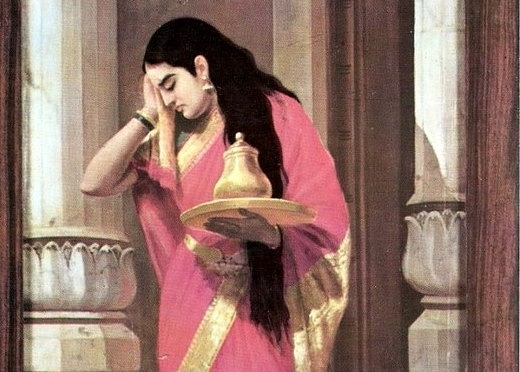

ENOUGH: Draupadi, Let Us Be You

The Kauravas insulted and tried to strip Draupadi in the Dice Game. What we have is not only despair and anger, but also hope, and finally a line, drawn. Here. And now.

A long time ago, Vyasa wrote an epic called the Mahabharata. For reasons mostly vague, the story often remains a specific comment not only about the times that the epic was attributed to, but strangely also in today’s context.

Given the fact that it is a fascinating tale of a family that sees intrigue, guile, scheming, manipulations and wisdom besides much more, it is perhaps hardly surprising that it never goes out of fashion.

Covering perhaps the entire spectrum of emotions that humankind is associated with, the Mahabharata manages to remain unfailingly relevant even in times as different—or, who knows?—maybe as similar. The recent debate about whether the Gita should be made the national scripture is a case in point.

Even while I write this, there are reports of a woman being raped in India’s capital city by a driver from a well-known internet platform that provides, among other things, cab service. Much to everyone’s relief, the services of the particular company have been banned by the government in Delhi—states have been advised to follow suit—amidst public outrage at the incident.

As is the case after every such crime, there is a plethora of opinions floating around. I met a few friends, and one suggested rather passionately that women in Delhi should be allowed to carry arms, the knowledge of which would keep potential rapists at bay.

Even before some of us begin to scoff at the idea and how dangerous it can be if misused, a male friend angrily interjects saying knee-jerk reactions would only mean that feminist groups would begin asking for far more stringent laws as well as armed escorts from corporate houses for their female employees, which in turn would make corporate houses think twice before hiring women candidates since it would mean additional expenses for them.

While the premise of this argument lies in trying to prove that rape is a social crime and should be dealt perhaps like all other such crimes are in India (read: with immense patience towards the rapist and apathy for the victim). The question remains: Does a large part of India still think that ensuring female safety is actually still an either-or proposition that calls for further debate and permission from those who feel so inclined to, once in a while, benignly grant us some free space for manoeuvre, where some safety precautions related to women are doled out, and all is considered hunky dory?

For a moment I’m taken back to the historic dice-playing session in the Mahabharata, where Draupadi is dragged into the arena where her eldest husband sits betting and losing not only his kingdom but also his wife who, for some reason, is seen as a property that can be lost at a game of dice.

But of course that is not all.Her five husbands, all of whom are renowned warriors, don’t raise a finger to save her and she is left to plead for mercy and divine intervention in order to save her dignity.

The Mahabharata is a mix of emotions, of disquiet, a poetry often so sublime that, in many instances, even today its profound impact on our land and its people is still palpable. No one here names a son born in the family Duryodhana, nor does anyone name the daughter Draupadi—the unfortunate woman who has been described as ‘a woman who is neither too short, nor too tall, neither pale nor dark; she is earth’s most perfect creation and the pole of all men’s desire’. With scorn in her eyes and anger in every fibre of her being, Draupadi refuses to tie or oil her hair till the time she is avenged of her humiliation at the hands of the Kauravas who have tried to disrobe her. She will tie her hair only when she can bathe it in the blood of Dushasana, who tried to disrobe her.

Bhima brings her Dushasana’s blood after he had killed him. Draupadi ties her hair up.

How one looks at women in our country, while associating certain imagery with them, might have changed through different periods in history.

