Bringing India’s Ancient Water Management Systems To Life

Baolis as symbol of India’s rich architectural heritage have caught attention in recent times, and as a result, many of them have been restored or are in the process of restoration.

Recently-published book, The Vanishing Stepwells of India by Victoria Lautman, is one of its kind in tracing relics of more than 200 stepwells or baolis as they are known in some parts of the country. The book came about after some initial hesitation as Lautman felt that it would be “extremely difficult for me to synthesise what little solid information exists on the topic”.

But two things finally convinced her to write a book, “I’d spent years travelling throughout India, eventually seeing about 200 of these incomparable structures, and I wanted to do more than just look through the photos for my own pleasure. More importantly, it was the fact that how little-known these stepwells are to the world at large that convinced me a book was the best way to raise awareness, since it still drives me crazy that they don't appear on the architectural time-line. The more people know of them, the better their chances of survival, and they’ll be recognised as important contributions to architectural history. Not to mention Indian history."

So, what exactly are these structures that continue to fascinate people from across the world?

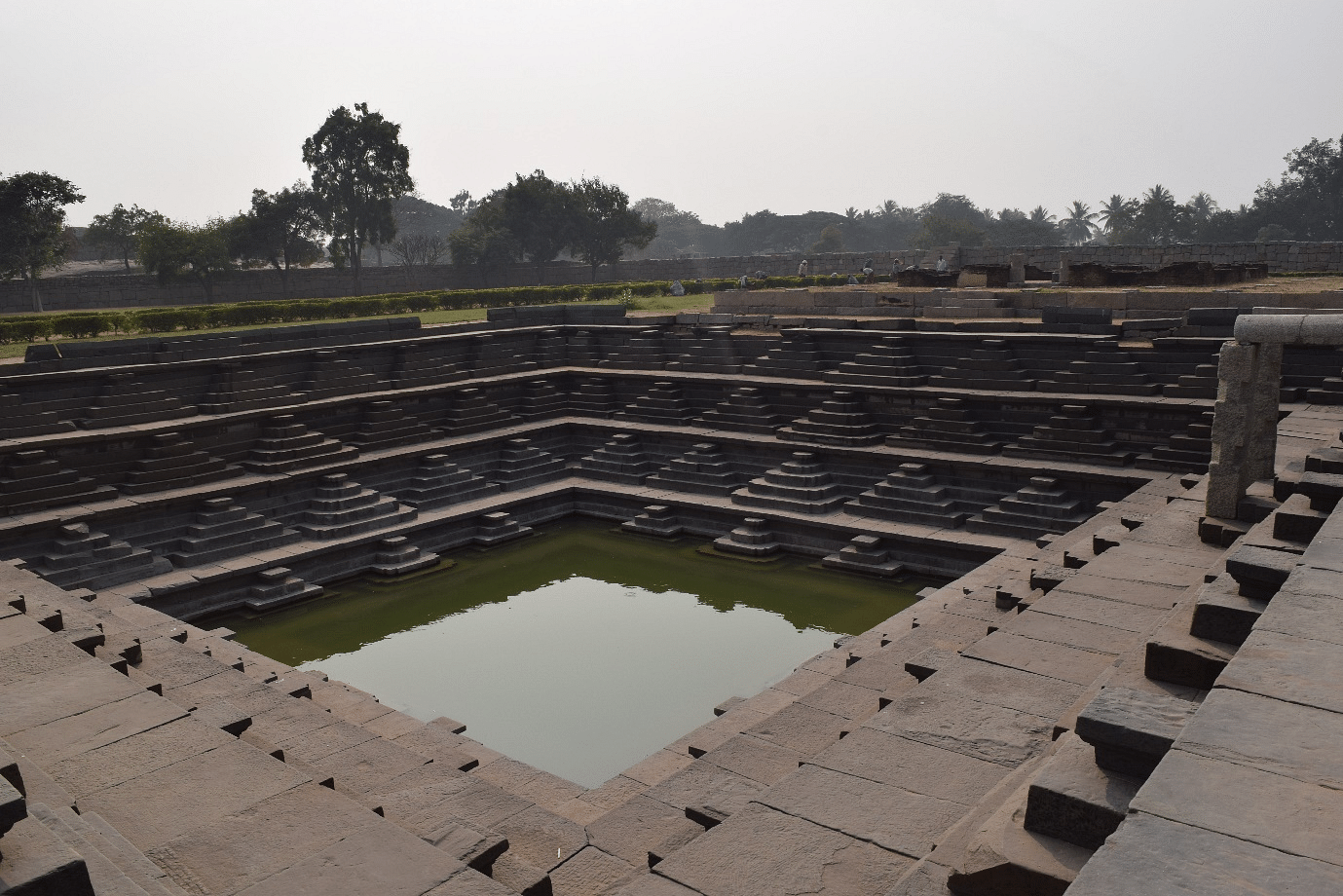

Stepwells, known as baolis, bawadis or vav, have been in use in India since ancient times to manage ground water and rain water resources. A baoli (or a water tank) typically is like an inverted multi-storey structure, descending underground to reach water source. A stepwell may reach six to 10 storeys on an average. These structures were an indigenous answer to the water shortage problem in hot and arid regions of India, especially western parts of the country, where temperatures may reach up to 50 degrees centigrade. Average rainfall in states like Gujarat and Rajasthan is under 100 mm and evaporation may be as high as 78 per cent. In such conditions, water is key to survival and came to be considered sacred.

Over the years, baolis developed in varied sizes and designs, mostly influenced by local conditions. The underground structures are of varied shapes (T, I, U, Z in plan), with steps and numerous pavilions, and rest rooms dedicated to figures of deities. The sunlight diminishes as one approaches the garbagriha; the inner most sanctum and the source of water, generally dedicated to the principal deity. Water can be drawn by either stepping down the stairs or through a pulley system at the ground level. As the water level varies according to season and rainfall, different levels of steps are either submerged or revealed, adding to both the utility and beauty of the structure.

While baolis may follow similar plans, no two baolis are ever the same. There are differences owing to variations in ground structure as well as a builder’s or patron’s ideas, artistic sensibilities, engineering, economic status etc. They were intelligently built along the natural slope to collect run off, their huge areas acted as catchment for rain water harvesting, compact shape reduced evaporation and steps made access easier.

