….But What Exactly Is Your Dharma?

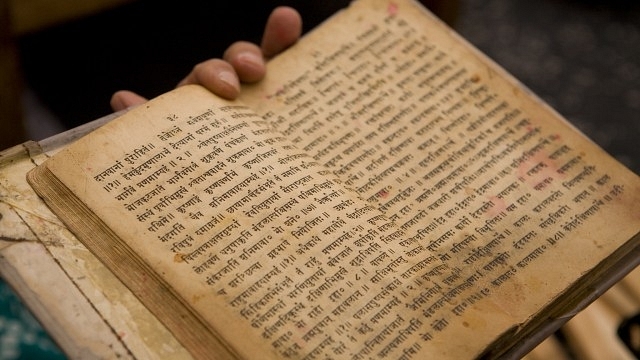

To understand what differentiates HInduism from Western religions it is important to understand what dharma means. R Ganesh’s book is a good place to start.

A review of ‘Your dharma and mine’ by Dr. R Ganesh; translated from the Kannada by Hari Ravikumar.

No greater error arising from Indology has diminished Hinduism and contemporary Indian society more than the one etymologically reducing the idea of dharma as equivalent to the Semitic concept of ‘religion’ and consequently, dharma-nirpeksha (neutrality towards dharma) as ‘secularism’.

The essential attributes of Western religion; the centrality of a patriarchal god, a (male) human as prophet who is the divinely ordained recipient of revelation which is a unique historical event in time with absolutely no future possibility of its verification or replication by any other man, theological permanence in monotheism and a divine moral and legal code with no scope for transgression among believers are largely absent in the Hindu way of thinking while conceptualizing the universal order. (For instance, the theological impermanence and diversity of Hinduism is illustrated in the evolution of cults of various gods and goddesses and their changing stature through the course of history)

This fallacy has been brilliantly deconstructed by S N Balagangadhara in his seminal work, ‘The heathen in his blindness’ where he argues that “if the Semitic religions are what religions are, other cultures do not have religions. If other cultures have religions, then the Semitic religions are not religious. The inconsistency lies in insisting that both statements are true.”

The recognition of Hinduism as distinct from Semitic ‘religion’ necessitates discovering the roots of dharma which in turn constitutes the foundational basis of Hinduism.

The Sanskrit word ‘dharma’ is derived from the root ‘dhr-dharane’ or that which upholds or sustains. Indian philosophical schools whether Vedic or Non Vedic have contributed in developing the principles of dharma as represented in ancient Indian law, conduct, morality, ethics and spirituality (struggle for moksha). Dharma is viewed in Hindu texts as means for protecting the weak against oppression by the strong.

The author points out that several kinds of dharma are described in the Smriti and Samhita texts including the Mahabharata and Manu Smriti; raja dharma for kings, apad dharma for emergencies, moksa dharma for salvation, visesa dharma (for specific people in particular social positions) and samanya dharma which applies to everyone at all times.

This book contains a short exposition of this samanya dharma whose appeal lies in its universality. Its principles according to Medhatiti, the celebrated commentator on Manu are applicable to ‘all humans, irrespective of occupation, gender, nationality or education’. The author locates several valuable references to samanya dharma in a variety of Samhita texts. The traits describing samanya dharma in the Manu Smriti (7.92) include courage, forbearance, self-control, abstinence from sealing, control over senses, power of discernment, self-knowledge, integrity and freedom from anger.

The Vishnu Smriti (2.26-27) also includes the traits of ‘freedom from despair and miserliness, freedom from jealousy, respect of gods and sages’. Interestingly, the Mahabharata often recognizes samanya dharma as sanatana dharma with characteristic traits of non-injury, truth, freedom from anger and charity (13.147.22).

Further, Sanatana Dharma is described as ‘Not to trouble any living creature in thought, in speech or in action; to be considerate towards everyone and to respect, nurture and protect all forms of creation’ (12.162.21). The author further informs us that it is in the Gautama Dharma sutras that the concept of samanya dharma are crystallized as the eight atma gunas (‘fundamental human traits’) which include ‘compassion towards all beings, forbearance, freedom from envy, cleanliness, freedom from over exertion, auspiciousness, freedom from misery and freedom from greed’ (1.8.24).

The author provides penetrative insights into each of these atma gunas. To instantiate, cleanliness is not just personal hygiene and external environment but also relates to the inner world. The concept of anayasa or freedom from over exertion due to physical or mental trauma probably anticipates modern conceptions of respect and dignity for labour.

We may like to ask, how does the concept of Samanya dharma comparatively relate to Semitic religious norms for appropriate behaviour?

Among the ten commandments of the Bible, there are similar declarations pronouncing prohibition against stealing, killing and lying although they are superseded by the manifest need to maintain belief in only the one true god who will not tolerate the worship of any other gods and neither idolatry.

In our view, what ultimately differentiates the Hindu concept of samanya dharma as opposed to the purely ethical elements of the biblical commandments is the positive conception of the former as a practice adequate for attainment of the state of liberation by the householder. In the same spirit, the Vasista Dharma Sutra states that ‘good conduct is imperative if actions inspired by Vedas and other good deeds have to attain fruition’.

The ingenuity of the author is vested in his conviction that principles of dharma are universal and discoverable in all holy books and belief systems, irrespective of their allegiance to the Vedas, in the form of ‘something that guides everyone on the right path, a fundamental principle, a nourishing elixir and a strong support.’

This urge of subsuming all beliefs systems within the ambit of dharma stems from the Neovedantic “All Religions are true” fallacy. The problem with using vague words like ‘right path’ or ‘fundamental principle’ arises when encountering the irreconcilable among those religions which believe their path to be the only true way while associated with intolerant ideas of hellfire and eternal damnation for disbelievers and those which affirm the legitimacy of multiple paths to perfection.

Secondly, the author makes a plea to include materialistic atheism within the vast dimensions of dharma since ‘absence of belief in moksha’ does not repudiate the place of dharma as an ‘essential’ ‘device’ in the life of an atheist who aspires for kama (sensual desires) and artha (wealth and economic prosperity).

Yet, the facts of the world suggest that kama and artha can be earned by the unrighteous pursing all that which is against dharma. In effect, the need for dharma to guide the acquisition of kama and artha is apparently rendered superfluous in the absence of belief in an overarching goal of moksha which is lacking in materialistic ways of living.

The author suggests that on the contrary this is not so since those who don’t believe in moksha may avail of concepts like ‘humanity, decorum, sincerity and working in harmony with the natural laws’ which constitute their preferred idea of dharma.

Finally, the author desists from engaging in the debate on criticism directed against the dharma samhitas for discriminating against shudras and women. For a work which cites copiously from the Manu Smriti such an omission could have been avoided.

All in all, this is an excellent exposition on the neglected topic of samanya dharma and deserves wide readership.