It is still fascinating to try to understand the journey from the fresh perspective of an outsider at times. Scriptwriter of the pathbreaking—and truly globally representative—theatre experiment of The Mahabharata by Peter Brook, Jean-Claude Carrière, in his book In Search Of The Mahabharata: Notes of Travels in India with Peter Brook describes a particular meeting with former Bharatnatyam exponent Rukmini Devi when she was all of 80. He writes:

Before meeting Rukmini Arundale who had agreed to receive us, I asked a man who knew her,

‘What is she like?’ ‘She is very beautiful’, he answered. Over here, one rarely describes a young woman as beautiful. She is ‘pretty’, ‘nice looking’, ‘attractive’ but very rarely ‘beautiful’. It seems that beauty is a quality that is acquired.”

Monsieur Carrière sees mystique as a large part of who the Indian woman is. While in Calcutta watching plays based on the stories of the Mahabharata, he notices young women in the audience eyeing the outsiders.

He says, while this would be considered an invitation by Western standards, here that is not the case: ‘Here one makes love only with the eyes.”

The description makes me think how our perception of womanhood, often based on our cultural edifices, seamlessly coincides with that of our realities. What is a mere representation of womanhood in a cultural subtext to an outsider is often the hard truth that shapes our lives in (the) subcontinent.

Where reality takes off, when the play has ceased to be is rather difficult to identify especially when it comes to our own understanding and interpretation of the subtext of the epic. If Draupadi is insulted and disrobed in a room full of men and women, all of whom are supposedly wise in their own right, neither are the other women characters in the epic spared.

Kunti has to let go of her first born Karna and has to live the life of a widow because her husband chooses to lustfully touch his other wife in spite of knowing that he could die and leave his newborn sons and Kunti to a lifelong fate of misery.

Amba is spurned by her lover, once Bhishma wins her over by force as his brother’s wife and she remains lonely and angry lifelong as a result of that one action of Bhishma, and finally commits self-immolation to exact revenge on her tormentor in the next birth.

Other lesser known female characters like Sudeshna, Madayantika, who are devoid of any freedom whatsoever, are portrayed as mere puppets that have to agree to intimate physicality with any man imposed upon them by men of influence, including their husbands. Gandhari sacrifices her sight for a husband who is driven by jealousy of his brother and his sons that finally results in the killing of all of Gandhari’s sons.

The only son of Dhritahshtra, Gandhari’s husband, who survived the Krukshetra war, was his illegimitimate (if we may be allowed to use that term). Juyjutsa, who fought on the Pandavas’ side.

Nandalal Bose, whose works were often a conscious extension of nation building, had painted Gandhari with a blindfold sitting in what appears to be a balcony with a maid who is perhaps describing to her the scene outside.

In many ways the painting is not only a depiction of her sacrifice but also her helpless dependency on others. One wonders whether it is perhaps time for us to interpret these messages from the epics in a context befitting today’s disturbed milieu.

Fortunately though, not all our literature and corresponding history show women without a mind and, though the general thought process adheres to the belief that ‘women and jewels are common property’, as reiterated by what Jayadrata says to Draupadi, there are specific instances where the trend is delightfully reversed.

A reading of Prakrit poetry from the second century CE compiled under the anthology Gathasaptasati is a revelation about women who are open about their sexuality, feelings and other such desires:

At night, cheeks blushed

With joy, making me do

A hundred things,

And in the morning too shy

To even look up, I don’t believe

It’s the same woman.

The Absent Traveller. Poem number 23

Today one assumes times have changed, the subaltern has finally spoken, the State and its people are well aware and, by that notion, have not only enabled their women with adequate means to protect themselves but also in various other ways have shown that they care. But little has changed, because in the end rape is a power game that seeks to establish more than the obvious assertion of the masculine.

Having said that, despondency is perhaps not the road that needs to be travelled now. There are men and women, creatures of hope and some anger, who refuse to believe that things can only get worse. Can I again quote from the Mahabharata, its revelations as described in the ‘lake scene’ in Peter Brook’s version, which holds good for all of mankind devoid of gender classifications?

The Lake: What is the cause of the world?

Yudhishtira: Love

The Lake: And what for each of us is inevitable?

Yudhishtira: Happiness

As if by the same poetic justice, I see an image doing the rounds on my buzz feed where the prime accused rapist Shiv Kumar Yadav is being led to custody by a wel known name, lady police officer SSP Manzil Saini, who has already proved her credentials. Officer Manzil has no nonsense written all over her face, even as she escorts the accused away from the media scrutiny, her left hand raised in decisive authority that could be well interpreted as ‘this much and no more’.