Most of us may have heard or even seen a baoli, but never paid attention to the details of these amazing structures. Some of them, such as Agrasenki Baoli in Delhi, are famous with tourists and regularly feature in Bollywood movies, owing to their beauty and aesthetics. We often forget about that these structures were much more than just architectural marvels. As water was considered life giving, baolis, slowly came to be associated with and named after local deities or even royal families, who often commissioned such works.

In Gujarat, for example, a goddess called “Varudi Mata” is believed to reside in the stepwells. She is believed to be the goddess of fertility. In addition to being places of worship, these great subterranean water structures often were also build along major trade routes to provide the travellers and their animals shelter and water on their journey.

According to Lautman, baolis were “most multi-functional structures of their day. Besides, their primary purpose of providing water year-round, many were important subterranean temples and pilgrimage sites, while others could be retreats. Socially, they were of particular importance to women, who led constrained lives, and the arduous daily task of retrieving water was surely relieved by the communal, congenial gathering at the local stepwell. Stepwells were also visible acts of civic philanthropy on behalf of their patrons, wealthy or royal individuals, who donated the costly structures for the benefit of their community. Interestingly, it is believed that perhaps a quarter of stepwells were commissioned by women, often to honour deceased husbands. So, providing water was just one aspect of a stepwell’s significance."

Thus, a stepwell provides something for everybody. Lautman highlights what attracted her interest in the structures, “every aspect of stepwells is of interest to me – historically, socially, stylistically and anything else you can think of, including their slow slide into general oblivion. But from a purely architectural and engineering standpoint, they are astonishing. When we consider the work that went into excavating these subterranean structures when the available pre-industrial 'tools' were essentially oxen, shovels and sheer manpower, it just boggles the mind. The physical stresses of building into the earth are greater – and more dangerous – than building above ground. Stylistically and artistically, stepwells are endlessly fascinating, no two identical, as unique as fingerprints, whether simple and utilitarian or enormous and ornamented. Adding to that, the physical and psychological experience of being in a stepwell is extremely powerful, not something we are accustomed to. And also, for me personally, it’s the experience of looking down into architecture rather than up at it that disoriented and excited me, presenting something entirely new. My first encounter was profound on so many levels, it's no wonder I became obsessed.”

