The First Tamil Hindutva Magazine

The Tamil Hindutva heritage lies in plain sight. All one needs to do is open themselves to it and they’ll see it in all its glory.

Tamil Nadu has a rich tradition of Hindutva of its own. Though a deeper phenomenon of Indic life, Hindutva in the present context is the resistance movement thrown up by the national life force against the predatory expansionism of monocultures.

It was a woman poet, Ganga Devi, who perhaps first showed the deep Vedic, and hence Tamil, roots of Hindutva when she wrote in the fourteenth century, CE, the poetic work Madura Vijayam or Vira Kamparaya Charitham. It speaks of how “the water of the river Tamraparani, which used to be rendered white by the sandal paste rubbed away from the breasts of youthful maidens at their bath, was now flowing red with the blood of cows slaughtered by the invaders”. It is a poetic criticism of the anti-woman veil system imposed by Islamist aggression, which at the same time was also destroying the Earth-bound spirituality of the nation symbolised by the cow.

So, a sword of resistance was raised. This was the sword of Siva – handed to the Tamil dynasties of Cholas and Pandyas, which was preserved by sage Agastya, to be handed in turn to Kampana. That sword of Siva, saved for generations by Agastya, who was the legendary primordial Tamil seer, and handed to Kampana by a goddess in the form of a woman walking into his court, in a way symbolises Hindutva. We see its splendour in the voice of Vallalar, who said Hinduism alone teaches the science of immortality while other religions, if at all they know of that science, are mere approximations. Ayya Vaikundar to Rettaimalai Srinivasan to Bharathi, Tamil savants opposed proselytising. In this regard, it is not astonishing that the first explicit Hindutva magazine of Tamil Nadu came from the southernmost part of the Indian mainland – what is today the capital of Kanyakumari district, Nagerkovil – more than seven decades ago.

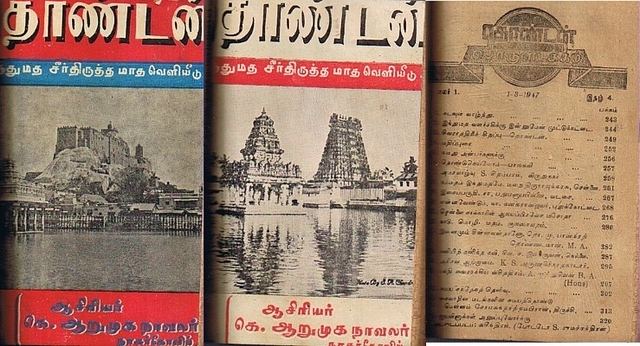

A serendipitous chance led to the discovery of an old bound volume of this magazine – six of them between 1946-47. The magazine was named Thondan, meaning “volunteer”. In the Tamil context, it meant one who provides services to people voluntarily. The name of the founder-editor was Arumuga Navalar, not to be confused with Arumuga Navalar of Eezham. The list of the names of those who had wished well for the magazine, is the cream of Tamil society of the time – the famous poet Kavimani Desigavinayagam Pillai, the eminent trade unionist Thiru V Kalyanasundaranar, and Tamil scholar C P Ramaswami Iyer, Marai Thirunavukkarasu, Shuddhananda Bharati, Ki Va Jagannathan, Namakkal poet Venkatarama Ramalingam Pillai and so on.

The messages sent went beyond the customary ones. For example, Bharati in his lyrical message, defines a “Hindu” as one who removes the misery of others and Hindu dharma as the ocean of bliss. He wishes the magazine to make Hindu dharma flourish all over the world. The Namakkal poet – the famous freedom fighter – wishes the magazine to revive the valorous tradition of Tamil Nadu and remove the “mental sickness of so-called atheists”.

As we read the magazine content, we find a debate on whether to use the revenue from Hindu temples for public education. The year was 1947. The editor of the magazine, one Ramanathan Chettiar, writes:

In the name of pubic schools, public hospitals and public student hostels, other religions are proselytizing Hindus in large numbers. Despite knowing the intention of proselytizers, the government which is supposed to take a neutral stand, is giving them financial assistance from the exchequer. From the surplus revenue of Hindu temples we too can run public educational institutions and nurture Hindu Dharma. Towards this end we need a Hindu reformist union under the government supervision to run such schools. Government should in a non-partial way provide the Hindu schools the same financial assistance it is offering to non-Hindu schools. Whatever services the other religions are providing, Hindus are more qualified to provide such services. Without doing this if the government continues its partiality while using the revenue from Hindu temples simply for public education, it will lead to the gradual destruction of Hinduism.

