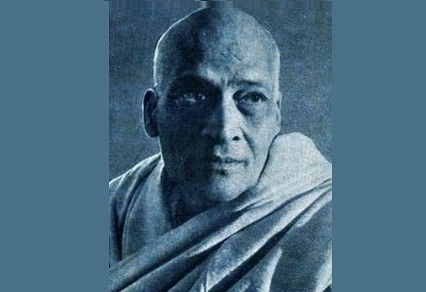

Khasa Subba Rao

A brief profile of Swarajya’s founding editor.

Remembered today only by a few, Khasa Subba Rau was an inspiring figure from his era, a time already known for several such men and women. Although he played a small part in the freedom struggle too, Khasa earned his reputation for his bold journalism, ethical clarity, intellectual honesty, and the rare ability to speak truth to power.

Born in January 1896 into a Yajnavalkya Brahmin household in Nellore, Andhra Pradesh, Khasa graduated from Presidency College, Madras, with a degree in Philosophy. To this, he added certificates in law and teaching. It was at this time that Khasa was inspired by Mohandas Gandhi’s example and joined the Non-Cooperation Movement in 1921. One of the great influences in Khasa’s life was Tanguturi Prakasam, the future chief minister of Andhra Pradesh. Khasa joined Prakasam’s English daily, Swarajya, in 1924 and stayed with it until its closure twelve years later.

In 1930, Khasa took part in the salt satyagraha, and soon after, in 1932, he was severely beaten by the British while picketing a foreign clothes shop. Between 1936 and 1946, Khasa worked in several newspapers including the Indian Express but in February 1946, he started his own weekly magazine, Swatantra. The journal lasted for ten years during which it made a name for itself as a loud champion of public causes.

When Swatantra had to shut down due to financial difficulties, Khasa started Swarajya in July 1956 with C Rajagopalachari’s blessings. He ran the weekly for three years, when owing to his age, he handed over the management to T Sadasivam and continued as life editor. Khasa enjoyed writing his column, Sidelights, and continued to do so until his last day: he passed away on June 16, 1961 and his final column appeared on June 17, 1961.

Throughout his career, Khasa had a few clear principles. One was to never severely criticise someone he disliked or excessively praise anyone he liked; he feared that extraneous emotions may cloud his critical faculties. Another was to speak the truth as he saw it then, and politely. During his days at Swatantra, he had a sharp falling out with Rajagopalachari over the latter’s role in the dismissal of T Prakasam as chief minister of Madras State. When Rajaji asked to cancel his free copy of Swatantra, Khasa did so and wrote back in a letter quoting Rajaji himself, “to refrain from honest criticism…is a disservice to the cause. A fearless critic is a friend. A journal that prefers to flatter or be silent for safety’s sake is by no means a friend.”

Khasa was quite firm about editorial independence. Once, when he was working at the Indian Express, Khasa clashed with the press baron Ramnath Goenka over the former’s column. Khasa made it clear in no uncertain terms that editorial importance was of utmost importance in a newspaper. “If you are competent to supervise my work, you are competent to be the editor as well,” he told Goenka. Another incident occurred when Goenka tried to bring out a special edition of the Indian Express to celebrate the Maharaja of Travancore’s birthday. Khasa threatened to resign rather than lower his newspaper to print “advertisement puff.”

Not even the Prime Minister of India was spared Khasa’s scrutiny. Jawaharlal Nehru and his party, the Congress, were regularly and thoroughly lambasted over corruption, nepotism, socialism, foreign policy, and authoritarianism in his column. A simple man charmed by Gandhian ideals, Khasa was aghast at how the Congress had “replaced rules with nepotism” and used its power for the benefit of all but “for the advancement of its own adherents.” He did not hesitate to accuse the Congress of selfishness and communalism nor its leader authoritarian.

When legal action was threatened against him by the Speaker of the Lok Sabha, Khasa replied in his usual sharp manner, “The threatened action is awaited.” No action was taken.

Despite being an ardent supporter of the Congress during the days of Gandhi, Khasa felt betrayed by the party’s Nehruvian ideology. As a result, he gravitated towards Rajaji’s Swatantra, advocating a balance of free market and welfare.

Despite accusations of editorial partiality, Khasa remained firmly committed to the highest ideals of journalism. “The appeal of the Press should be always to the vast body of uncommitted readers,” he said, “and not to sectional coteries already converted to some rigid doctrine. To let down the uncommitted by propagating fixed partisan nostrums is to offend truth itself.” Not only was he not afraid to speak his mind but he was not afraid to change it when convinced of the error of his ways.

Throughout his life, Khasa embraced a Gandhian simplicity and remained a humble man despite his friends in high places. His unimpeachable ethics and keen mind marked an era of Indian journalism that has been seldom seen since.