Caste is Hardly an Impediment for ‘Homecoming Hindus’

The question is a valid one. But the answer is simple, if one is aware of the social history of conversion and reconversion and the Hindu texts dealing with these matters.

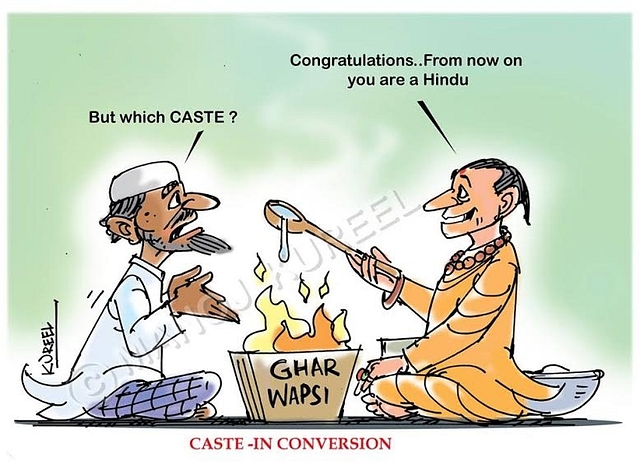

What caste do ‘homecoming’ Hindus go to? A natural and valid question in the light of the ongoing debate on ‘homecoming’ (ghar vapsi) ceremonies, which refer to the process of reconverting Indians once believed to have converted from Hinduism to Islam and Christianity. But it is asked in a chastising and ridiculing tone, instead of as a genuine matter of enquiry. Even the otherwise creative and well-meaning cartoonist Manoj Kureel expresses this as a chuckle in one of his recent cartoons.

The chuckle comes from the poor sense of social history that most Indians have. This results in some simplistic and pedestrian notions: that only Hindus have castes, and Indian Christians and Muslims do not have any caste or social categories; that returning to Hinduism is a novelty, a new and unusual thing that the Sangh Parivar is unleashing! Are they caught off guard on the caste question?

Both notions are baseless.

Let us take the first notion. Most Indian Christians have their caste identities well-known; many even flaunt it or make it part of their surnames. In many cases, the Christians have affinity and close contacts with Hindu members of the same caste, which is cunningly exploited for evangelism and gaining more converts from the same caste group.

Even in cases where an entire region got Christianised, like the fishing communities of the southern coastal districts of Tamil Nadu, they can easily trace their ancestry back to the level of sub-castes, as there are Hindu Parathavar communities still living in the neighbouring fishing regions. Even in the case of Anglo-Indians or highly urbanised Christians, the caste can be very easily traced, with some ancestral memory of just one or two generations.

In case of Indian Muslims, the caste groups have evolved over a much longer period with regional variations. With some exceptions of high caste and aristocratic Muslims tracing their ancestry to Arab, Persian or Turkish countries, all Indian Muslim castes can find their parallels in the Hindu castes of their native region.

We have Rajput Muslims transcending national borders in both India and Pakistan, and Kashmiri Muslims with surnames like Bhat, a pan-Indian priestly Brahmin caste name. Even social groups like the Julahas (weavers) of UP or some artisan communities of West Bengal with all their members as Muslims have their equivalent Hindu castes living in the same or nearby areas.

Now, let us test the second notion. There is a very long history of assimilation and reconversion into Hinduism. In some sense, it even predates Islamic invasion of India, when our ancestors assimilated many aliens like Greeks, Kushanas, Shakas, Tartars and Baluchis into the Hindu fold. The Puranas, as well as historical sources, confirm this. Rites like vratyastoma were specifically adapted for this purpose.

Even after centuries of Islamic rule in the north Indian hinterland, conversions to Islam were far from being total and complete, as people and groups were returning to their mother religion, whenever opportunities surfaced. The Bhakti movement, accentuated by sadhus, saints and reformers provided an impetus to this. Many historians who wrote on the medieval period, like K.S. Lal and M.A. Khan, have pointed out this fact.

A text Devala Smriti (dated to 10th century AD) arose at a time in history when Sindh was fully conquered by Muslims and their armies were advancing into the inner regions of India. It contains rules and regulations for assimilating back those who were forcibly pushed into the mlechchha (alien, obvious reference to Muslims) fold. It prescribes purification rites for them. It also lays down guidelines for fully accepting and rehabilitating women who were carried away in raids and siege by Muslim armies and later rescued, even if the women had conceived or borne children because of rapes by the captors.

