Jambudwipa: The Seeds Of Political Unity In The Indian Subcontinent

The Mauryans are inextricably linked with the real idea of India through the ages.

The concept of the Mauryan Jambudwipa could well be thought of as the ancestor of India or Bharat of today.

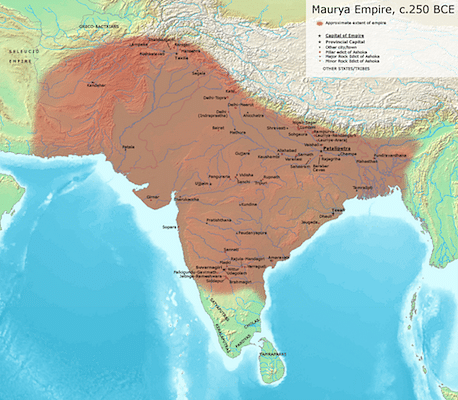

The peacock flag of the Mauryans was the first to unify the Indian subcontinent under one political rule. From the Kubha River of modern Kabul in the north to the Vaigai River of Madurai in the south, Saurashtra on the coast of the Sindhu Sagar in the west and the Gangasagar Sangam of the Bay of Bengal in the east – the dwipa-chakravartin ruled them all 2,300 years ago.

The name Jambudwipa comes from the sapta-dwipa vasumati formulation of antiquity and was consciously used by the Mauryans to refer to the kingdom.

From the emerging contours of the civilisation on the banks of the Sindhu and the Saraswati dating to nine thousand years ago, the scattered settlements of the intermediate periods, the emergence of the Vedic Age, the efflorescence of the sixteen janapadas that led to the primacy of Magadha and then that of the Nandas and the Mauryas, it was a long journey for the subcontinent.

The brain behind the political unification was that of Chanakya, whose legacy is with us in the form of the Sanskrit-language treatise, Arthashastra; the sword was that of Chandragupta, the son of a goatherd, a boy picked out for his destiny; and that of Jambudwipa, by Chanakya, according to legend.

Although stories about the origins of Chandragupta and Chanakya are many, what is not in dispute is their partnership and the taking over of the Nanda kingdom, only to expand it into one of the biggest empires of the ancient world. They were friends of the Seleucids in West Asia, and Suvarnadipa and Yavadipa, Thaton, Chu, Quin and Zhao to the east. Mauryan trade spread its roots across the world and was one of the foundations of the kingdom’s prosperity.

On the eve of the establishment of the Mauryan Empire, the Nandas had built on the accomplishments of the Haryankas and the Shishunagas and established a prosperous and well-run kingdom. They had maintained a massive army, which finds mention in Greek accounts of Alexander of Macedon’s foray into India and was the reason why his men, tired from a long campaign through Asia, refused to go any further into the subcontinent to try conclusions with its biggest kingdom.

Some accounts of Chandragupta’s early days describe him as honing his skills with fights against the Macedonian army, the guerrilla attacks masterminded by Chanakya. He is said to have collected his first army from the area around Swat, or Udyana, as it was known then.

Alexander’s short-lived streak through the kingdoms of the northwest made it easier for Chandragupta to defeat them. He took over Pataliputra, perhaps around 323 BCE, through a coup planned and executed by Chanakya, and then spent the first few years of his reign conquering or otherwise subjugating the kingdoms of what are now India and Pakistan, throwing out the nominal Greek presence in Punjab and co-opting the other existing kingdoms into his empire.

Then came a critical test, around 305 BCE – the growing ambition of Seleucus, one of the Diadochi of Alexander who had won the war of succession after the death of the latter and wanted to re-conquer the erstwhile Greek satrapies. Chandragupta had reclaimed the Indian territories of Alexander when the latter had returned after his men refused to fight the Nanda Army.

Alexander suffered from the unfortunate delusion that the Sindhu River would meet up with the Nile, and he would then be able to travel to Europe from northern Africa. He sent a fleet under Nearchus up the Indus, and himself started back via land. His army was caught in the Makran desert, and a good part of it died on the way back. He was poisoned, probably by a jealous lover, or died of a fever. So much for the world conqueror in India.