In the same magazine, another article written by Alladi Krishnaswamy Iyer, who would later become one of the members of the Constituent Assembly of free India, argues that the revenue from Hindu temples should not be used by the government for public education.

The magazine has a separate column titled 'Appreciations'. The temple entry proclamations made by Travancore, Ettaiyapuram, Malabar, and Kochi administrations are appreciated prominently.

On 12 October 1946, the Panchayat board under Sri Kanagasabapathy Pillai passed a resolution to open the Thiruchendur Subramanya Swamy temple for all Hindus. The 'king' of Sivagangai made a proclamation for temple entry at all famous temples, namely Thirukoshtiyur-Kallaiyar temple, as well as temples in Manamadurai province. All these proclamations are highlighted and appreciated. The magazine was clearly at the forefront of mobilising public opinion and the views of all sections of Hindu society in favour of temple entry.

The magazine had published a statement made by Malaviya on Noakhali riots. Malaviya had cautioned Hindu society against the complacency of feeling that they were the majority. “Such a feeling could be the death knell of Hindu society,” he had warned.

The magazine also published this announcement of Mukerjee’s in the background of the Noakhali massacre and the great Calcutta killings:

Today the very survival of Hindus in this nation is under threat. There is a need today to protect the welfare of Hindus, their rights and the self-respect of Hindu women. We need an organization of well trained fearless Hindu youths for this purpose - a national army of Hindustan.

The second issue of the magazine carries an important opinion-editorial. It is titled 'We are all Hindus!' I would consider this article an important document in the history of Hindutva in Tamil Nadu. Here is an excerpt:

The sufferings and problems heaped on us Hindus come not only from fanatic of other religions, but also from our own people. We know this from history. It was Jaichand whose tracery led to Islamist invasion. ... Not only then, even now same is the case. If we are to live we need to remove all the discrimination we have among us in the name of castes. In this regard it is not only untouchability but the feeling of separate castes, should also go. There is a tendency among a group of political leaders to blame only one community for the caste discrimination. How can such leaders create any unity in the society? These leaders also spew venom on Hindu religion and temples because of their hatred for one community. This only shows that these leaders suffer from inferiority complex and cowardice who lack self-confidence. Such people are claiming that they are Dravidians and not Hindus, for they have nothing but suicidal hatred towards Hinduism. Actually they are not interested in removing the discrimination but only interested in destroying Hinduism. ... Such people also go and talk in the Muslim League platforms. ...Why not these people actually fight against orthodoxy and work for reforms within Hinduism? That is what real reform movements in this nation do. Organizations like Saiva Siddhanta Maha Samajam, Saiva Siddhanta Publishing house, Arya Samajam, Vaishnava Samajam, Sri Ramakrishna Mission are doing such constructive work. Leaders like Mahatma Gandhi, Malaviya, Maraimalai Adigal. Sachidanandam Pillai, Venkitaswamy Naidu, Thiru Vi Ka - are all toiling for the same. And when we say orthodoxy do not think it means a particular community. All communities have orthodoxies and reformists. But the real paradox is that the Dravidianists because of defeatist mentality they suffer from had become real obscurantists and are supporting Muslim League. They oppose the nationalist parties and support the British. Let these Jai Chands of today leave Hinduism and become Muslims. We care not for them. But we who toil to reform our society and raise our civilization, we say with pride that we are Hindus!

This forceful proclamation against the Dravidianists of the day was made by Marai Thirunavukarasu – the son of Maraimalai Adigal, the progenitor of chaste Tamil movement. One of the foremost Hindutva voices against Dravidian racism was raised by the scholar son of Adigal!

The next issue of the magazine is quite stormy. It takes head on the orthodoxy opposing the temple entry movement. The editorial likens the orthodoxy opposing temple entry to the old lady who thinks that by brandishing her broom she could stop the ocean waves. Navalar further writes that those who consider themselves authorities of dharma should come forward and voluntarily proclaim their support for temple entry without waiting for legislation to impose it. A suggestion is made to give relief and financial assistance to Noakhali riot victims from the Tirupati temple funds.

Thondan has also published an article by Babu Jagajivan Ram. The title is 'Ever renewing eternal Hinduism'. Ram brings out both the agony of Scheduled Communities and their self-respect as Hindus.

