. Gandhi neither is a messiah nor a political God who offers a communal ecstasy but, alas, he is not even a leader who can lead this Party, far less this difficult and challenging country. He is perhaps the perfect representation of our facile, media soaked culture. A carefully stage-managed creation of his mother and party apparatchiks who have poured their own inchoate and incomplete aspirations into this like-able young man, who grew up to believe them and now finds himself inadequately prepared for the task. It is useful to note that a wise and senior reporter like Chitra Subramaniam said in no uncertain terms: shame on those who set him up.

This view, in a way, of course, absolves Mr. Gandhi of all personal responsibility, makes him into a ‘passive’ recipient of machinations and Fate – which naturally only casts him in an even poorer light. What is clear is that Mr. Gandhi’s back-room advisors have done him little favor. They sought to adopt an Obama-style model of messaging and communication. Much as ‘hope‘ became Mr. Obama’s cri de coeur, it is evident that Mr. Gandhi wanted ‘empowerment‘ to be his calling card. It is an unpardonable conceptual fumble in an election year. It is a meaningless term when Indians still derive their identities from families, castes and communities. To empower Indians, presumes Mr. Gandhi knows of ways to help individuals circumvent the consequent social pressures and will help them find their own footing.

It is a manifestly conceited idea – which yet again reflects the hubris of a Left-leaning perspective that presumes that the vanguard can shower in enlightenment and if not, to wit, throw in a subsidy program at the tax payers expense. The mood of the hour is different. Indians want governments to step out of their daily routines, to make it easier to conduct their lives, to grant freedoms to make choices that are in proportion and contingent with the world-views they emerge out of. Our process, systems and linkages between institutions have weakened due to abuse and neglect, and what Indians aspire for is a government that hopefully helps them to make do with less ‘jugaad’ in their lives.

This is not to discount the importance of social programs but instead to ask whether such ‘empowerment’ formulae have consequences that go well beyond economic promise. Do they vitiate other macro-phenomena? Does it upset the larger stability of the “system”? When Mr. Goswami mentioned the exorbitant rise of consumer prices, Mr. Gandhi had little of use to say except that he is “working with the government”. Such a glib, unthinking response belies the complexity of the phenomena at hand. Mr. Obama – with whom many in Congress Party try to forcefully compare Mr. Gandhi – in contrast, takes upon himself to educate his listeners about the complex interlinkages and feed back loops in play. He calls such opportunities to communicate about complex issues a ‘teachable moment’. To do so diligently, conscientiously not only reveals a respect for the intelligence of one’s audience but also tells us that he has thought through the problems at hand.

One may disagree and quibble about the solutions, but that is a debate which elevates any politician in the eyes of an informed citizenry. When Mr. Vajpayee insisted on keeping on the walls of the External Affairs Ministry photos of Mr. Nehru, as the historian Ramachandra Guha writes, what it reveals is the respect that Mr. Nehru evoked in his ideological bete-noire. Mr. Gandhi had the opportunity to tell us, to teach us what he has learned up close from the seats of power about what ails India, how does information move along the chain of command, what are the bottlenecks. He failed. So, the next time, when Subramaniam Swamy calls him, with barely disguised contempt, ‘buddhu‘ – there isn’t much that those who seek to defend Mr. Gandhi can point out at.

Yet these are matters of intellectual heft and cleverness – neither of which are, in the final calculus, most important in the life of a politician. But what is relevant and remembered is the courage shown to face up to mistakes of the past. And it is in this line of questioning that Mr. Gandhi failed most unconscionably. Seeking to make equivocations and indulging in an algebra of equivalences between the 1984 and 2002 riots, Mr. Gandhi reveled a mind that was fundamentally timid. One that when cornered doesn’t have the courage to push back as Mr. Modi does, or the clarity of morals to see what is being asked of him at the hour as Mahatma Gandhi, Jawaharlal Nehru and Sardar Patel had done. It doesn’t take much to see that the Sikhs (in case it matters, it is ‘Sikh’ not ‘Seekh’) have given up on the possibility of justice. It is a wound that they have reconciled to living with. It will remain open and festering till that generation of Sikhs pass away. Active condoning by the Congress party led to the killings. What the Sikhs want now, clearly, is a respect for the memory of their loved ones. At the least, Mr. Gandhi ought to have come prepared.

Perhaps, given interminable number of yojanas called Indira this and Rajiv that, perhaps he could have offered to build a monument for those who died in that planned and organized butchery. Many of whose names, we will never know. Mr. Gandhi spent many a sentence extolling the death and sacrifices of his grandmother, but barely a sentence to express contrition or emotion for those men pulled out of buses, their hair forcibly shorn and stabbed, for those women who were raped, for those children who were hacked away in the bazaars, for those old who were burnt in public as came out of the gurudwaras. To equivocate is unacceptable. And to suggest that the government of the day made efforts to prevent the murders reveals how masterfully Mr. Gandhi has learned the art of dissembling in face of uncomfortable facts.

The only moment of emotion that Mr. Gandhi revealed was when matters turned to how he takes defeat and the support from his steady-as-a-rock sister. By then, even Mr. Goswami – like a fast bowler who toys with a tail-ender – had begun to sound a note of reconciliation or two. And precisely then, Mr. Gandhi tried to go on an offensive and accuse the media of not taking up issues of interest to him. How to grow India, how the industrial corridors purportedly is where India’s manufacturing future lies, how RTI (oh, the RTI) is the weapon against corruption – and so on. Predictably, not a mention of Mr. Khemka, Mr. Vadra and other unmentionables made to the fore. This evident frustration suggests that Mr. Gandhi was led into an ambush. He had come prepared to pontificate on ‘big‘ ideas, but somehow the upper echelons of the Times of India group decided to give him an ‘Arnab’-treatment. They decided to defeat him with a thousand cuts.