The liberal and humanistic outlook of Devala Smriti in this regard, given the established views about chastity and honour of those periods, is indeed surprising and commendable. Such an outlook is something that cannot be imagined even in today’s India. Perhaps it is the sheer question of survival in those hard times that made the Hindu orthodoxy take such a stand. Some other Hindu law books of the medieval periods, like Vignaneswara’s commentary to Yagyavalkya Smriti also corroborate this.

There is evidence to establish that such guidelines were not just written down, but actually followed, even in south India. D.R. Bhandarkar quotes an incident in 1398-99 CE during the Vijayanagara era, in which 2,000 Brahmin girls of a village were rescued from the armies of Firoz Shah Bahmani and accepted after purification rites [1].

As per popular legends of the region, Bukka Raya, one of the founders of the Vijayanagara empire, was himself a reconverted Hindu; he had earlier been forcibly converted to Islam. In a divine twist of history, it was this empire that acted as a shield to arrest further Muslim expansion into the south, and reclaimed the Hindu holy sites of Srirangam and Madurai from Muslim captors.

There is sufficient evidence to conclude that much more of such reconversions to Hinduism must have happened with the fall of the Mughal Empire and rise of the Marathas and Sikhs. The Shuddhi movement of Arya Samaj, carried to many parts of the north in the early decades of 1900s by Swami Shraddhananda, is nothing but a continuation of this long-time Hindu practice. The movement was broad and all-encompassing. It also included a fierce campaign for removal of untouchability and emancipation of depressed classes and received praise from none other than B.R. Ambedkar.

So, what castes did the Hindu reconverts go to during all this time? In most cases, their earlier castes, even if that caste was lower in the hierarchy of those times, because it provided them social cohesion and protection. In some cases, they formed new caste groups which, over time, merged with allied larger castes. This is what Swami Vivekananda said in an interview that appeared in Prabuddha Bharata, April 1899 [2] . In the words of the interviewer:

“I want to see you, Swami,” I began, “on this matter of receiving back into Hinduism those who have been perverted from it. Is it your opinion that they should be received?”

“Certainly,” said the Swami, “they can and ought to be taken.”

He sat gravely for a moment, thinking, and then resumed. “Besides,” he said, “we shall otherwise decrease in numbers…and then every man going out of the Hindu pale is not only a man less, but an enemy the more…The vast majority of Hindu perverts to Islam and Christianity are perverts by the sword, or the descendants of these. It would be obviously unfair to subject these to disabilities of any kind…Why, born aliens have been converted in the past by crowds, and the process is still going on…”

“But of what caste would these people be, Swamiji?” I ventured to ask. “They must have some, or they can never be assimilated into the great body of Hindus. Where shall we look for their rightful place?”

“Returning converts”, said the Swami quietly, “will gain their own castes, of course. And new people will make theirs. You will remember,” he added, “that this has already been done in the case of Vaishnavism. Converts from different castes and aliens were all able to combine under that flag and form a caste by themselves—and a very respectable one too. From Râmânuja down to Chaitanya of Bengal, all great Vaishnava teachers have done the same…”

In a broad historical perspective, we can say that Hinduism successfully reclaimed a sizable chunk of its adherents who were forcefully converted to Islam in the Indian mainland, thanks to the rise and consolidation of Hindu political power, and also because of the twin qualities of cohesion as well as flexibility in its caste structures.

But due to the lack of Hindu political power, it could not do this in frontier areas of present-day Pakistan and Bangladesh or in the faraway islands of Indonesia and Malaysia, which once were seats of Hindu culture. The renewed interest and zeal in the reconversion ceremonies should be viewed as a continuation of the historical process of Hindus reclaiming their lost heritage in the Indian mainland.

The metamorphosis that caste has undergone in the current socio-political climate is an altogether different topic that needs to be discussed separately. Casteism and any form of caste-based discrimination are social evils that every Indian should strive to remove, from our individual lives as well as public spaces. But what we can clearly see is that caste is hardly an impediment or hurdle for ‘homecoming Hindus’ in the 21st century.

References: