Satire in Hindi Cinema: The Limits of Being Off Limits

Most mainstream films confuse satire with a license to get away with anything.

The purpose of satire is to strip away any semblance of half-truths and be scathing enough to shatter comforting illusions.

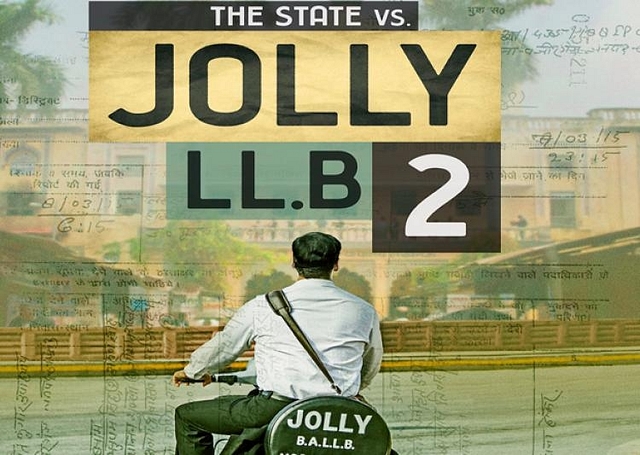

Following the petition of a lawyer, the Bombay High Court formed a three-member committee to review Jolly LLB 2 (Subhash Kapoor, 2017), a film about a lawyer who takes on the might of the Indian judiciary to correct some wrongs done by him.

The sequel, or to use the correct nomenclature, the ‘reboot’ of Kapoor’s previous film Jolly LLB (2013), also appeared to be one that starts off by being a satire and meanders into the realm of a social drama. The David–like–hero (Akshay Kumar in 2017 and Arshad Warsi in the 2013 version) takes on the all-encompassing Goliaths, ‘the system’ that at times lets the guilty get away. The court–formed–committee found four scenes to be objectionable and ordered their removal.

While two scenes included objectionable signalling and dialogues during an argument in the court, one showed a shoe being hurled at a member of the judiciary and one showed a judge, played by Saurabh Shukla, hiding behind his chair. Social media was rife with the paradox of the judiciary clamping down on a film that shows a lawyer taking on the judiciary and that the producers of the film in effect agreed by not challenging the judgment in a higher forum. Without getting into the merits of the said judgment that has left many divided in opinion, it can be safe to say that satire is a tricky business especially when the subject in question is the sole authority to decide its extent.

The champions of free speech could argue that there shouldn’t be any debate about satire, for either you get it, or you don’t. The purpose of satire is to strip away any semblance of half-truths and be scathing enough to shatter comforting illusions.

That is why, a film such as 3 Idiots (Rajkumar Hirani, 2009) immediately endears itself across a wide array of audience. Also, good satire can have the biggest impact in the shortest time. Take for instance, the Tamil remake of Munna Bhai M.B.B.S. (Rajkumar Hirani, 2003) whose title Vasool Raja, M.B.B.S. (Saran, 2004) was enough to enrage the medical community in Tamil Nadu. The state’s medical council filed a petition stating that the film’s title ‘vasool’ (denoting someone who collects protection money) tarnished the image of the medical fraternity. Of course, the reality of the medical profession becoming a money sucking exercise in some cases did not seem to convince the council members to ponder and look inwards.

But when it comes to popular Hindi films, satire as a tool becomes complicated because filmmakers at times end up treating it condescendingly. This is the inescapable feeling that refuses to leave viewers, post viewing most mainstream Hindi films that use satire. It is not that Bollywood does not understand satire as a tool, but it’s penchant to tie all loose ends, and the need to offer a solution undermines the power of satire.

In the recent past, Peepli [Live] (Anusha Rizvi, 2010) would be the ideal example of a film where satire was used to great effect. The film– a farmer Natha (Omkar Das Manikpuri) decides to commit suicide and the national media as well as political parties descend upon the village to witness the rare event with the former there to ensure it goes ahead as planned and the latter to make the most of the situation– rarely fools itself about the nature of the narrative. As a result, the viewer is not played around with, and the ending of the film - Natha runs away from it all, and we see him as one amongst the hundreds of faceless construction workers in a bustling metropolis – does not bother about the proverbial tidying up at the end.

