Pretty Women Don't Act Anymore

A vicious cycle is at work within the Indian film industry. Mainstream films rarely attempt to look beyond a woman’s physical beauty. Female actors bag assignments on the basis of looks not acting skills, leading to the creation of more stereotypes than ever before.

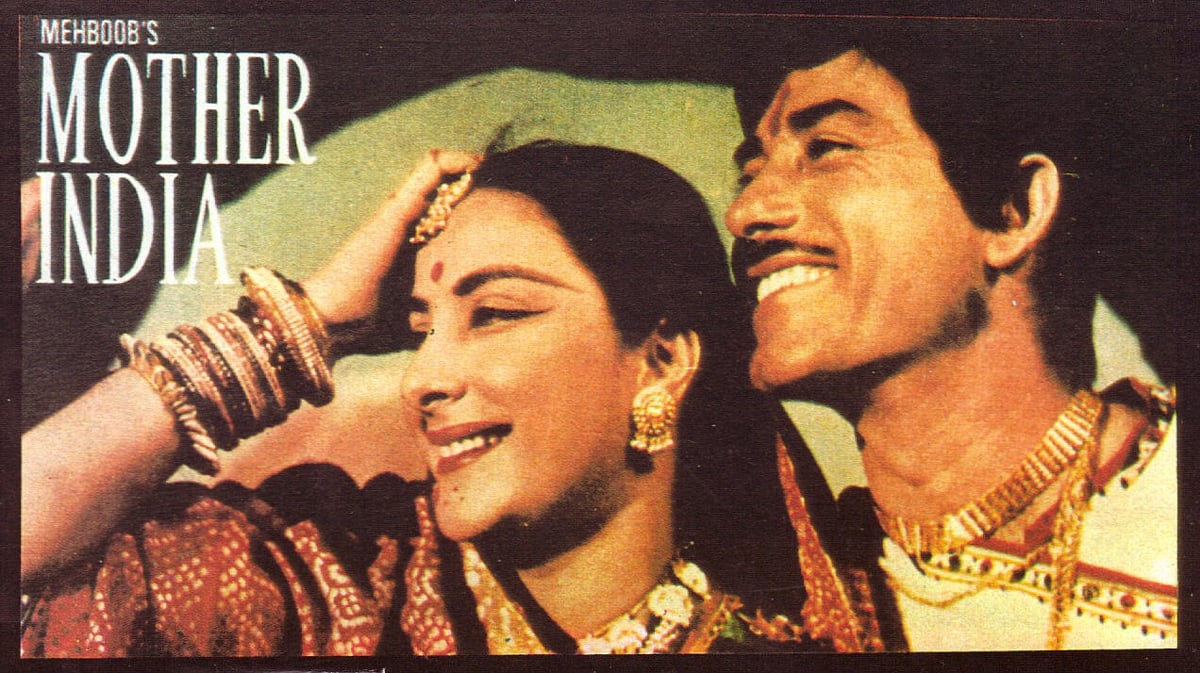

Mehboob Khan remade his own 1940 film Aurat as Mother India in 1957. Almost 60 years later, this Nargis Dutt starrer is regarded as the most significant among popular Hindi woman-centric films ever. The reckless usage of ‘woman-centric’ implies that the man-centric film is normal and the former is not, which is deplorable.

Films with women playing central characters are viewed as aberrations, which explain why they need to be categorized and manipulated to defend the indefensible: which is that the portrayal of the woman in films in cinema is regressive and stereotypical. That’s why whenever the subject of women in popular Hindi cinema comes up during a discussion; Mother India is usually the first one to return to our minds.

Not that gender inequality is unique to Hindi cinema. It is a global problem, although India’s performance on every count is seriously embarrassing. A first-of-its-kind study was conducted by the Geena Davis Institute on Gender in Media, UN Women and The Rockefeller Foundation, which analyzed the content of gender roles in 10 most profitable film-producing territories.

The case studies were ‘theatrically released between January 1st 2010 and May 1st 2013 and ‘roughly equivalent to a MPAA rating of G, PG, or PG-13,’ two conditions which led to deductions which dedicated viewers of contemporary Indian cinema across all genres and languages may not like to hear.

To start with, Indian films are among the worst in their emphasis on sexy attire and ‘some’ nudity. Even more pathetic is the focus on attractiveness, an area in which India has emerged as the global leader. While no sample study can be perfectly accurate, the nation’s cinema in general and Hindi cinema in particular doesn’t attempt to look beyond the woman’s physical beauty in mainstream films. Female actors bag lucrative assignments on the basis of looks as opposed to acting skills, leading to the creation of more stereotypes than ever before.

A typical example is Katrina Kaif, who has been trying to evolve into a decent actor for quite sometime. If beauty has to be admired, she will possibly score a 9 on a scale of 10. As an actor, how good is she?

