A Page Back In Time

Robert Jungk’s Brighter Than A Thousand Suns is no longer the definitive account of the making of the atom bomb. But for an insight into the early days of nuclear physics, it is still worth a read

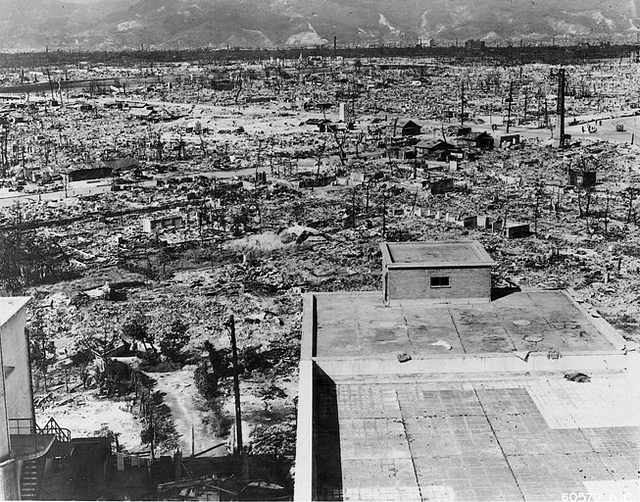

One of the lasting effects of the devastation wrought upon Hiroshima – 70 years ago – was how it changed the discourse regarding the survival and future of the human race. You did not have to wait for horned aliens or a particularly devious comet bolting towards your home planet to fear mass extinction. Human beings were capable of devising their own complete destruction, and the fate of Hiroshima and Nagasaki bore testimony to that.

It did not stop other nations from developing or acquiring their own nuclear weapon stockpile. Deterrence became the keyword and a constant anxiety about the bomb falling into the ‘wrong hands’ an unceasing worry in geopolitics.

Over the decades, what has largely been forgotten is that the harnessing of nuclear energy was an unparalleled scientific achievement in itself and brought together some of the finest minds of that era.

One of the earliest published accounts of the Manhattan Project, the research and development site based in Los Alamos, New Mexico that produced the first atom bomb, was Robert Jungk’s Brighter Than A Thousand Suns: A Personal History of the Atomic Scientists.

First published in 1956, Jungk was, as he writes in the introduction, attempting to provide “a factual account of the atomic scientists’ tragedy based on their own stories and documents”.

He interviewed those involved, piecing together their version of events to not only tell the story of the bomb but of the tumultuous decades preceding it.

Jungk was born in Berlin in 1913. He grew up a pacifist in a milieu that encouraged militarism, running away first to Paris to study and then to Switzerland to work as a reporter. He wrote about the Nazi war atrocities and the Nuremberg trials but subsequent to the war, his energies were increasingly focussed on the evolution of a nuclear-armed world and its implications.

While Brighter Than A Thousand Suns was about the making of the bomb, Children of the Ashes (1958) was written after a visit to Hiroshima to investigate the aftermath of that bomb. Jungk remained a lifelong campaigner against nuclear energy, winning the Alternative Nobel in 1986.

Brighter Than A Thousand Suns fell into disrepute over the years; some of its conclusions were found to be erroneous while some of the interviewees alleged that they were misquoted.

It was one of Jungk’s premise that the German nuclear physicists serving the Third Reich had more of a moral conscience than their counterparts in liberal democracies. It was the former’s ‘passivity’ that led to the Germans not beating everyone else to the bomb.

Jungk later accused Carl von Weizsäcker of deliberately misleading him on that account. Leslie Groves, from the US Army Corps of Engineers who directed the Manhattan Project (and to whom Jungk attributed the statement describing the project as “the largest collection of crackpots ever seen”) accused Jungk of misrepresentation and falsifying quotes.

His interpretations of the Copenhagen meeting between Niels Bohr and Werner Heisenberg as well as Klaus Fuchs’s espionage have also been refuted over time.

Deconstructed by the wisdom that hindsight offers, what is there in Brighter Than A Thousand Suns to make an average reader pick up a copy of the book? For one, Jungk provides a lively, inspiring account of the years that saw the growth and maturing of nuclear physics.

For young students, especially those on the verge of embarking on a career in science, it paints a picture of the trials that science inflicts on its worshipers and the sweetness of its rewards.

There are evocative descriptions of places and people: of Gottingen in the 1920s, the university town with its half-timbered houses where even retired professors were treated like royalty. Or a young J Robert Oppenheimer walking its streets late at night while reciting Dante or a Wolfgang Pauli dancing on a busy Munich thoroughfare because a new idea had just occurred to him.

It provides perspective on the intersections between politics and science, reminding us that the neutron was being discovered even as the National Socialists were gaining momentum.

But the most important lesson is provided by the stories of the scientists themselves, whether it is the Jewish professors being purged out of German universities or foreign Communist scientists travelling to the Soviet Union only to face fresh purges there.

It dispels the notion of the scientist as a distant and aloof solver of equations and exposes him as one as vulnerable to the vagaries of politics as the rest of us but whose moral choices and compulsions have far-reaching effect on the future of humanity.