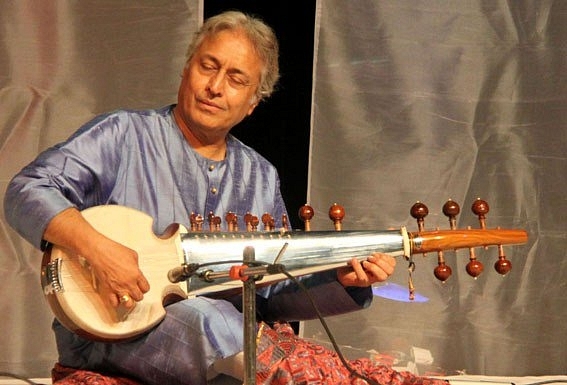

Melodious Musings: Sarod Maestro Amjad Ali Khan On Musical Legends Of The Twentieth Century

“Various permutations and combinations give the scales the shape of a raga. However, a raga is much more and beyond. It’s not just a mere scale. A raga has to be invoked, understood and cared for, like a living entity”muses maestro Ustad Amjad Ali Khan’s in the introduction in his book Master on Masters, a deeply personal account of the lives of 12 musical legends.

True to the spirit of a country where music is seen as not just art or entertainment but divinity incarnate, the number of musical legends and their contribution to the universe of sounds is unparalleled. And when a legend narrates the tales of the lives and times of some of the greatest icons of Indian classical music through, they come alive and how.

Sarod maestro Ustad Amjad Ali Khan’s Master on Masters, is an anecdotal account of his knowing and interaction with twelve musical legends of the twentieth century which includes the likes of Bade Ghulam Ali Khan, Amir Khan, Begum Akhtar, Alla Rakha, Kesarbai Kerkar, Kumar Gandharva, M.S. Subbulakshmi, Bhimsen Joshi, Bismillah Khan, Ravi Shankar, Vilayat Khan and Kishan Maharaj.

Here is an excerpt from the book that gives a glimpse into the life of Kumar Gandharva:

The essence of Kumar Gandharva’s musical career lies in his effort at experimentation. The early part of his career was spent in researching the folk music of Malwa and the region around Dewas, Madhya Pradesh, which he made his home. This intense study resulted in new ragas based on folk tunes, an innovation in the field of music.

I personally admired Kumarji’s vision and musical canvas which was full of colour. He had a vast repertoire of music consisting of khayal, thumri, tappa, tarana, bhajan, etc. He was a temperamental artist, which is quite understandable.

In the early years of his life he was stricken with tuberculosis. Although doctors told him that he would never sing again, in time, with the emergence of streptomycin as a treatment for tuberculosis, he recovered and began to sing again. However, as one of his lungs had collapsed completely due to his illness, he came to be known as the miracle man who sang and survived with only one lung.

Kumarji and I kept meeting at music festivals through the 1970s and ’80s. Sometimes he sang after my sarod recital and sometimes I concluded the festival after his performance. Between 1973 and 1979, Kumarji sang almost every year in our music festivals in memory of my guru and father, Ustad Haafiz Ali Khan Sahab. In the early 1980s, Kumarji invited me to Dewas for a festival he used to organise. After the concert, he invited me to his residence for dinner where I met his elder son, Mukul Shivputra, who today is a genius vocalist. My wife Subhalakshmi and I have been very fond of Mukul since his youth. I am happy and proud to see Mukul’s following and admirers all over India.

I am sure the message and the legacy of Kumarji will be carried forward by all his followers and disciples, especially Mukul and his son Bhuvanesh. I understand that Mukul’s younger brother Yashovardhan lives in Canada. Though I never got the chance to meet him, I believe that he is a good film-maker and an artist.

Kumarji’s second wife Vasundhara Komkali was an established singer, as is their daughter, Kalapini Komkali. Kumarji had many recordings but I found one particularly moving and appealing. It was of Nirgun bhajans by Vasundharaji and Kumarji. The beauty of the album lay in the fact that though there were two voices, it sounded like one voice. It is indeed rare to find a gifted and accomplished musician so engrossed in experimentation with and a deep exploration of the innumerable aspects of music, and rarer still to find a thinker-performer capable of giving verbal and musical expression to his thought.

