How Pakistan’s Zia Handed The Baton Of Bigotry To The Next Generation

In her book Purifying the Land of the Pure: Pakistan’s Religious Minorities, writer-politician Farahnaz Ispahani discusses the choices made by the successors of Muhammad Ali Jinnah that has led to the current state of religious intolerance and persecution of minorities. Edited excerpts:

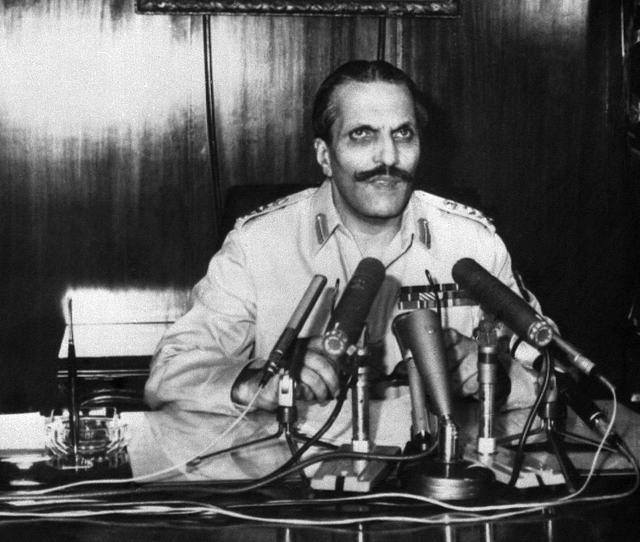

For thirty years after Independence, Pakistanis at least debated the role of Islam in matters of state, even as the political balance gradually shifted against secular and pluralist ideas. Once General Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq seized power through a military coup in 1977, debate was terminated and replaced by arbitrary and forced Islamization. Zia changed laws by decree, imposed draconian punishments based on medieval interpretations of Islam, silenced secular critics and changed school curricula to pass on his bigoted worldview to the next generation.

Hardline clerics with limited followings now preached on national television, and orthodox religious schools (madrasas) proliferated with state and foreign funding. Islamist militias, trained to fight the Communist occupation in Afghanistan, also turned their guns on non-Muslims, Ahmadis and Shias within Pakistan, often with a nod from Zia’s officials and political allies. If the 1947 Partition virtually cleansed Pakistan of Hindus and Sikhs, Zia-ul-Haq’s decade-long dictatorship marked the beginning of a period of heightened sectarian violence, in which all but the most obscurantist Muslim sects and groups were targeted…

…Zia, who used the phrase ‘soldier of Islam’ to describe himself in his very first speech, subsequently insisted that he was a pious Muslim seeking to revive Islamic law as practiced in earlier times. He praised ‘the spirit of Islam’ that had characterized the opposition protests, adding ‘It proves that Pakistan, which was created in the name of Islam, will continue to survive only if it sticks to Islam. That is why I consider the introduction of [an] Islamic system as an essential prerequisite for the country’.

After his consultations with leaders of all political parties a few days after seizing power, Zia insisted that ‘all these political parties should work for establishing an Islamic order because this country had been created in the name of Islam and will survive only by holding fast to Islam’. A month later Zia professed that ‘the key to the welfare of the common man lies in the Islamic system which was promised to him thirty seven years ago’, a reference to the date when the demand for Pakistan was first voiced. ‘Had the Islamic system been introduced at the appropriate time,’ he claimed, ‘all the basic necessities of every citizen would have been met easily’…

…Zia’s Islamic rhetoric worried secular Pakistanis as well as non-Muslim minorities. If the chief martial law administrator planned on amending the Constitution to translate into reality his professed ideal of an Islamic state headed by an ‘amir’ and run under sharia, would he also limit the minorities’ rights to those of dhimmis in early Islam? A delegation of the National Council of Churches of Pakistan approached Zia about the ‘status of minorities in a truly Islamic state’ only to be assured that ‘their rights as a minority community would be fully protected’. Zia said that Islam laid down certain safeguards for rights of minorities in an Islamic state and added that these safeguards would be fully honoured.

