Kargil: How Much ‘By The Throat’ Did The Pakistan Army Have Us?

Pakistan Army’s claim that it had caught ‘India by the throat’ in Kargil in 1999 is absurd. Here, Lieutenant General (retd) Syed Ata Hasnain explains just how wrong they are.

In 1995, I was in Leh and tasked to attend a war-game of the Kargil Brigade. In the course of doing so, I happened to ask the very competent Brigade Commander, late Brigadier Sandeep Sen, as to why a 120-kilometre frontage in the mountains was being held only by a brigade. He gave me an astounding answer, which I quote:

...this is the concept of traditional gaps; it is a quid pro quo kind of understanding (unwritten) that deployment can be light on both sides and neither side will exploit an advantage.

He explained that this being a Shia-dominated area, irregular operations were not suspected to take place because the support base was firmly with India. In 1997, Pakistan commenced deliberate shelling of Kargil sector targeting even the road from Zojila leading to Leh. It was testing of the waters.

The occupation of the heights vacated in winter across the Line of Control (LoC) in 1998-99, even as India’s peace dialogue with Pakistan’s civilian government was underway under prime minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee, was ostensibly planned by Pervez Musharraf, the army chief. I dare to say, I share one thing in common with Musharraf; he and I are both alumni of the United Kingdom’s iconic institution, the Royal College of Defence Studies (RCDS).

Did Musharraf’s ploy really have the Indian Army and the nation by the throat as he boastfully states, is the question under debate. Analysis of this has to begin with the presumed aim of the mission Musharraf undertook.

In 1999, Pakistan was concerned about flagging militancy in Kashmir and the possibility of the international community losing interest in it. The nuclear test of 1998 had exploded the clandestine Pakistan capability and Pakistan was on virtual nuclear parity with India thus emboldening it to risk a conflagration. Considering the Pakistan Army’s diluting power within Pakistan’s polity and its ever-present desire to be the ruler, Musharraf could not allow the India-Pakistan peace process to seriously take off.

For the Pakistan Army, tension with India promotes its own political power and importance, and Musharraf was not short on political ambition either. His perception was that a secured military advantage in a limited skirmish along the LoC in a remote area may not instigate India into launching an all-out war; the nuclear balance was anyway in place, as per his mind, thus probably enhancing India’s limit of tolerance by a few notches. He could thus play a few ‘games’ within that level of tolerance.

The area Musharraf chose was the same which late Brig Sandeep Sen described as the sector with "traditional gaps". As far as Musharraf was concerned, there was nothing traditional about it. It gave Pakistan the advantage of strategic surprise. The posts were vacated in winter by the Indian Army and only reconnoitered by air. Occupation of these would provide the distinct tactical advantage of domination; anyone who knows high altitude (HA) operations can assess that to dislodge a well-entrenched defender at these heights would need an advantage of 9:1.

The Indian Army would have to push in reserve formations to achieve anything near that ratio and the reserves would be unacclimatised to HA operations thus elongating the response; besides of course, upsetting the order of battle of flanking formations.

Most important of all, the main logistics route to Leh ran close to the LoC in the Dras-Mashkoh sub-sector in the general area of Kargil sector. Interdicting this artery meant that winter stocking of Lima sector (Ladakh sector including Siachen) would be adversely affected.

The alternate route from Manali via Upshi to Leh had limited capacity because of the nature of terrain and early closure for winter. Logistics choking of Lima sector in the perception of Musharraf would mean the inability to sustain deployment in Siachen thus forcing vacation without firing a shot.

Musharraf had other linked intentions too. One, to bring Jammu and Kashmir into limelight again and two, to trigger greater dynamism in the militancy in the valley. Concerns of the international community would run high as there was little clarity on nuclear doctrines and protocols of the region. The forced movement of reserves from the valley (immediate flank) would open vast spaces for conduct of militant operations and infiltration.

In discussions with Pakistani officers a year later in a strategic programme abroad, I did admit that Musharraf’s plan was bold but just as the Pakistanis have always historically done, they ‘mastered the initiation and had no clue about termination’. Here is how I justify this statement.

Was the Indian Army taken by surprise? Admittedly, it was but in conflict that is always possible. The more important issue is how it reacted thereafter. 15 Corps had an operational responsibility from Demchok to Gulmarg along the LAC, AGPL and LoC, with Siachen and the militancy in the valley to contend with. It was not the best of arrangements with 3 Infantry Division in Lima sector at lower priority as the militancy in the valley and ongoing infiltration grabbed all the attention.

Initially, 15 Corps treated the intrusions as a local problem but as already explained, recapturing obnoxious heights in HA areas is virtually impossible unless you are prepared to fight attritional; for that you need troops.

The well acclimatised units de-inducting from Siachen were in different stages of rest and relief, strung out over the Lima sector. While they were available as unit entities there, bayonet strength hardly exceeded half the strength units usually deploy for offensive operations. There was no option but to induct 8 Mountain Division which was deployed on the counter insurgency (CI) grid in North Kashmir. Pulling a divisional size force from CI operations involves re-orbatting and reorientation.

