The End of Multiplex Cinema

Co-opted by the mainstream, exploited by film makers who failed to raise enough money, what was once a bold new wave has lost its identity.

Sometime in the late 1990s, a new story started to unfold in Indian filmdom. PVR Anupam, a four-screen multiplex, was inaugurated in Delhi in 1997. Soon, similar islands of luxury were born in several major cities, allowing viewers with relatively deep pockets to make lifestyle statements by offering a better environment, facilities and cinematic options to choose from. Time went by. The media started talking about this phenomenon as the “multiplex boom” which promised to transform Hindi cinema by offering diversity to urban viewers.

Such a possibility was not an illusion. Multiplexes had small theatres with far fewer seats compared to the usual 1,000-seat single-screen monsters which charged film distributors much higher rentals and needed many more footfalls for viable returns. With some plex theatres having as few as 200 seats, renting them to showcase small-budget offbeat ventures was infinitely easier. Those who had invested in such entertainment-cum-relaxation centres weren’t sending out free screening invitations to low-budget film producers. But they had no reason for complaint.

Finding a producer had always been the problem for off-beat film-makers. Caught in a safety-first trap, most potential backers refused to finance films with no stars and mature themes which sought to present unusual ideas to niche urban audiences. Their approach frustrated directors who believed that exposure to serials and films from the West through satellite television had changed the mindset of a small (yet big enough) percentage of urban viewership.

Freedom-seeking directors like Anurag Kashyap ran from door to door in search of money to finance their projects. After many battles had been fought, most of which were lost, these new small theatres allowed this bunch of intrepid film-makers to create a genre which came to be known as “multiplex cinema” because of its content, budget, manner of presentation and modernity. And this new form impacted and transformed the feel of mainstream films in the not-so-long run.

However, soon came yet another change. Numerous films became part of the multiplex cinema movement simply because they were small-budget no-star productions. Meanwhile, mainstream Hindi cinema was growing up. This was happening really fast, which meant that a maker of an authentic multiplex film needed to stretch himself a little bit more which he often failed to do. But, intrusion of inappropriate films notwithstanding, questioning the contribution multiplex cinema has made to Hindi films is unfair.

Among the initial movers was Ram Gopal Varma, whose Kaun (1999) with Urmila Matondkar and Manoj Bajpayee was a sophisticated horror thriller. Light years ahead of films manufactured in Vikram Bhatt’s scare factory, Kaun terrified viewers as the two main characters engaged in an unpredictable game full of riddles. Three years later, Varma produced Road (2002) which borrowed from Hollywood but took the idea of the road movie in Indian cinema to a new level.

Did Shashilal K. Nair make Ek Chhotisi Love Story (2002) for the multiplex audiences? Maybe he did, maybe not. But the film did strike like lightning on a hot summer day. For these were days when masturbation scenes in a Hindi film about a young boy’s passion for an older neighbour (Manisha Koirala) were unheard of. Although Koirala would take Nair to court for using a body double to insert a few anatomy-revealing scenes without her permission, she had played her part by showing how Hindi cinema could do with some bravado in a changing climate.

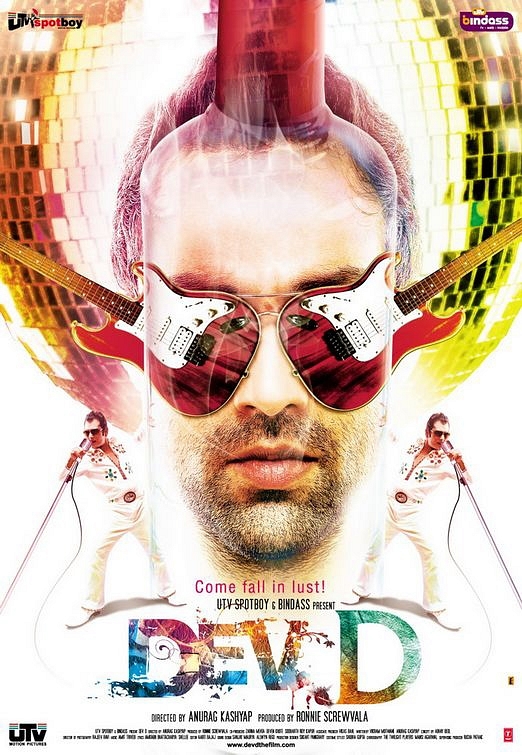

The crowd rapidly swelled, and the apogee of experimentation in the multiplex genre—as it was originally defined—was possibly reached by Kashyap in Dev D (2009) and Bejoy Nambiar’s Shaitaan (2011), both films distinguished by avant-garde cinematic technique, from narrative style to the use of music.

In the intervening years, two contrasting multiplex films which stand out are Reema Kagti’s Honeymoon Travels Pvt Ltd and Anurag Basu’s Life in a..Metro, bothreleased in 2007, with distinctly defined sub-plots which evolved within the broad structure of the films as independent narratives. Kagti dealt with stories ranging from two superhumans masquerading as human beings, to a a closet homosexual who marries a straight girl carrying the hangover of a failed relationship. The film was directed with a comic flair and easy restraint which worked.