Once, I was driving down from Indore to Bhopal with my mother and my wife, Subhalakshmi. While passing through Dewas, I suddenly realised that this was Kumarji’s home. On a whim, we decided to visit him. That was the first time I met Vasundharaji. She ran inside upon seeing us and reappeared, her head properly covered, with Kumarji who was very happy to see all of us. There was a beautiful gazebo-like structure in the garden with a swing that captured India’s old-world charm. Kumarji sat on the swing, and we spoke for a long time.

Vasundharaji gave us tea and delicacies. We really enjoyed their warm hospitality. I must mention Sriman Vasant Achrekarji, Kumarji’s friend, manager and also tabla accompanist. Achrekarji was Vasant Desai’s assistant in the 1950s but later devoted himself fully to his role as an accompanist to classical singing until his death in the late 1970s. Kumarji also received immense support and admiration from Pandit Vinay Chandra Maudgalya and the Gandharva Mahavidyalaya of Delhi.

Kumarji’s teaching gave us a deep understanding of how every raga is full of infinite possibilities, despite the seemingly constraining rules of classical music. He never fostered the culture of giving a rote performance or copying the readymade alaaps of one’s teacher.

His striking new creations included morning ragas like Saheli-Todi, Beehad-Bhairava and Bhavmat-Bhairava; the afternoon raga, Madhsurja; the evening raga, Sanjari; and the night ragas, Malavati, Lagan-Gandhara, Rahi, Ahi Mohini and Maghwa. Another well-known creation is the Raga Gandhi-Malhara. Then there are his compositions for the season: Geet Vasant, Geet Varsh and Geet Hemanta.

Through my conversation with his student Madhup Mudgal, I learnt that Kumarji taught every raga elaborately through its notes, the bandish came much later. Every lesson with him was like a concert, as he taught the nuances with enjoyment, and a fair amount of admonition thrown in. The progression of alaaps through the varying tempos was done in detail. He always took care to teach the traditional and basic ragas such as Bhairav, Todi, Bhimpalasi, Bilawal, Kalyan and Bhoop, etc., before proceeding to the uncommon or his self-created ragas. His lessons included expositions on the bandishes of various gharanas, the unique features and vocal styles of their leading singers and listening to various recordings with him.

It was a complete learning experience, where music enveloped the student totally; from the music room to the dining table to the veranda outside, at all times of the day. Kumarji taught only those who deeply revered music. Many a great name was denied his tutelage when he sensed a glib smartness instead of dedication. But for those who worshipped music, Kumarji made time unconditionally.

Kumarji made the complicated task of transcending from the grammar of music to its artistic beauty very simple. It is hard to explain why Kumarji’s rendition of a raga stood out so brilliantly among performances by other musicians of the same raga, and gave much more enjoyment. The flawlessly tuned tanpuras, the absolute purity of swaras, the raga progression that was so faithful to its spirit, the effortless yet complex manipulations of tempo and beats in the singing and, of course, the exquisitely conceived taans that evoked the raga in its depth and which were not mere vocal exercises—all these factors contributed to his magical uniqueness.

From Kumarji one learnt to be more than a musician. He cultivated an appreciation of the entire spectrum of the fine arts. His was a mind open to all aesthetic beauty and human perfection, be it nature or the seasons, sports or culinary arts. His friends included authors, sculptors and architects, as well as people from other walks of life.

Kumarji has often been criticised for breaking from tradition. In my opinion there has not been a musician with greater regard for tradition than Kumarji. A traditionalist is not one who simply carries forward the content received from one’s guru, unchanged. Kumarji rightly believed that tradition is the ever-flowing river into which you never step twice. That which ceases to flow is nothing more than a stagnant puddle.

Excerpted from Master on Masters by Amjad Ali Khan, Penguin Random House India , 2017 with the permission of the publisher.