The consequence is that in a keenly contested election year, when a note of stridency would have not been out of place, so worn was Mr. Gandhi by the end, that he was reluctant to name Mr. Modi in person, far less lash out. And it at this moment, one is astounded Mr. Gandhi’s relative lack of political ruthlessness. In a conversation about Gujarat riots, to not mention by name Maya Kodnani, who served in Mr. Modi’s administration and now serves a jail sentence, or Babu Bajrangi, or the accusations of the police commission R. B. Sreekumar against Mr. Modi, or the direct testimony of Harsh Mandher or the findings of Siddharth Varadarajan et al or the political scores against Cedric Prakash, Mallika Sarabhai and others – reveals that Mr. Gandhi neither knows the details of the Gujarat riots, except in terms of parlor room generalities, or that he has satisfied himself by the supposed culpability of Mr. Modi, which of course is self-evident to him, his coterie and thus presumably to the rest of us. He presumes that India would just fall in line and see Mr. Modi’s complicity in the riots.

Either Mr. Gandhi is extraordinarily polite or he just has never gotten into a school yard fight – where unless you punch yourself somebody in public, you get no respect. If there is anybody who deserves a rhetorical punch or two from Mr. Gandhi, it is Mr. Modi who has been crass, personal and insulting. It is in this context when Mr. Gandhi says he has “no fire in his belly for power”, we can only but believe him. Power, and all its accoutrement, have come all too easily to him. And he is content with a calorie-controlled diet of power, where no body can publicly accuse him of being gluttonous, or as selfish. It may come as news to him that there is nothing more disingenuous, and if true even more dispiriting, than a politician who says he has no interest in grabbing power. In a way, his statement reminded me of what Sylvester Stallone said: “I could play Hamlet if I wanted to. I just don’t want to.”

In the end, well, it was all too tame and pitiable. It is an uneven match. Mr. Modi, who has come up the hard way in life, reveals himself as a strapping, brutish, effective satrap who has consolidated power, cultivated loyalties, threatened opponents and now seeks to become the ruler of India. He wants power, he wants to effect change. His contempts and passions come from a deep and maybe dark place within, which after years in the wilderness as a second rung party functionary, who had neither the base nor family connections, the cauldron of complexes define him. Resentment is a terrific spur. In Hamish MacDonald’s “The Polyester Prince”, there is a wonderful story of how, when Dhirubhai Ambani was disallowed from entering into drinking clubs officiated by the patrician Nusli Wadia, Mr. Ambani vowed to destroy Bombay Dyeing. And so, he did. Mr. Gandhi comes across as Paris to Mr. Modi’s Agamemnon.

The reason Mr. Modi connects with the young, not withstanding the riots of Gujarat and the accompanying bigotry, is that he represents the primeval struggles that many a young Indian goes through today. In Goa when he challenged the audience and asked aloud if they want to suffer as their parents did, there is an authenticity in that interrogative question which is hard to shake away. A messianic conviction in his own world view. One can never see Mr. Gandhi speak to the people from that inner core, which as we discovered today is neither too deep nor too dark. It is shallow and bland. Mr. Gandhi did himself no favor by being ill prepared. We learnt that behind the cotton-white Congress kurta is a young man who has erected psychological defenses and justifications that guard mythic memories of his father and grandmother, dutifully and lovingly tended to by his mother and sister. His is a victim’s mindset. It is how he sees India. It is why he finds the idea of empowering Indians so attractive.

Alas, the country is young and with little memory for the sacrifices of his family. Today’s India is a scrappy, aggressive and an impudent nation. It may need empowerment – education, health, manufacturing, gender equality – but it cannot be brought by the vocabularies of noblesse oblige that Mr. Gandhi and many in the Congress speak today. That was a language that the more genteel generation of my own parents had reconciled with. They took inequity, insults and insecurities in their stride and tried to make a good life for their children. Today’s India, however, speaks the language of naked ambition, of angered frustration and thick-lipped carnality. It sees those who have social infrastructure build on it, while those who don’t languish in the purgatories of Indian social life. If Mr. Modi increasingly seems to be able to cut across caste barrier and consolidate in places like Western UP, it is because he has the first mover advantage in tapping the well-spring of resentment.

With an increasingly loyal base, he has begun to pivot and march to the center, admittedly a Hindu center, or rather a non-Islamic center of India. From this new vantage point, he speaks of growth, of transparency, of equality – the same words and ideas that Mr. Gandhi tries to articulate. In all of this, Mr. Modi reveals himself to be a master of political maneuvering, a great student of mass communication and most importantly, one who has an identifiable core – even if one may disagree with it. But, alas, if opinion polls are to be trusted, Mr. Gandhi is seen as an anodyne pretender. When he speaks, he is mocked out of pity. When Mr. Modi speaks, he is mocked for they fear he may do what he says. The media may call Rahul Gandhi, the prince. But by Machiavellian standards, it is Mr. Modi who is The Prince. When the young of India ask themselves, can I make something of myself despite lacking family connections, wealth and opportunities. They look around and ask – who has done that before me?

Not too surprisingly, as of now, Mr. Gandhi’s name never comes to mind.

(This piece was originally published at khasak)