The Mindless Scissors

The people who play the most significant roles in the process of film certification in India are appointees of political whim with little qualification for the job.

Psychoanalyst Sudhir Kakar calls Indian popular cinema a “group day dream” or a “vehicle of shared fantasies of a vast number of people living on the Indian subcontinent who are both culturally and psychologically linked.” In a country, which produces more than 1000 films annually, cinema is both a mirror and an influence. For such an important medium of expression, we as a society have shown remarkable apathy to the system regulating it.

Following the arrest of some Censor Board officials on bribery charges, the Minister for Information and Broadcasting has promised to make the process of film certification simpler and transparent. Unfortunately, the roots of corruption and un-professionalism in Indian film certification traverse far deeper than the usual problems of opaqueness in process and functioning. What we really need is a complete overhaul of the law, as was suggested by an expert body headed by retired High Court Chief Justice G. D. Khosla, and endorsed, as it was, by the Supreme Court way back in 1971.

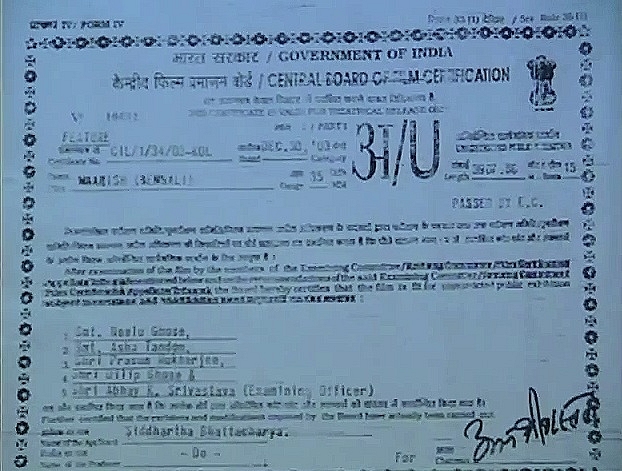

The most unique feature of censorship in India is that the actual examination and certification of films is carried out, not by the statutory Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC), but by Advisory Panels, whose members are appointed exclusively by the Executive. Though the Cinematograph Act of 1952 does not make the establishment of such panels mandatory, and requires these panels to only ‘enable’ the CBFC in discharging its functions, the rules, subsequently framed under the Act, have had the effect of expanding the role of these panels vastly.

It is no doubt true that it would be impossible for a centralised body of a handful of people like the CBFC to examine hundreds of films being released in different languages; the Advisory Panels have therefore become an indispensable part of the system. But, the law does not prescribe any qualifications for members of advisory panels (except a vague prescription that the members should be able “to judge the effect of the film on the Public), and as a result the persons appointed to these panels often tend to be highly unqualified for their jobs.

In allowing the Central Government to appoint “any person whom it thinks fit to be a member of the Advisory Panel,” and in granting such members the right to “hold office during the pleasure of the Central Government”, the law has created a distinct problem in regulating censorship in India. To make matters worse, because there is no limit on the number of members who can be appointed, in cities such as Hyderabad, Chennai, Mumbai and Delhi, there are presently, according to estimates, more than 200 to 300 panel members advising the CBFC.

The present head of the CBFC Ms. Leela Samson has candidly admitted that “the advisory panel has a wide representation of people from all walks of life. Some are doctors, lawyers, journalists, mothers or viewers with an informed opinion. Others are simply political workers recommended by party bosses who have little or no interest in cinema”. The problem is self evident: how are doctors, lawyers, and journalists competent to “judge the effect of the film on the Public”. What’s more, as Ms. Samson admits, many of these persons secure membership only through political patronage. Recent arrests by CBI reveal that bribes were routed to the CEO of the Censor Board only through advisory panel members who in turn dealt with filmmakers directly or through agents.

As a result, the people who play the most significant roles in the process of film certification in India are appointees of political whim with little qualification for the job. This system of appointing advisory panel members was, in fact, identified by the Khosla Committee as the “most important defect destroying the efficiency of the board.” These advisory panels therefore ought to be replaced by state-level certification boards of fixed number of members, whose constitution ought to be prescribed by the Cinematograph Act.

The existing law is silent on two key areas: the basis/ guidelines for certification and the qualifications for examiners. The majority of the current CBFC members are from the film fraternity. This would be fine if the job of the CBFC were to assess the quality of the films, to judge, say, their literary or artistic value. But the question begs to be asked: how are film actors and film critics competent to certify whether the content of a particular film is suitable for an audience of a particular age group? In fact, it might be further asked: is it possible for a few individuals, no matter what their expertise, to assess the suitability of a film for such a diverse audience in the light of rapidly changing social trends and preferences?

Section 5B of the Cinematograph Act enables the Central Government to frame guidelines “to grant certificates under” the Act. The guidelines that have been framed under this provision are too brief, vague and make no reference to the sole criterion for classification of films viz. age of the audience.The Khosla Committee found these guidelines “incapable of objective application”. This is in total contrast with the seriousness with which many developed countries deal with film certification.

In the UK the British Board of Film Classification (BBFC) conducts a nation-wide survey every four years to frame and revise guidelines. The survey is conducted by market research experts and covers sizeable samples of youth and parents with children of different age groups. Based on these surveys the BBFC has identified ten broad themes to assess the “psychological impact” of a film on its audience. The themes are: sex, drugs, language, violence, blood and gore, medical gore, horror, imitable behaviour, nudity and smoking and alcohol. Each theme is assessed based on factors, which are identified in the surveys as justifying or incriminating it.

For instance, reference to drug abuse is permitted even in a children’s movie if the message is educational, whereas it is discouraged in an adult movie if it tends to “normalise” such behaviour. Studies also highlight how even among minors the impact of these themes varies between age groups. In Britain, films are certified in seven categories. Audiences below 12, 15 and 18 years of age are treated as separate categories. For example, the BBFC survey for the year 2013 showed that majority of parents with children below 12 years of age strongly disapproved any reference to sex or sexual content in films watched by their kids whereas parents with 15 year olds did not mind mild sexual content especially if it was accompanied by comedy.

This shows how unscientific it is to treat all minors in one category for the purpose of film classification, as is done in India’s Cinematograph Act. In many other countries, including Australia and Canada, minor audiences are classified into at least two age groups.

Since film certification involves judging “the effect of the film on the Public,” there ought to be a carefully devised method through which as many stakeholders from the general public are allowed to participate. When the British first toyed with the idea of censorship in India back in 1927, the Committee concerned issued a questionnaire regarding the desirability of censorship to hundreds of individuals from all walks of life. Interestingly, when as a part of the survey, the nationalist leader Lala Lajpat Rai was asked about permitting “cabaret scenes” and “underworld scenes” in films, he replied saying, “I don’t want the youth of this Country to grow up in a nursery.”

The Goverment should first frame detailed and scientific guidelines for film certification with public participation. These guidelines should be reconsidered periodically to keep pace with changing public preferences. It should then lay down specific qualifications for CBFC members to ensure they are capable of applying these guidelines bearing in mind the “psychological impact” of film content on audiences.

Till then, innocuous phrases like “I am a virgin” will continue to be censored on grounds of obscenity, whereas item songs with lyrics objectifying women would be certified for universal viewing, even when experts have not discounted linkages between such content and juvenile crime.