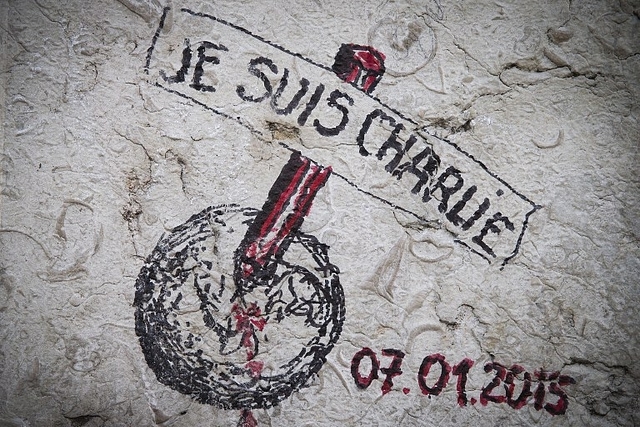

Freedom Of Expression Meaningless Without Right To Offend

Extracts from There Is No Such Thing As Hate Speech: A Case for Absolute Freedom of Expression by Ravi Shanker Kapoor

There Is No Such Thing As Hate Speech: A Case for Absolute Freedom of Expression, Ravi Shanker Kapoor, 2015

Freedom of expression = Right to offend, right to blaspheme

The fear [that absolute freedom of expression can be harmful] has its roots in the belief that there is a reality (or Reality) which can be misrepresented or distorted if the freedom of expression is absolute. This presupposes a universally accepted definition of the reality. But the fact is that no such definition exists; there are as many definitions of reality as there are philosophers and philosophies. There are Christian theologians interpreting the faith in numerous ways; there are six orthodox Hindu schools of philosophy, with several sub-schools; there are Marxists again following countless lines; there are Western conservatives (all of them ardently anti-state, Burkeans in harmony with tradition); there are libertarians (followers of Ayn Rand and others); there are postmodern thinkers who actually do not believe in any reality. It is a long list. What then is the reality or ultimate reality? What is the truth or the Truth?

… My assertion is that since there is no universally accepted understanding of (ultimate) reality, the question of its misrepresentation or distortion does not arise.

Let us come down from the metaphysical plane and concentrate on the mundane aspects of life. Let us discuss topics like the state, market, society, individual rights, and property. Again, we face the same plurality of views. What is the state? Marxists define the term in a way with which libertarians and conservatives can never agree with. What should be the role of the state? While Left-leaning thinkers would argue for its greater role in the economy, libertarians and conservatives would like it to keep away from the market…

What is society? Is it organic and more than the sum-total of individuals as Burke and many conservatives believe? Is society, as Burke put it, “a partnership not only between those who are living, but between those who are living, those who are dead, and those who are to be born”? Rand would disagree with such a definition of society; in her scheme of things, everything is subservient to the individual and his rights. Interestingly, both Burke and Rand are placed on the right of the ideological spectrum.

Individual rights are also understood in vastly different ways by thinkers of different persuasions…

Similarly, on property there are diametrically opposite views across the ideological spectrum…

Therefore, there is no unanimity on any kind of reality, metaphysical or mundane. I will reiterate that this is not a thesis promoting epistemological nihilism; on the contrary, mine is an attempt to undermine such nihilism. This nihilism is actually promoted by the postmodern dogma in association with various anti-Enlightenment tendencies like political correctness, multiculturalism, and Islamism.

The only way we can know any truth is by allowing the free play of ideas in the arena of public discourse, a veritable laissez faire. A genuine quest for knowledge and a yearning for wisdom (or philosophy, which is etymologically, “love for wisdom”) is an onward march to gain more facts; we shall realize as many truths as possible. The quest may or may not lead us to the “Ultimate Reality” (if it exists), but we can hope to approach it. However, this march is impossible without unrestrained freedom of expression.

And if there is no consensus even among the greatest philosophers about the nature of any kind of reality, it is the apogee of hubris, and dirigisme, to assume that politicians, bureaucrats, and judges know what the reality is and what its distortion…

The Galileo affair needs special mention in the context of the Offence Principle… Had Galileo decided not to offend the Christians—and this would have been a rewarding option—he would have deprived the world of important truths and science would have been poorer. He was not granted freedom of expression; he had to grab it. And he did offend many—and suffered because of the “offence.” Without the freedom to offend, as Salman Rushdie said, freedom of expression ceases to exist.

Hurting the sentiments

Let’s look at the real questions—how valid are the demands based on hurt sentiments and how legitimate are the grounds on which various works have been banned—from a legal point of view…

“Reasonable restrictions” appended to the Right to Freedom of Speech and Expression in Article 19 (a) empowered the State to curb this Fundamental Right whenever it wished to. Restrictions can be imposed for the maintenance of “the security of the State, friendly relations with foreign States, public order, decency or morality, or in relation to contempt of court, defamation or incitement to an offence.”

Even as these restrictions are an affront to democracy, these are themselves purported to be “reasonable.” In other words, these can be imposed only if there are reasonable grounds for harming national security, jeopardizing friendly relations with foreign countries, disturbing public order, offending decency or morality, contemning court, leading to defamation or occasioning incitement to an offence. Nowhere is it mentioned that hurting the sentiments of somebody can be a ground for curtailment of the freedom of expression.

The grounds restricting the freedom of expression have to be reasonable and not sentimental, not only because it is the Constitutional position but also because reasons can be objectively debated, while sentiments can’t be. Merriam Webster describes “sentiment” as “an attitude, thought, or judgment prompted by feeling”, “predilection”, “a specific view or notion”, “opinion”, “an idea colored by emotion”, etc. It is crystal clear that the defining feature of sentiments is subjectivity.

The law and public administration, on the other hand, are molded by objective realities. Poetry is to sentiments and subjectivity what political philosophy is to statecraft, jurisprudence, and objectivity. Plato said in the Republic that there is an old quarrel between philosophy and poetry. According to him, if poetry is allowed in its ideal state, “not law and the reason of mankind, which by common consent have ever been deemed best, but pleasure and pain will be the rulers in our state.” This was the reason that he banished poets from his ideal state.