In many ways, Peepli [Live] follows the more traditional format of satire where it compels you to look inward. It also seems closer to the social satire of the great Hindi writer Shrilal Shukla, best known for his iconic book Raag Darbari (1968). Shukla’s book is one of the greatest satires ever written, and he uses emblematic characters to put the spotlight on the political realities of India.

In a description of the world that Shukla’s Raag Darbari creates, Suresh S. rightly mentions that, like “each note in a raag having its fixed frequency, each character symbolises a certain political aspect.” Like any great satire, Raag Darbari also foresaw things that would become commonplace in the Indian political landscape. The book’s central character Vaidyaji heads a co-operative, whose manager robs it and runs away but Vaidyaji argues that as the government owns the co-operative it is the government’s duty to catch the culprit. He washes off any responsibility and later resigns on moral grounds but not before getting his son elected as the new head.

Think Fodder scam and Lalu Prasad Yadav. In spite of addressing some of the gravest ground realities destroying the social fabric of the country at the grassroots level, Raag Darbari still retained a spirit of fun. Shukla used new and even odd angles to put across truths of life, and you can see its influence on the films of the middle-cinema of Hrishikesh Mukherjee and Basu Chatterjee from the 1970s and the 1980s. It might not be totally incorrect to believe that Raag Darbari also influenced Kundan Shah’s Jaane Bhi Do Yaaron (1984) in a silent but obvious manner.

When compared to Peepli [Live] or Hrishikesh Mukherjee’s Naram Garm (1981) or Basu Chatterji’s TV series Rajni (1985) or Kirayadar (1986), the satire in contemporary popular Hindi cinema such as ones Rajkumar Hirani makes is structured and even western in its outlook. Often considered to be the present-day Hrishi da, Hirani’s narrative uses satire more as a tool to help reach a foregone conclusion. The lead characters, too, are laced with unbridled sympathy that creates a foundation to exonerate any of their flaws, which otherwise would augment the satirical elements, without much effort. In his breakthrough film Munna Bhai M.B.B.S., the protagonist is a petty goon who poses as a medical student to teach a doctor (Boman Irani) a lesson for insulting his father (Sunil Dutt), who believed his son was a doctor. The film had a strong resemblance to Patch Adams (Tom Shadyach, 1998), where a doctor (Robin Williams) uses his joie de vivre to treat patients more than science. So, isn’t the irony of satire lost when a goon posing to be a medical student gives professional doctors a mega-life lesson in the form of the film’s prominent line -You treat a disease, you win, you lose. You treat a person, I guarantee you, you'll win, no matter what the outcome. In the same way, the entire argument in 3 Idiots – Indian education system unjustly burdens the young minds by instilling a fear of competition and failure – becomes contradictory for that is the tool that inspires rigor in Rancho (Aamir Khan) to substantiate his uniqueness. Similarly, his P.K. (2014) takes a satirical look at organized religion but hovers around a singular point of idol worship being the greater evil.

Most mainstream films confuse satire with a license to get away with anything and yes, that is one of the tenets of effective satire but is satire better when it works on both sides? Neil Blomkamp, who made the riveting District 9 (2009) where a government agent (Sharlto Copley) becomes exposed to the biotechnology of an extraterrestrial race forced to live in slum-like conditions on Earth, says that satire allows to make fun of everything and also allows you to make fun of both sides.

When compared to P.K., Oh My God (Umesh Shukla, 2012) where an atheist Kanji (Paresh Rawal) decides to sue God for the insurance companies attribute his loss to an ‘act of god’, also looks at the business of idol worshiping and organized religion but the narrative has an added layer. Here, God (Akshay Kumar) reveals himself to Kanji and asks why should he be held responsible for the blind faith that mortals have in god men and women in his name when he hasn’t asked this of them?

Popular perception would have you convinced that satire must, in the least, mock their subjects. But truly effective satire, in the words of comic T.J. Miller, is one where you respect your target enough to understand every aspect of it, so you can more effectively make fun of it. This is what many contemporary Hindi filmmakers seem to sidestep, to get the maximum and easy laughs. So, in effect and hindsight, does this mean that the likes of Jolly L.L.B. did not really understand how things worked? Had the filmmakers simply read Shrilal Shukla they would have known that sometimes stating the truth as it was, is enough, to not only get the laughs but also make a statement as opposed to designing satire to be… well, satirical.