This Art Space In Thanjavur Takes Us Back In Time – And Adds Depth And Colour To The Present

How artists have transformed a quiet space in Thanjavur into arty Indic paradise.

The Southern Zone Cultural Centre is situated in the Medical College Road of Thanjavur. It is an autonomous body under the Union Ministry of Tourism and Culture and covers the southern states of Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Kerala, and Tamil Nadu, and Puducherry, Andaman and Nicobar Islands, and Lakshadweep. The campus is seven-acre large and hosts different cultural programmes. It is filled with grass and terracotta images.

The centre also conducts workshops in different schools of painting from various states – mainly their folk traditions. The folk artists, painters of calendar art as well as students of painting have been asked to paint every panel of the campus wall.

The result is an astonishing art gallery of various folk and calendar art paintings from across India. Not all are of the same quality, though. Nevertheless, they give us a good sense of what animates the artistic Indian mind. There seems to exist, despite all the linguistic divides and connecting themes, a certain common thread through art. Many of the artists have drawn scenes from their local legends; yet, one can feel at home with them.

Here are a few of those paintings:

This panel shows a Veena-playing Ganesha. In the background are other Ganeshas with all the musical instruments, even as an elephant calf looks lovingly at the deity.

In the panel below, one can say the artist is from Kumbakonam as the painting shows a Shiva temple with sharp features. Here, the Lingothbava is depicted. The adjacent panel (captured here partially) shows the line drawing various Shiva Ganas – his hordes.

Below, one can find a panel in which the divine permeates all existence where man worships the supreme with his wife, surrounded by a host of animals at a small wayside temple.

And note the array of painted panels – a bull being bathed with love and the sculpture of a lion over an elephant and a Shiva linga in the sanctum of a temple with the bull before him. Standing almost alone in the campus, looking at these panels, one can experience the power of art.

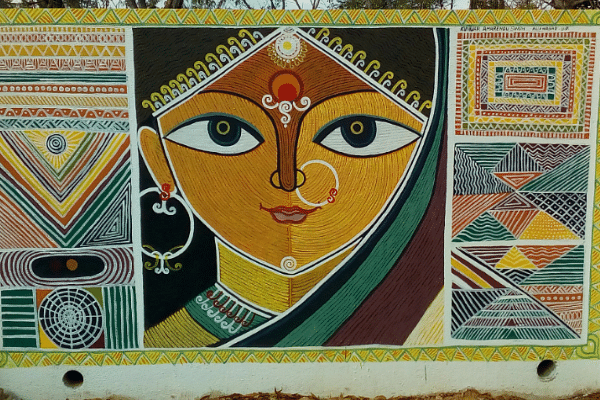

Note the Goddess Durga with a deer by her side – in archaic times, the deer, too, was her mount. Chilappathikaram, in its litany of the goddess by tribal worshippers, sings this form.

Here, we see an artist from Pudukottai of Tamil Nadu using the “Chitrakathi” painting style to depict Saraswati. I learn that Chitrakathi is also the name of the nomadic community which moves from place to place telling Puranic stories through their paintings. This is their style. They are known in Maharashtra, Karnataka, and Andhra Pradesh. So, when Anant Pai (“Uncle Pai”) named his creation Amar Chitra Katha, was he also connecting the reader to a persuasive memory of an Indic story with pictures and paintings?

Imagine you are alone in a vast landscape with all these paintings in the open and just birds for company. Each painting, a solitary reaper, says, “Watch us or gently pass.”

And you also come across some innovation. A muscular Rama mourns Jatayu.

And the geography of India fuses with the face of Shiva with even the Pakistani flag-like crescent moon and star adorning his matted hair.

Below is another interesting painting. The skylines are dark – suggesting the pollution that we have effected. Amidst the ocean arises Shiva and from his matted hair snakes drink out from the ocean. Or are they absorbing the poison that we have added to nature? A painting with dark lines and a deep suggestion indeed.

This folk painting from Assam shows Krishna dancing on Kaliya. When it comes to depicting love and romance across styles and languages, the artists choose Krishna – naturally.

Just the variety of Indian painting traditions which get introduced to the visitor through these panels is staggering. The possibilities of artistic experimentation and their display, not for Lutyens’ Delhi but for India, can actually increase the artistic sensibilities of society and also widen the base of the market for paintings.

Further, Indians of different linguistic states and cultures can understand the deeper cultural, spiritual, and historic bonds that unite them. It will reinforce the unity of India and substantially reduce cultural illiteracy. These panels show the power of art to remove regional prejudices.

Here are a few more regional art-based panels:

Note the Basoli painting (painting tradition of Jammu and Kashmir) showing the famous scene of one of the Krauncha bird pairs being killed by a hunter and which evokes empathy in Valmiki, which in turn makes him the Adi Kavi. Notice the outfit of the hunter. And notice the attire of the sage. Now, ponder the way our modern intellectuals speak of “Brahminical and tribal divide”. The painting shows the meaninglessness of such constructs. A vanvasi and a non-vanvasi in the eyes of Indic tradition were not seen as two opposing categories.

Here is another folk painting from Punjab and showing the Ahoi Ashtami celebration before Deepavali. Ahoi is a goddess, and she takes care of the welfare of the house and children. And here in this painting, she fuses seamlessly with Mother India.

One only wishes the campus realises the treasure it possesses. Efforts should be made to market these depictions in card form, thus turning it into great saleable memorabilia. It will also serve as a spark to promote cultural dialogue.