Think Waheeda Rehman, Nutan, Meena Kumari, or Sridevi, Madhuri Dixit and Kajol, in spite of the many mediocre films they starred in. Katrina’s best moment as an actor may be as bad–or worse–than the worst of a Madhuri or a Waheeda Rehman. But she is one of the leading female actors at present. Enough said.

That the past has to be evoked during assessments of quality is a reflection of the flawed present in which objectification at the expense of content has reached new levels. No film in the modern-day counterpart of parallel cinema has been able to make the sort of impact that those with female central characters like Bhoomika, Mirch Masala and Arth did. Each of them had fine actors–Smita Patil and Shabana Azmi–and they delivered a significant sub-plot in the post-70s cinematic narrative.

An irony of modern times is that obsession with attractiveness is on the rise. Amidst such a decline, many in the media have been struggling to establish how more and more women are finding better roles in the Hindi film industry. Those supporting this argument must state that each year sees a rise in the number of releases from Mumbai’s film-producing factory. They ought to admit that the industry had never branded a film as a horex–or a film blending horror and sex–before Ragini MMS:2came along. This, they naturally don’t.

Since 2000, Madhur Bhandarkar has directed several women-centric films such as Chandni Bar (very good), Page 3 and Fashion (good) and the not-very-convincing Corporate and Heroine. While Bhandarkar deserves a special mention since his choice of subjects has attracted top stars like Priyanka Chopra and Kareena Kapoor in spite of the low budget of the films, he appears to have delivered his best with Chandni Bar, his second film after the disastrous Trishakti. Besides, none of these films really qualify as mainstream cinema.

Vishal Bhardwaj who is infinitely more talented than Bhandarkar has directed some films with strong female characters such as 7 Khoon Maaf and the controversial Haider in which Tabu’s is the key role around whom the story revolves.

Tabu is an accomplished actor who has played powerful characters in Astitva, Chandni Bar, Maqbool and even in the breezy but unambitious Cheeni Kum in which her character falls in love with a man, who is older than her father, played by Amitabh Bachchan.

Since she is 42, mainstream Hindi cinema will judge her as an actor who is past her ‘expiry date.’This eliminates the possibility of casting her as the central female lead–or the main supporting actor–in big budget films. Is this power?

Vidya Balan is being seen as an actor who can steer solo starrers after her fine show in Ishqiya and the success of Kahaani and The Dirty Picture. True, The Dirty Picture brought in more revenue than the producers might have imagined, but an honest analysis would suggest that a fair share of the revenue must have come from those who went to see a ‘dirty’ picture.

This argument can be substantiated by the fact that this film became the highest grossing Hindi film with an ‘A’ certificate, a record eclipsed by the sexist filth fest Grand Masti not much later. Kahaani was admittedly a success, in fact, a huge one for a film with an estimated budget of Rs 8 crore. That kind of money is equal to, or less than,the fee of a top male star or what he eventually earns because of his share in distribution rights.

Mary Kom, Queen, No One Killed Jessica, Mardaani and Gulaab Gang are among films with powerful women characters that we get to read about every day. Gulabi Gang, being a bad film, bombed, which is fine. Dedh Ishqiya didn’t live up to its hype, which is not new either.

But did any of the ‘hits’ come remotely close to earning Rs 100 crore in the Indian market at a time when the typical high-budget Hindi film with a Khan or Hrithik Roshan is targeting Rs 150 crore from ticket sales in India alone? None!

Did the producers shell out Rs 60 crore or more for any of these productions?

Forget spending that much, a film which stars a woman rarely manages to earn that much. Earnings explain a film’s reach or the relative lack of it. This reach, in turn, is the only way real power can be understood. Major male stars have that in abundance, but those with comparable stature among women don’t have a fraction of what the men do. Try as we might, this fact cannot be overlooked or disguised.

Within the film industry, a vicious cycle is at work. From day one, a big budget film is marketed as one with a big male star in the lead. Any insistence that a similar film with a Priyanka Chopra or a Deepika Padukone as the main star cannot be made because nobody has a story to sell is utter rubbish. The real problem is that directors are dependent on the money that producers invest.

Producers evaluate the risk factor and choose not to gamble because he won’t be able to find distributors who will shell out a much higher price. The ultimate outcome is the small-budget film which suffers because of ordinary marketing and is eventually released on a much smaller scale compared to the big-budget entertainer. Seekers of simplistic classifications call it an ‘art’ film.

Nobody asks a key question since it is seen as irrelevant.

If a commercial entertainer with a woman in the central role costs Rs 100 crore, will it manage to bring Rs 150 crore home if Bang Bang! can?

Logically speaking, that’s possible, although producers need to believe in the idea and invest first. Distributors must respond by buying the rights thereafter. Since that won’t happen anytime soon, a huge film in the traditional sense will lead us to one more Dhoom:3.

A big film with a female star will be another The Dirty Picture. Five times less reach as a sign of shifting balance of power?

That’s a bad joke.