His successor, Seleucus, bolstered by his victories in Asia, was looking to control the Uttarapath, or the Haimavata Marg, as it is called in the Arthashastra, the main trade route in the north of India, which was the land route for traders to central Asia, Western Asia and, thence, to Arabia and further away, to Europe.

Chandragupta could not afford to let him do so. The prosperity of the Mauryans depended on trade. The creation of an agricultural surplus and the army, which maintained the safety and order for trade, commerce and agriculture to prosper, were the other aspects of its strength and riches.

Intricate details of the clash between Seleucus and Alexander are few, but Greek authors indicate that the two armies met on the banks of the Sindhu River somewhere near Takshashila. When the dust cleared, Chandragupta was master of the erstwhile Seleucid territories of Kabul, Herat, Kandahar and coastal Baluchistan. In turn, he gifted Seleucus with 500 war elephants, which Seleucus used to defeat his rival Antigonus in the decisive Battle of Ipsus.

According to some accounts, Chandragupta also married the daughter of Seleucus by his Persian wife, Apama. Thus began the era of Mauryan-Seleucid friendship. Megasthenes was the ambassador sent by Seleucus to the Mauryan court; he wrote his famous ‘Indika’ based on his sojourn in the subcontinent.

Chandragupta was succeeded by his son Bindusara, and then by his grandson Ashoka. After Ashoka, the successors were weak and incapable, and the empire was finally overthrown by its Senapati, Pushyamitra Sunga, in 185 BCE.

The Mauryan empire extended into central Asia in the north. In the south, Mauryan remains have been found up to Madurai, and there is mention of the Cholas, Cheras, Pandas and Satiyaputas, friends of the Mauryans, in Ashokan inscriptions. That the Mauryans exercised ‘friendly’ intervention and interference into the affairs of these kingdoms is attested to by some poets of the Sangam period, such as Mamulanar, Attiraiyanar and Parangorarnar. According to Buddhist sources, the Sri Lankan kings paid tribute to the Mauryans too.

The Indian Ocean littoral was well-connected with ports. The coastal sea routes went from Tamralipti on the eastern coast down through Veerampattinam and Tambapanni, included Jambukola of northern Sri Lanka and went up again to Muracipattinam, Surparaka and Bharukaccha. From there they crossed the Sindhu Sagar to Asia, Nabatea and beyond. These sea-ports were in turn connected through land to the Uttarapath, the great trade route of the north, and the Dakshinapath, the great trade route of the south. Four regional capitals were established at Takshashila, Ujjaini, Suvamnagari and Tosali.

There was a vast administrative and military system to keep all this in place. We have details of this not only from the Arthashastra but also the Indika of Megasthenes. The original text has been lost, but numerous references by others such as Strabo and Arrian give us an idea of Chandragupta’s Jambudwipa. This information is supplemented by numismatic, epigraphic, archaeological and literary evidence.

The kingdom was a monarchy, of course, with a king at its head. But there were also ministers, or mantris, to advise the king, and a parishad made up of these ministers, which exercised a powerful advisory function. The senapati, purohit, prime minister, queen-mother, queen and yuvraaj were generally the closest advisors of the king.

There was a complex system in place for the regulation of economic activity. According to the Arthashastra, and corroborated in some measure by Greek sources, there were around 34 different departments of the State to look after different areas. The State levied taxes to support the massive State apparatus.

There was also a complex and huge spy system to keep an eye on everything and act as the eyes, ears and public relations department of the king and the administration.

Some 2300 years ago, the Mauryans ran a multi-ethnic, multi-religious and multi-lingual country, stretching from Afghanistan to Madurai (the rest of the South also being in their sphere of control up to Sri Lanka) and Saurashtra to Bangladesh. The kingdom was a teeming mixture of different ethnicities and languages, Sanatan Dharma, Jainism, the cults of Buddha and Makkali Gosala – all vied for the patronage of the people and the kings. There was also a sizeable foreign population and a special department to look after them.