It is to the credit of the resilience of 8 Mountain Division under Maj Gen (later Lt Gen) Mohinder Puri, an astute Infantry officer, that the division could redeploy in such a quick time frame to the HA area of Dras. This move in driblets was under observation and shelling throughout, once Zojila was crossed. Space was a major constraint in the narrow corridor between the LoC and the Zojila-Kargil road. In the interim, the Indian Air Force had already stepped in followed by the redeployed artillery which kept the Pakistani positions under constant punishment.

Musharraf possibly perceived that this would be the limit of our response. His troops could withstand this by occupying reverse slope positions by day and the nooks available in the broken terrain. However, once the virtual tactical pause, forced by the time required to redeploy 8 Mountain Division was over, there was no holding back.

Waves of Indian infantry undertook daring assaults in almost complete attritional mode, employing multi-directional approaches simultaneously to divide reaction and exploiting success on any single approach to capture crucial objectives. In retrospect, could this have been done more smartly by isolating objectives and forcing surrender without contact battles?

Military prudence normally demands minimum application of force to achieve maximum gains. However, the Indian commanders were under pressure. The nation was getting a little impatient, and success in the capture of a few important heights visible to even the media would raise morale, reinvigorate confidence in the army and most importantly send home the message to Pakistan that India would go to any length to restore the sanctity of the LoC.

There is no doubt that the passion, courage and guile of the Indian infantry and artillery restored the situation living up to the then Army Chief’s statement that the Indian Army would fight with what it had. At no time during the approximately 10 weeks that the operations continued was the Indian Army so hamstrung for options that it could be perceived that the Pakistanis had it by its throat.

Those unaware would need to be informed that by the end of June 1999, the Dimapur based 3 Corps was already in Northern Command as was the strategic reserve mountain division. Their deployment gave Pakistan the shivers of the possibility of India broadening the frontage of contact thus preventing any reinforcement of the Kargil sector beyond the five Pakistan Northern Light Infantry units initially deployed.

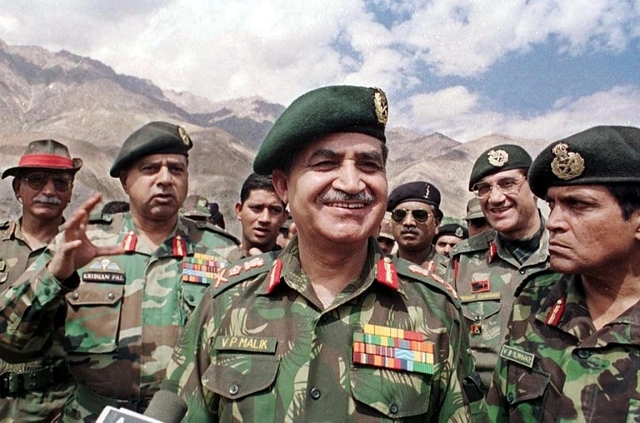

With the looming presence of these reserve formations and Pakistan ill prepared for a larger war because of the need for secrecy of its Kargil misadventure, it was actually Pakistan which had its throat in a noose. Masterfully, General Ved Malik’s responses and prime minister Vajpayee’s mature political handling kept Pakistan on tenterhooks forcing prime minister Nawaz Sharif to immediately head to Washington to plead with president Bill Clinton for pressure on India for closure of operations.

While most analysts concentrate on the immediate Kargil front for analysis of effects, they rarely look at the valley sector, where the impact of Kargil operations was most felt. It is not known whether Musharraf ever contemplated the kind of effect he achieved or was even aware of it. The vacation of North Kashmir by 8 Mountain Division led to its takeover by the Victor Force of the Rashtriya Rifles (RR), in addition to its own responsibilities in South Kashmir.

While 8 Sector RR moved from the North East to fill part of the void as did a brigade of another North East formation, the resultant time needed for orientation and initiation of operations in the crucial Lolab-Handwara-Sopore belt led to the loss of operational space which took time to regain, giving a spurt to militancy in the valley.

For recall, it may be worth the while to remember that the first of the suicide terrorist attacks commenced at this time and the reinvigorated campaign was rumoured to have been commanded by an SSG officer who had apparently infiltrated Handwara. It was the Rashtriya Rifles Kilo Force, which was newly raised to replace 8 Mountain Division that ultimately regained control under Maj Gen (later Lt Gen) Nirbhaya Sharma, the current Governor of Mizoram.

Musharraf’s military maturity is questionable if he feels so gleeful about having his adversary by the throat and not having decapitated him. That the adversary could respond and defeat the entire effort is a display of poor operational and tactical acumen; the strategic acumen need never be debated in relation to Pervez Musharraf, if it takes an Indian Army General to tell him where he actually succeeded.

Lastly, it should be China which should be unhappy with Musharraf. His botched operations led to the separation of Lima sector from the operational responsibility of 15 Corps (Srinagar) and raising of HQ 14 Corps which is now dedicated to look after Eastern Ladakh, Siachen and Kargil, thus optimising India’s military capability in these crucial areas, one of them being on the Chinese front.

A version of this article was published on this website in 2015.