Budget 2020-21: Modi Didn’t Shoot For The Moon

With Budget 2020, the Modi government has lived up to its track record of producing boring budgets and then doing the exciting stuff in-between.

The gap between what the Economic Survey promised and what was delivered probably explains most of the market’s gloom.

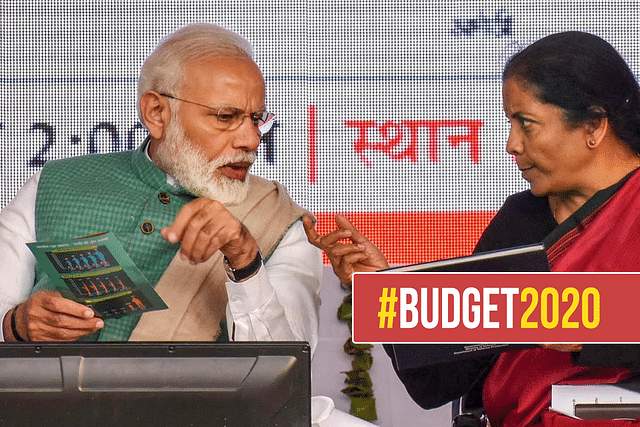

Given the huge expectations built up around Nirmala Sitharaman’s second budget, the marathon speech she delivered today (1 February) — perhaps one of the longest ones delivered by any Finance Minister in recent memory — was underwhelming. She could have made it shorter, sweeter and more focused. Alas!

The Modi government has lived up to its track record of producing boring budgets and then doing the exciting stuff in-between.

Corporate tax cuts announced in the budget of the 2015 were doled out in dribs and drabs till the government suddenly decided that it would offer the full loaf and more last September. Bang!

The Finance Minister has been making announcements on steps to revive economic sentiment and reverse the slowdown almost every fortnight since then, but the budget she presented for 2020-21 managed to disappoint. So, whimper!

One can say it was an opportunity missed, but when the big bang decisions come at other times, one can only conclude that the government treats the budget exercise as an opportunity to make longish political statements, not to spell out its economic vision and take bold decisions — at least in the budget.

You know this when the Economic Survey produced by Krishnamurthy Subramanian evinced more interest than the budget presented today.

The gap between what the Survey promised and what was delivered probably explains most of the market’s gloom.

That said, this budget has a few highlights that appear understated, even unexplained — and hence worth commenting on.

First, there is the direct tax amnesty scheme that is not quite an amnesty. Sitharaman said: “Currently, there are 4,83,000 direct tax cases pending in various appellate forums…I propose to bring a scheme similar to the indirect tax Sabka Vishwas for reducing litigation even in direct taxes. Under the proposed ‘Vivad Se Vishwas’ scheme, a taxpayer would be required to pay only the amount of the disputed taxes and will get a complete waiver of interest and penalty provided he pays by 31 March, 2020. Those who avail (themselves of) this scheme after 31 March 2020 will have to pay some additional amount. The scheme will remain open till 30 June, 2020.”

This is interesting. In each of the three actual amnesty schemes — one in 2015 and two in 2016 — the tax rates were so high that few actually bothered to take up the offer. But this time, the attraction is that you pay only the demanded amount and no penalties.

Assuming that the demands pertain to some years ago, the current inflation-adjusted value of that outstanding demand amount would be much lower, and hence the effective tax rates will be extremely favourable. Modi is delivering in this amnesty scheme something he could have done with his previous schemes.

No estimates were given on the scale of the amounts under dispute, but it is estimated to be in excess of Rs 8 lakh crore. If even one in eight litigants chooses to pay up, that would bring in Rs 1 lakh crore. That’s not peanuts.

Second, there is the cut in personal tax rates for the middle classes, but with riders. The expectation was that Sitharaman would indeed cut rates, but within the existing three-rate slab structure.

Instead, what she has given us is a seven-slab structure for those willing to forgo tax deductions. The surcharges remain.

There is, of course, the old tax-free bracket of up to Rs 2.5 lakh. But the exemption given for those in the Rs 2.5-5 lakh bracket this year (fiscal 2019-20) is gone, and the 5 per cent tax rate is back. But rates have been cut for incomes up to Rs 15 lakh in slabs of Rs 2.5 lakh each. Thus the Rs 5-7.5 lakh slab gets 10 per cent, the Rs 7.5-10 lakh bracket 15 per cent, the Rs 10-12.5 lakh 20 per cent and the Rs 12.5-15 lakh bracket 25 per cent.

For those earning above Rs 15 lakh, the old tax rates remain. Those who prefer the old tax deductions (under 80C, etc) can pay the current higher rates, including surcharges. Modi clearly loves the middle class more than the rich.

What this new structure implies is that you now have to choose between not claiming deductions under the old system and the tax cuts. This scheme will benefit those who were not investing in homes with borrowed funds or investing in avenues which gave them a deduction from tax (80C etc).

The tax consultant is back in business.

A third noteworthy initiative was the government’s decision to list the Life Insurance Corporation (LIC) through an IPO, which almost went unnoticed in the general gloom of the markets.

But that is a future big-bang dismissed with just a line in the budget speech. An LIC that gets listed will probably have a valuation in the range of Rs 5-7 lakh crore, if not more, given its overwhelming dominance of the life insurance markets.

But the key question is whether there is anyone who can invest at these valuations, especially when they know that the government will never let go of its cash cow.

The fourth gambit was a reversion to the old dividend tax system. Under the dividend distribution tax (DDT) scheme introduced by P Chidambaram more than 20 years ago, companies paid DDT on distributed dividends, thus paying taxes both on profits and dividends.

On the other hand, people who were not required to pay taxes had to do so indirectly (with the company paying the DDT). DDT is now gone, and the dividend is taxable in your hands at your appropriate tax bracket.

The markets were probably disappointed by this since they wanted dividends to be completely free from tax.

Expectations on the abolition of the Long-Term Capital Gains (LTCG) tax were also belied. Little wonder, the Sensex crashed by nearly 1,000 points, and the Nifty by 300.

Some global concerns over the Coronavirus also played out, but the market will recover in the coming days, as the budget actually has no devil in it.

The devil clearly was in the expectations built around it after last September’s massive corporate tax cut.

The expectation was that the government would take a big risk with the fiscal deficit, boost spending in infrastructure, pep up consumption, and cut taxes on capital gains.

Some of that was indeed on offer, but the changes are incremental, not revolutionary.

Modi lived up to his conservative instincts. The market had probably hoped that he would shoot for the moon. He didn’t.