Directions were given by the Samrat, with the advice and support of his parishad, and disseminated across the empire in all the different languages in use in the empire, ranging from Maagadhi to Greek to Aramaic to Tamizh. There was an entire department for the copying, transcribing, translation and dissemination of royal commands, edicts, instructions and so on to run this vast and complicated kingdom. Ashoka’s major and minor edicts, as well as pillar inscriptions, are a testimony to this. Maagadhi was used for Pataliputra and around, but was translated into the different languages spoken through the length and breadth of the empire.

How did they manage the conflicts inherent in this complex society when interests clashed between villages, districts, cities, guilds or religious organisations? What were the principles guiding the resolution of these matters by the king and at many other different levels? Was there any concept of ‘nation’ as we understand it today? Was it a country as India is now?

It will be instructive to compare the Mauryans to the Westphalian model of a nation-state since that is the one, which, after centuries of eurocentrism, is often posited as the only model of a nation-state.

The loyalty to a greater concept, in the Westphalian case an abstract State which is all powerful, was mitigated by concentric circles of loyalty in the case of the subcontinent. The humble citizen first owed loyalty to his village and his local gods before going on to further, larger units of administration, and then ultimately the king. The point to note is that the king was not an ever-present figure in the daily life of the village. Local institutions took care of things, and it was only the most serious issues which needed to go up to the king.

There were different codes of law which were followed in different parts of the kingdom, but the king’s decision was final.

To take the example of guilds, which ran the economic activities of the kingdom, there were 18 major ones, including carpenters, goldsmiths, weavers and so on that were registered with the king. They had specific and exclusive rules and codes applicable to their members and their internal forums for resolution of issues. It was only in cases of conflict between them that the issue would go up to the king for adjudication. They were the ‘corporate entities’ of those days.

Also, there were different local models of political administration. The Mauryan kingdom subsumed tribal oligarchies, for example, whose functioning was allowed by the imperial power. These would not be allowed to exist or recognised in the Westphalian model of sovereignty.

Another very important difference is in the conceptualisation of the role of religion. The Westphalian model insisted on the division of the church and state since the Treaty of Westphalia had also aimed to limit the power of the Catholic Church. Temporal and spiritual power walked, more or less, hand in hand in India, and religion was a moral and ethical force, with the raj-purohit providing moral direction, and the king himself being in service of the gods.

It would be pertinent to remember that this was not a monolithic, congregational, messiah-based religion but a polyglot of many local practices, where the ‘little’ traditions oiled the wheels of the ‘great tradition’ (after Redfield and also MN Srinivas’s Indian exposition). This was the over-arching structure, and kept the edifice intact and functional. This, to my mind, is the uniqueness of the Indian model; all differences are allowed to exist and become a harmonious part of an inclusive whole.

The ‘State’ in Mauryan times did the same things that states today do. There was a common defence system, a huge standing army, a common currency, centrally formulated foreign policy and a bureaucracy which oversaw the functioning of the country.

What was not there, and is still not there, is the prevalence of one language, one culture or one race of people. The State knew its territorial extent and guarded it very well but without imposing more than necessary uniformity. The principles which were to operate in the entire kingdom were enforced, but a strong ‘Centre’ let the ‘States’ operate with comparative freedom, although sources of revenue for the Centre were very strictly protected.

It is an interesting point that, territorially speaking, neither the golden age of the Guptas nor the Mughals, the British or the current state of India have administered such a large area ever again. For good reason is the Mauryan Empire called the ‘First Empire’.

It is worth noting that two of the imperial Guptas, including arguably the most famous of them, Chandragupta Vikramaditya, also called themselves ‘Chandragupta’. Firoz Shah was motivated to drag two Ashokan Pillars to his capital city and establish them there. The modern Indian State, too, borrowed the Mauryan symbol of the Lion Capital as its own.

The Mauryans are inextricably linked with the real idea of India through the ages and the concept of the Mauryan Jambudwipa could well be construed as the ancestor of India or Bharat of today.

Also Read :