Unlike Kagti’s film, Basu’s Life in a..Metro stayed away from humour for most of its running time. Its longest storyline involved a man in an extra-marital relationship. He doesn’t have quality time for his wife, who has left her job to look after their kid. The wife eventually falls for a struggling theatre artist but ends the relationship before crossing the final frontier. In the meantime, a young woman understands the deeper meaning of life with the help of a man she had absolutely hated when they had first met through a matrimonial site. In their different ways, both Basu and Kagti tried to define post-economic-reforms middle-class life, striking a chord with the urban viewer.

Hinging on a relationship that grows through an exchange of lunchboxes between two strangers, Ritesh Batra’s The Lunchbox (2013) is a minor classic. Marked by memorable performances by Irrfan Khan, Nimrat Kaur and Nawazuddin Siddiqui, and director Batra’s excellent helming, The Lunchbox merits the sort of applause not many classically multiplex films have deserved to get in recent years. But by this time, sensitive and innovative treatment of relationships was no longer the exclusive domain of the genre. Taking cues from the newbies, mainstream Hindi cinema had begun to take risks.

Barfi! (2012) is the journey of two people who eventually discover what each means to the other. The boy is lively, deaf and mute; the girl, autistic. Because of the star cast headlined by Ranbir Kapoor and Priyanka Chopra and an estimated budget of Rs 30 crore which is far more than the cost of a typical non-star film, Barfi! had to escape from the confines of metropolitan viewership and address a bigger audience. It succeeded, with the filmjoining the exclusive Rs 100 crore club in India alone.

Barfi!‘s viewership was predominantly urban. However, had the film capsized in smaller cities, going past the magic three-figure mark would have been extremely tough. With Barfi!’s success, the distinction between the multiplexer and the mainstream had turned into a blur.

Not that this had happened for the first time. Generalisation being a chronic disease which no medicine can heal, a brainless comedy like Maan Gaye Mughal-e-Azam (2008)becamea “multiplex film” because its limited budget resulted in a limited release. The fact is, the film was so terrible that even if it had a star-studded cast, pathetic direction and story would have flushed it into oblivion in small as well as big cities.

Humour in the genre peaked with Sagar Ballary’s Bheja Fry (2007). An adaptation of the French film Le Diner de Cons—“plagiarism” is a term used only to rubbish mainstream cinema—Bheja Fry accomplished the rare feat of making a viewer laugh throughout. This was made possible by a stellar turn by Vinay Pathak who played a naive man in love with his own voice.

Bheja Fry was a commercial success, but it made one ask whether this film indeed belonged to the genre. After all, had Govinda been hired to play the role and his untamed spontaneity kept in check by Ballary, he would perhaps have delivered a more accomplished performance than Pathak. But the budget would have shot up, and the film would have been released in a thousand theatres and more. The content would have remained unchanged, but the film would have become part of mainstream cinema.

By the time Bheja Fry released, the original meaning of the term “multiplex cinema” had become hazy. Anything with a small budget and no stars was apparently part of the genre. It now incorporated comedy, tragedy, thriller, romance, just about any kind of film. That many were driven by plots and treatment that were hardly offbeat had eroded the difference such films sought to make.

The core of Delhi Belly’s (2011) viewership came from urban areas; yet, everybody didn’t watch it for its racy plot. Dialogue littered with expletives and a track with an inviting catchphrase—Bhaag D K Bose D K Bhaag—is what did the trick, not the sort of target multiplex films sought to achieve. Kahaani (2012 ) was a sophisticated thriller. So was Talaash: The Answer Lies Within (2012 ) until it lost its way towards the end while retaining the feel of a noir film. Some described the former as a multiplex film, yet nobody declared Talaash as one because Aamir Khan starred in it.

Mixed Doubles (2006) had a bold theme: that of swapping partners to infuse some measure of sexual energy into marriage going stale. It ended with an escapist compromise; neither the husband who had initiated the move nor the reluctant wife had sex with different partners. But by this time, mainstream maharajah Karan Johar was also tapping the same vein. In fact, he took it way ahead in Kabhi Alvida Naa Kehna (also, 2006), a typically lavish Johar production in which two individuals in unhappy marriages surrender to passion and engage in extra-marital sex.

And if one were to talk about recent mainstream films which have shown pre-marital sex—a strict no-no till just a decade ago, it will start reading like a laundry list.

My Brother Nikhil (2005) made by Onir, an openly gay director, is perhaps the most sensitive Hindi film so far on same-sex love, and was certainly made for a niche audience. But for the masses, there was Tarun Manshukhani’s Dostana (2008). Though making a crass farce of homosexuality, this hardcore commercial film did comment on how most elderly Indians who viewed homosexuality with utter shock needed to define human beings on the basis of relationships.

Both Nagesh Kukunoor’s Iqbal (2005) and Aamir Khan starrer Lagaan (2001) centred around cricket and the victory of underdogs. Yet, Iqbal is classified in our heads as a multiplex film, while only a Martian would think so about Lagaan. The truth is that the original definition of multiplex cinema has fallen by the wayside years ago.

The pioneers of the genre created a revolution whose impact was much bigger than the revenues. They emboldened mainstream cinema to tackle themes it had shied away from earlier. But today, that bold and vibrant rebellion has lost meaning. After all, if any film with a small budget and no stars becomes a member of that pathbreaking family, every unknown neighbour will become a relative very soon. That is a terrible idea.