Konark Is Dying; For The Sake Of Future Generations, We Must Intervene

The thirteenth-century monument is one of India’s greatest marvels but has suffered periodic neglect.

The ASI appears to have washed its hands off its preservation.

Konark, a world-class monument and Odisha’s invaluable heritage, is dying, slowly.

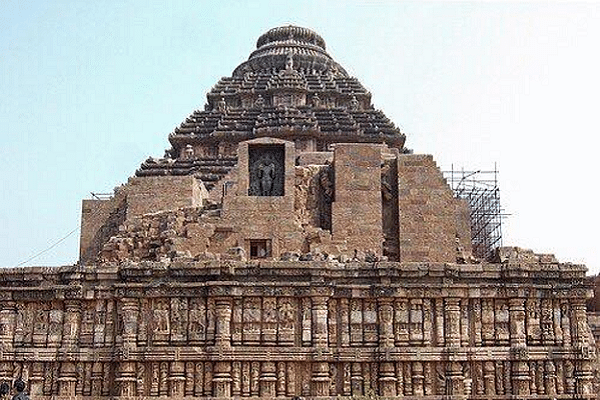

The main tower of the complex collapsed some hundred years ago, but the remains still attract lovers of art and culture. Built by King Langula Narasingh Deba of the Ganga dynasty in the thirteenth century, this architectural marvel was in a dilapidated state for nearly a century.

Its restoration and conservation began from the late nineteenth century and the process is still under way. In 1979, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) turned concerned about the conservation efforts, and in 1984 enlisted the monument as a ‘World Heritage Site’.

The Sun Temple is protected under the National Framework of India by the Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Sites and Remains (AMASR) Act, 1958. Other legislations include the Forest Act, Konark Development Act and the Notified Council Area Act.

Under the AMASR Act, a zone of 100 metres outside the property and a further zone of 200 metres outside it constitute, respectively, ‘prohibited’ and ‘regulated’ zones for development or other similar activity that may have adverse effects on the outstanding universal value (OUV) of the property. All conservation programmes are undertaken by the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI).

From 1806 onwards, many measures had been taken up by the then British government in collaboration with local kings and the ASI.

In 1867, the Asiatic Society of Bengal attempted to relocate an architrave of the Konark temple depicting the Navagraha, to the Indian Museum in Kolkata. This attempt was abandoned due to non-availability of funds. In 1894, 13 sculptures were moved to the Indian Museum. After this, the local population objected and work was stopped.

In 1903, when a major excavation was attempted nearby, the then lieutenant governor of Bengal, J A Baurdilon, ordered the temple to be sealed and filled with sand to prevent the collapse of the Jagamohana. The Mukhasala and Nata Mandir were repaired by 1905.

After Independence, several experts were deputed from the ASI, government of India and UNESCO to suggest preservation methods. Out of the many recommendations, some were executed and others merely remained part of the discussion in closed rooms.

In 1998, a heavy stone slipped from the northeast corner of the Mukhasala. While the media highlighted the issue, no inquiry was commissioned.

In 2006, a consulting firm, SIMTEK, visited Konark and found that the sand stored inside had collapsed 16 feet below. They immediately recommended removal of the sand from inside the structure. But this recommendation fell on deaf ears.

In 2009, Dr Satya Murty of the eastern circle of the ASI convened a meeting in which eminent historian Dr Rajendra Prasad Das insisted on the same measure. He also recommended that the sand be removed and conservation work on the interiors of the structure immediately commenced. But even his advice was ignored.

On 5 December 2009, a meeting, attended by many distinguished scholars, was held. The Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage (INTACH) lamented that in the name of preservation, many plain stones were being used to replace the sculptured stones of the temple. This is an issue most visible in the temple at present, with plain stones replacing panel after panel, jarring the beauty and grandeur of the temple. It has been 10 years since the issue was identified, but there has been no acknowledgement of the concern as yet.

A visit to the temple would make it impossible to ignore the ubiquitous signs of decay. The structure is crumbling and conservation efforts leave much to be desired. Some of the critical problems that cannot be missed now are:

- Several stones which had fallen from the top of the structure since years are yet to be restored to their original position.

- During the monsoons, water clogging inside the complex is a major problem. Visitors have to wade through knee-deep water. This concern was raised several times by the state government as well as by concerned citizens on social media and through public interest litigation (PIL) petitions.

- Various sculptured stones are being replaced by plain stones and the temple is slowly losing its charm, beauty and grandeur.

- The Jagamohana is at risk due to lateral thrusts on its structural walls. The conservation of the remaining part of the temple will be a challenge after removal of the sand.

So how can this issue be addressed to ensure Konark does not keep sliding towards destruction?

- Technology must be used for structural surveillance like station videography, thermal imaging et cetera.

- There is a need to thoroughly study the impact of the stream from the Chandrabhaga river, on the structural integrity of the temple. This may reveal why the temple collapsed and will also provide indications on how the remaining structure could be protected from impending damage.

- The lost architecture should be restored to its earlier glory by engaging skilled stone craftsmen. This would be a better alternative, rather than replacing everything with plain stone.

- Proper cleaning and surface repair of the standing structure needs to be carried out.

- Drainage systems must be cleared and regularly maintained to avoid water clogging during the rains.

- Damage to the structure is not just man-made as it has seen centuries of wear and tear owing to environmental factors. But now that we can possibly address some of the concerns, there is a need to begin with a thorough study of the various environmental factors at play in the area and how they interact with the integrity of the structure.

The degradation of the monument is the result of interaction between material and environmental factors like heat, moisture, atmospheric pollutants, water and living organisms. The interaction starts at the surface and then progresses inwards. It may reach several millimetres or even centimetres and may lead to significant loss of strength of the stones, resulting in erosion and degradation.

It is now almost clear that the ASI is not interested in the work at hand in Konark. Only when the restoration work is completed and conservation efforts are diligently attended to, can all four doors to the temple be opened and the monument be brought back to its former glory. With such a critical part of the structure being shut off, thousands of people are missing out on the monument, in all its grandeur. It is unfair to the temple and its legacy that visitors be kept away and not allowed to see its Ratna Singhasana and Parshwadevatas.

It is high time for all heritage lovers to come forward and make an appeal to the government to hand over the restoration work to an organisation such as UNESCO. It should be clearly mandated that visitors be allowed into the monument through all four doors and its lost architecture restored to its full glory. The UNESCO has undertaken critical conservation work at various important cultural sites around the world and it could bring the same expertise and experience to Konark as well.

There is a strong possibility that Konark, as we have known it, might perish if there is no timely intervention.

The most important thing at this point is to have an organised world-voice, which can force the authorities to undertake the necessary preservation, conservation and restoration work of this monument. And it must be done urgently, so that Nobel laureate Rabindranath Tagore’s words on Konark continue to ring true when future generations behold this marvel:

“Here the language of stone surpasses the language of humans”

Please save Konark.