Hey Minister, Leave Those Films Alone!

The Gujarati film industry is clear proof that the best way for regional cinema to compete with Bollywood and survive is to raise its game and rely on the wisdom of the consumer, and not through state government aid.

Even as India’s regional film markets continue to be dominated by Tamil and Telegu movies, the Gujarati movie industry has grown by leaps and bounds in the last couple of years. Significant credit for its gradual evolution into one that increasingly caters to modern audiences must undoubtedly go to the intense competitive pressures exerted on Gujarati filmmakers by Bollywood productions.

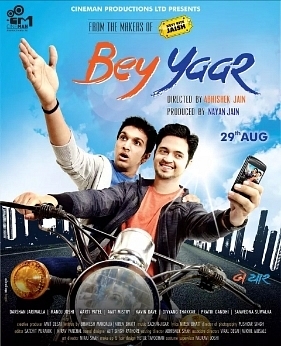

When some of my friends urged me to check out BeyYaar, a recent Gujarati movie that revolves around true friendship, my initial response was one of indifference. I was not particularly excited about spending Rs 150 for regional cinema, which I knew usually produces substandard movies owing to budgetary constraints and an unwillingness of regional producers to innovate.

But this movie took me by surprise. It involved the use of superior movie-making technology, mature comedy, refined cinematography, as many as 50 locations featuring Ahmedabad’s architectural grandeur, and a script relatable to the modern youth – all of which made it comparable to a satisfying Bollywood production.

In 2012, there was another movie called Kevi Rite Jaish (How will you go?), which was a satire on the Gujarati’s fascination with migrating to the United States of America. It grossed handsomely at the box office, eliciting a younger and urban crowd that is otherwise predisposed to watching high-budget Bollywood and Hollywood movies. The movie ran for 17 weeks in multiplexes across Mumbai, Ahmedabad, Vadodara, Rajkot, Anand, as well as overseas in the US, UK, New Zealand, Australia and some Middle Eastern countries.

The sudden resurgence of Gujarati cinema into the mainstream multiplex arena, where one needs to shell out anywhere from Rs 150 to Rs 300 for a movie, made me wonder: what explains this radical transformation? The answer, as we will see, lies in the free market.

Advocates of protectionism (who may broadly fall under the umbrella term ‘swadeshi’) believe that banning foreign products and services boosts indigenous industries as consumers are then forced to buy domestic products. But how feasible is this idea and what would be its implications in the real world?

Let’s hypothesise what would have happened if Gujarat’s government, under pressure from various protectionist lobbies, had banned Bollywood movies from being screened in the state. The pretext for banning “foreign” movies would be that they hurt regional Gujarati producers. As an inevitable consequence, we, the consumers, would have been forced to watch third-grade regional productions, because the film makers would have had zero incentive to innovate.. Alternatively, most consumers would have chosen to import pirated Bollywood movie CDs from Mumbai or elsewhere, fuelling black markets in the process.

But thanks to fierce competition from the continually evolving Bollywood industry, Gujarati filmmakers have been forced to raise their bars. They have adapted their scripts to make the stories relatable to the modern audience, while employing famed Gujarati-speaking Bollywood actors such as Darshan Jariwala (who played Gandhi in Gandhi My Father) by paying them market rates.

Several critics accept the argument for free markets and competition, but suggest that the government should fund regional producers to level the playing field among big budget and small budget movies.

The other day, I read in the news about a regional director lobby blaming “lack of governmental support” for the adverse performance of their movies at the box office. To help their low budget films survive competition from high budget Bollywood productions, they urged authorities to consider providing subsidies, cheap interest rate loans, and grants.

The argument for extending government support to small movie companies looks very tempting on the surface. If only regional producers had more funds, they would be able to cut costs, invest in technology, and make better films. The problem, however, arises when we consider where government funds come from. In Margaret Thatcher’s words, “Let us never forget this fundamental truth: the State has no source of money other than money which people earn themselves. If the State wishes to spend more it can do so only by borrowing your savings or by taxing you more. It is no good thinking that someone else will pay – that ‘someone else’ is you. There is no such thing as public money; there is only taxpayers’ money.”

So whenever we ask the government to subsidise regional moviemakers, or for that matter any other business, we must first ask ourselves: would I be directly willing to loan out or donate my hard-earned money to those businesses? If the answer is no, then asking the State to do it on our behalf comprises hypocritical behaviour.

Another problem with allowing the State to invest (through subsidies, loans, or grants) in movie scripts pertains to the existence of incentives to perform due diligence. Private investors either use their own money or are directly accountable to people whose money they invest. If money managers make poor investments, they would fail to attract any more investors. And so they have significant incentives to rigorously test the workability of an idea before investing.

But the State, by virtue of coercive taxation, has far fewer incentives to perform due diligence and ensure that its investments in movie companies succeed. In case of failure, bureaucrats – unlike private investors – hardly have to fear market retribution in the form of losing future investors.

Additionally, we must also consider costs to other parts of the economy. Using taxpayer money to fund incompetent movie producers means less funds available for competent producers. In other words, it causes misallocation of national monetary resources. This misallocation ends up hurting the entire movie industry, which could otherwise have been served well by the market, free of government interference.

The sterling example of Gujarati cinema can be replicated across other regional film industries merely by keeping the State at a distance. Government has no business to support or create unnecessary policy hindrances in an art, the evolution of which is best left to the free market. Private investors will decide investment-worthy movie scripts after conducting proper due diligence, while the audience will decide, through their demand, which movie idea to reward and which to discourage.

Note: This piece has been modified to correct an error. Darshan Jariwala played Gandhi in Gandhi My Father and not Lage Raho Munnabhai as the earlier version of this piece claim.