Thus, within months of his military coup Zia was methodically building, on religious grounds, a structure of support to enable his indefinite rule. Zia lacked a legal or constitutional mandate and planned to exercise power with an iron hand. Two American academics observed at the time that Zia had introduced Islamic themes in all contexts. ‘There is talk of an Islamic cargo fleet, an Islamic science foundation and an Islamic newsprint industry and the All Pakistan Lawn Tennis Association has instituted the Millat Cup, ‘the first big tennis gala of Muslim youth’, noted the professors…

…General Zia-ul-Haq’s Western allies [also] did not notice the momentous changes he introduced in school and college curricula that fostered Islamist prejudices in young Pakistani minds. This was Zia’s quest to indoctrinate the country’s youth in Islamist ideology; it would have far-reaching adverse consequences for Pakistan’s religious minorities. And it would thwart the efforts of those who would cultivate a tolerant, more liberal ethos within the country. Zia’s quest began with a 1981 University Grants Commission (UGC) directive to prospective textbook authors. The directive told textbook authors to demonstrate through their writings ‘that the basis of Pakistan is not to be founded in racial, linguistic, or geographical factors but rather in the shared experience of a common religion’.

The stated purpose of the curricula changes was ‘to get students to know and appreciate the Ideology of Pakistan, and to popularize it with slogans’. The new textbooks were meant ‘to guide students towards the ultimate goal of Pakistan—the creation of a completely Islamicized state’. But their real impact was to falsify history, glorify jihad and warfare, denigrate religious minorities and instil religious prejudice into children’s minds in a systematic manner. Years later, experts find Pakistani textbooks educating children ‘into ways of thinking that makes them susceptible to a violent and exclusionary worldview open to sectarianism and religious intolerance’…

…Under the new education policy, the subject of Islamiat was made compulsory for all levels from primary school to college undergraduates. Teaching of Arabic, a language hardly spoken in Pakistan, was made compulsory in all schools to students belonging to all religions on the grounds that it would help in understanding the Quran. Schools now emphasized the ideology of Pakistan and teachers and professors deemed opposed to the ideology were weeded out. The Zia regime also encouraged madrasa education, declaring madrasa certificates equivalent to normal university degrees. This endorsement ignored that the pedagogy in these traditional religious schools was seriously flawed by contemporary standards, on account of its emphasis on learning by rote.

According to physicist A.H. Nayyar, the redesigned curricula created a monolithic image of Pakistan as an Islamic state and taught students to view only Muslims as Pakistani citizens. Muslim majoritarianism in Pakistan, in Nayyar’s view, amounted to creating an environment for non-Muslims in which they became second-class citizens with lesser rights and privileges; their patriotism became suspect, and their contribution to the society was ignored. ‘The result is that they can easily cease to have any stake in the society,’ he concluded…

…One of the many unfortunate consequences of Islamization of the educational system was the attacks by Islamists on free-thinking scientists and academics on campuses. When Pakistan’s only Nobel laureate, the physicist Dr Abdus Salam – an Ahmadi — visited the country, his lecture at the Quaid-i-Azam University in Islamabad was picketed by Islamic fundamentalists. As the New York Times reported, the protestors’ objections were ‘not directed at Dr Salem’s research but at the religious beliefs of the small community into which he was born’. In other cases, fundamentalist students attacked professors teaching evolution or social science theories considered blasphemous by Islamist clerics.

Some professors, such as Sultan Bashiruddin Mahmood, tried to teach what they called ‘Islamic science’, a concept openly embraced by Zia. Mahmood was a nuclear engineer who proposed nurturing the power of jinn (genies) mentioned in the Quran to solve the world’s energy shortage. ‘Mahmood was fascinated by the links between science and the Koran,’ reported the New York Times. ‘He wrote a peculiar treatise arguing that when morals degrade, disaster cannot be far behind’ and was fascinated by ‘the role sunspots played in triggering the French and Russian Revolutions, World War II and assorted anticolonial uprisings’. Thus, while students were being indoctrinated with the Islamist ideology of Pakistan, the country’s scientific community was also being undermined by pseudo-science. The stage had been set for conflict between Pakistanis’ aspiration for modernity and the idea of a puritanical Islamic state advocated by the clerics and their supporters.

This conflict may be largely ascribed to the perennial dissatisfaction of the Islamic extremists, whose worldview was, in many ways, anchored in the seventh century. No amount of reverting to mediaeval practices or promoting their cause, though, seemed to sate their religious fervour. Neither were they assuaged by the dwindling of the religious minorities in the country. By the time of the 1981 Census, Pakistan’s population was 96.67 per cent Muslim. Christians constituted 1.56 per cent of the population; Hindus amounted to 1.51 per cent, and Ahmadis numbered only 104,245 – or a mere 0.12 per cent of the population.

(Excerpted with permission from Purifying the Land of the Pure: Pakistan’s Religious Minorities by Farahnaz Ispahani, Harper Collins India, 2015)