We <i>Harijans</i> do not want to leave it to the so-called caste Hindus to decide whether we are Hindus are not. We have already taken a decision. We are Hindus and we are determined to remain as Hindus. I do not even like it that we are agitating for temple entry. I have great faith and love for the Hindu Gods and it pains me to think that <i>Harijan</i> entering the temples can pollute the Deities. Our Gods are not that weak. All I want to ask our orthodox friends is this: Has Hinduism come to such a low position that it does not allow its own followers inside the temple? You do not have to take the decision for the welfare of <i>Harijans</i>. You have to take a decision for the welfare of Hindu religion - for the complete goodness of the entire Hindu society. If we stand by temple entry then we show to the world that we are a religion that has vitality to renew itself. Otherwise we will be considered a dead religion. By standing by temple entry we can frustrate the British who are using every division in our society to further their rule.

Women, too, wrote in Thondan and very bold articles for their time appeared in that magazine. For example, one Rama Seethabhai from the port town of Tuticorin wrote an article on the 'Love of Gothai' (Aandal). The boldness is striking even for today:

Music arises from the organs of inner cognition. When these organs attach themselves to an object and become harmonized to that object, music emerges. He came with shining jewels on His blue coloured body. And in His lips He placed the conch shell and sounded His victory. And for Aandal at that very moment arrows of love come in torrents and make her feel agonized. That very moment she compares with the conch. How lucky that conch is! Will you not tell me dear conch! How great and sweet is the ambrosia from His lips!

Even as early as 1947, a Hindutva magazine discussed the so-called body-based poetry of Aandal – without compromising on both its sensual dimension and spiritual core – and a woman wrote it! A series on Indian science mentions Satyendra Nath Bose, clearly keeping itself updated with the latest science developments. (There is also the fallacy about ancient technology, but then, given the textual availability of the period, it could be understood.)

This pre-independence magazine even assures that when India gets independence, leaders like Jawaharlal Nehru will make sure India achieves its glory in science.

February 1947 saw in Madras a Hindu conference inaugurated by Govardhan Sankaracharya. The head of the conference was Sri V V Srinivasa Iyengar. The conference passes a resolution demanding the cessation of temple entry. The conference demands that at least four temples – Bhadrachalam Rama temple, Tirupati Venkatachala temple, Kanchi Varadaraja temple, and Triplicane Parthasarathy temple – be exempted from temple entry. Thondan harshly criticises this stand: “Are these four temples going to be the Pakistan of orthodoxy?”

There was also activism at ground zero. Thondan reported on April 1947 about proselytisation attempts by evangelists of the Scheduled Caste community families near Thirukazhukundram. Thondan uses the term 'Aadhi Hindu' (aboriginal Hindu) instead of 'Harijan'. A primary school teacher of the area who was also an evangelist, had told families there that if they converted to Christianity, he would be able to get for them land from the British government and Rs 200 per person.

As a first step to prove their conversion, he asks the families to demolish the 'Gangai Amman' Goddess temple and build a church there. However, a youth, one Gothandaraman, told Marai Thirunavukkarasu about this. So he went there and held talks with the family. They told him about the problems they faced at the hands of certain so-called caste Hindus. After the talks with all sections of society, they tore the agreement they had made with the evangelist. Further, they made it clear that they would live their lives as Hindus. A committee consisting of Kothandaraman and some eminent citizens, was made to take care of the problems of the people in the area.

We learn from the old pages of the magazine, now fast getting discoloured, that there was even a programme to train Tamil Hindu youths as pracharaks for dharma. There is a question-answer section and there are cartoon-like illustrations. There is a cartoon supporting temple entry. The gods and acharyas bless temple entry from the sky while a small group of orthodox people oppose it. Unfortunately, that page is too damaged to be scanned. Here, we see a picture depicting the contrast of a government temple board affluent with revenue while temples are in a dilapidated condition – yes, that was in 1947 and it could as well be talking about temple conditions today.

Another cartoon shows Hinduism as a sleeping saint and Thondan as a boy volunteer awakening him, blessed by gods and acharyas. This cartoon is titled ‘Thirupalliyezhuchi’ or Suprabatham.

We don’t know what happened to this noble endeavour – why it stopped. But there is one thing I know. If today in Kanyakumari district there is a socio-political awakening of Hindus like nowhere else in Tamil Nadu, it is because of the punya-bala of such souls. In fact, Tamil Nadu can get its inspiration from such great savants who dedicated their lives for the cause of dharma and society, from Iyya Vaikundar to Thanulinga Nadar to Swami Madhuranantha Maharaj.

Hindutva in Tamil Nadu is like a river perennially running right under your feet, unknown to you, yet sustaining life even in times of scorching drought. All one needs to do is realise the great Tamil Hindutva heritage that is in plain sight, and then the river will surface with a life-rejoicing fury that all the pollutants accumulated during the Dravidian eclipse of Tamil land would be cleansed forever.