A Brief History Of How Humans Slept From 8,000 BCE To Today

Evidence from history seems to suggest that the eight-hour sleep is a very recent phenomenon amongst humans

The past was no place for sleep.

You may think that the absence of traffic, and other machine-borne noises would make for restful nights. Or that a lower amount of people (the world’s population was less than a billion until the 1800s—it’s about seven times that now) would translate to less noise and therefore more peaceful sack time. But, apologies to prospective time travelers looking for some R&R: pre-industrial people rarely slept for eight hours in a row. In fact, judging from what we know of the past, it looks like we’re currently living in the golden age of rest.

Until the Neolithic era, humans lived in nomadic hunter-gatherer tribes, traveling in search of food and sleeping wherever predators weren’t. People didn’t have a reason to stay in a particular place before they knew how to grow crops and domesticate animals. It was probably only then that they gave a thought to having a semi-permanent place to sleep.

Remains of living spaces from the 8,000 BCE unearthed by archeologists in Southwestern Texas indicate the earliest draft beds made by humans were ground-based nests. Early man stuffed grass and other soft materials into shallow pits near the walls of caves. Judging from their small size and round shape, the cave dwellers, likely huddled in fetal positions until they’d mosey on over to rudimentary latrines at the back of the cave and relieve themselves.

Nights didn’t get much cozier as civilization advanced. For example, the Romans hated sleep. Sleep stood in the way of laying down roads, building aqueducts and conquering the world. As the popular Roman sayingCarpe Diem, or “seize the day” implies, Romans viewed daytimes as something in need of attack and the majority rose before dawn.

Nights and sleep, meanwhile, were just endured. Romans devoted little space for rest. One might think that those who created the Coliseum, Pantheon and other such lasting architectural works would have some beautiful boudoirs. But Roman bedrooms, called cubiculum, were small rooms with low ceilings and little decoration aside from darkness facilitating thick shutters. The occupant’s small wooden or metal bedframes would look like a sofa to modern observers. Wealthy Romans stuffed mattresses with feathers and the poor used hay.

Not all early civilizations treated rest with such little ceremony. The ancient Egyptians respected and feared sleep, believing it was a state close to death. They analyzed dreams for symbols and deeper meanings and believed dreams contained messages from gods. Beds and headrests were adorned with images of protector gods like Bes, a fierce fighter of demons. Wealthy Egyptians slept in bedframes that were low in the middle and rose up by the feet. Still, sleep was short and days were long.

In Monty Python’s immortal comedy “Monty Python and the Holy Grail”, every surface, object and person looks damp, smoked out and filthy. As it turns out, the comedy troupe was only barely exaggerating the disgusting circumstances of the Middle Ages. Everyone, rich and poor alike, smelled bad. Poop and smoke was everywhere, and diseases ran rampant due to lack of plumbing and the generally unsanitary conditions.

Days must have been unendurable, but it was worse at night: people huddled together in their collective filth to keep warm. Entire families slept as one in big, heat conserving beds. Privacy didn’t exist, even for rich people, whose servants often slept on straw mats within feet of their beds.

Filthy bodies weren’t the only things causing overnight smells. Until the 19th century proliferation of indoor toilets, people waking in the middle of the night with a full bladder or colon relieved themselves with chamber pots. For convenience, the excretion collectors were often kept as near to beds as possible, including beneath the frame. But people might have been distracted by the smells wafting from their chamber pots by the constant smell of smoke. People slept by fires and would sometimes place coals and embers from the fire under beds for added warmth.

The Renaissance represented a great awakening for Europe. But it was also a historic moment for sleep. People were innovating their approach to nighttime comfort. Ropes were stretched across bedframes to support mattresses and needed to be tightened nightly — some historians believe the phrase “sleep tight” is derived from the rigging-like bed support.

Around the same time in China, beds were becoming increasingly ornate. Like other furniture created during the Ming dynasty, which lasted from the 1300s to the 1600s, wooden bedframes were built big, with multiple intricately detailed bedposts. Too pretty to be reserved just for sleeping, beds were used during daytime to receive guests.

The industrial revolution changed everything about sleep. With the proliferation of artificial light, people stopped going to sleep shortly after sunset. Days got longer and, according to one historian, so did our periods of rest.

In his 2005 book “At Day’s Close: Night in Times Past”, Virginia Tech history professor A. Roger Ekirchcontends that eight hours of uninterrupted sleep is a recent social convention. Ekirch says that before the industrial revolution, people were bi-phasic, sleeping in two four-hour segments, with a period of late-night wakefulness in between. Ekirch, who identified references to this bifurcated bedtime in literature ranging from Homer’s “Iliad” to Chaucer’s “Canterbury Tales," said the wakeful period between sleep was a busy time.

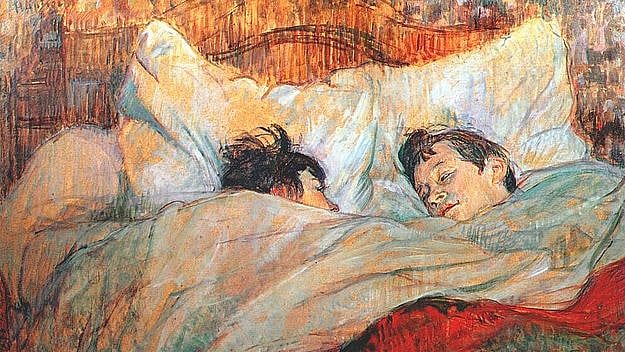

“Households when they awakened at night did a number of mundane chores that required little illumination or skill: They prayed, they meditated, they made love,” Ekirch said in an online interview. “A sixteenth century French physician was of the opinion that couples, after their first sleep, engage in connubial bliss when, as he put it, were better at it and enjoyed it more.”

Better technology and stricter work schedules forced many to forgo to the dark. In the years since, we’ve mostly adjusted to a monophasic schedule. That, for the most part, is a natural evolutionary process, one that suits us just fine. While the threat of blue light, bad diets and other such factors are threatening our sleep, at least we don’t have to deal with stiff bedframes, flaming piles of dookie and constant disease. Sanitation — and comfortable bedding — is a savior.

This piece was originally published on Van Winkle’s and has been republished here with permission. You can find the original piece here.