Stepwells, however, fell out of use during the eighteenth and ninteenth century especially after British took over India. Heritage enthusiast and founder of Youth for Heritage Foundation, Vikramjit Singh Rooprai, sheds some light on the matter, "they (British) felt that these baolis are very unhygienic and should not be allowed. They thought that the water tank contains stagnant water and is prone to getting dirty. Besides, they saw people bathing and washing in water tank and since same water is connected with the well, they were scared of using that water.

When British came to India, most of them became sick due to malaria and diarrhoea. They blamed baolis for mosquito breeding and water-borne diseases. What they did not realise that in a baoli, drinking water is taken from the well and bathing is done in tank. Both are separate and dirty water from tank never goes into the well due to difference in surface pressure over both. Water that comes in well is far cleaner than river because it is filtered by sand. The British established the water management system, where drinking water was taken out of river and cleaned chemically. This gave birth to countless problems as baolis and wells became useless now. The secret of baolis and wells remaining clean was that their water was circulating regularly. Slowly, most of them started drying up and many got filled with earth”.

Baolis as symbol of India’s rich architectural heritage have caught attention in recent times, and as a result, many of them have been restored or are in the process of restoration. Dr Swapna Liddle, convenor of the Delhi Chapter of Indian National Trust for Arts and Cultural Heritage, highlights the successful restoration of Hazrat Nizamuddin Baoli in Delhi. The baoli is one of the last few surviving stepwells of Delhi, built in 1321-22 by Sufi saint Hazrat Nizamuddin Auliya. However, due to encroachments along the baoli, muck and sewage had polluted the waters. The baoli has been restored to its former glory through the efforts of Aga Khan Development Network, which restored and developed the baoli as part of their Nizamuddin Urban Renewal Initiative. The baoli now forms an integral part of the adjoining dargah and is part of bustling social and religious activities.

However, it may not be always possible to revive the water management system of these structures. According to Rooprai, “it is very unlikely that these subterranean structures can be revived. A baoli or a well needs proper water table and catchment area around the structure, through which water can reach the underground aquifer. With expanding concrete jungle and carpeted roads, we are not left with adequate catchment areas. Besides, the secret is to use the water regularly. Since we have an alternate water management system, these baolis will be of no use, unless we connect them to our present water system." While it may not be possible for us to restore the water system (at least not for all), the beautiful structure of the baolis may be put to adaptive reuse. According to Dr Liddle, “even if it is not possible to restore water in all stepwells, they can be used for new functions. Some of them would make spectacular settings for performances or even as open-air art galleries."

Reviving baolis can be difficult but not impossible. We have many examples of such revival, where totally dead baolis were put to use and given back to the community as a shared resource such as Nizamuddin Baoli. Another case is of Toorji Ka Jhalra in Jodhpur revived as part of JDH Urban Regeneration Project. The stepwell system is an example of what can be achieved through people’s participation and cooperation among government agencies. The stepwell was filled to ground level with filthy and stagnant water. This was pumped out on a 24-hour cycle for several months, thereby revealing several levels of a stepwell that had been buried for years. The place was finally revived and is now used by locals as a cool shelter against the brutal heat. The complex also houses a cafe that has become popular with tourists for it provides a view of the stepwell.

Given the declining water table at most places in India, these structures can be put to use for recharging ground aquifers and harvesting surface runoff. Three major aspects should be kept in mind while reviving these structures:

- Draw local level strategies to prevent destruction of baolis and ensure that extraction of the ground water does not exceed recharge of aquifers.

- Invest in surface water systems and harvesting the rainwater to rebuild the ground water reserves by reviving these community water structures and keeping them unpolluted.

- Heritage conservation and change to revive baolis as platforms for sharing public life, spreading ecological awareness and allowing enhanced experience for both the residents and visitors.