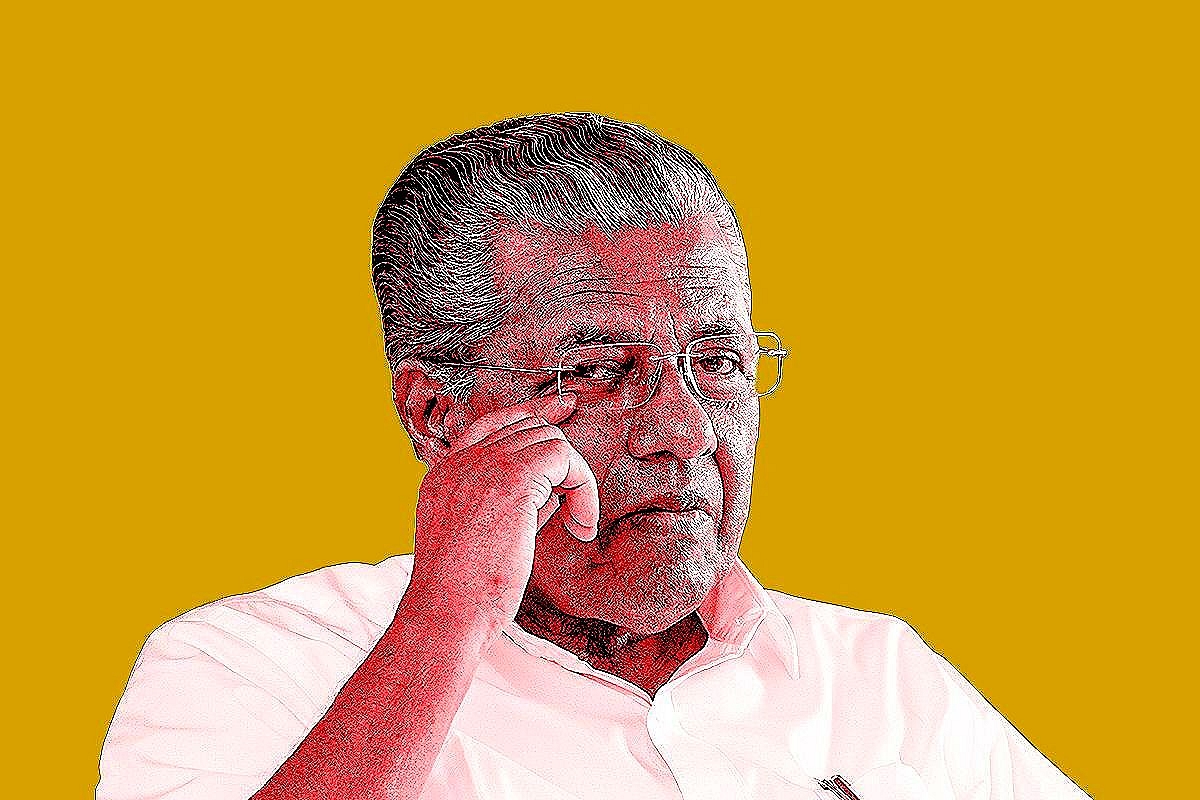

Covid-19 And Kerala: What Is Pinarayi Vijayan Flattening — The Curve Or The State?

By not accepting that a stony broke Kerala needs reforms to welcome capital, and being cagey about revealing the actual Covid cases in Malappuram district, Pinarayi Vijayan is shooting his people in the foot.

Numerous inconsistencies and contradictions, of both data and policy, were identified in a preceding article on Pinarayi Vijayan’s handling of the epidemic in Kerala.

A lack of adequate testing was highlighted, along with the lacunae this paucity posed, in spotting asymptomatic carriers of the Coronavirus.

The rate of sample testing went down in April, as did the number of individuals under surveillance, leading to uncertainty over reported case numbers.

This correlated with a surge of cases, first in late-April, and then again in May.

Specific doubts grew over the magnitude and nature of precautionary responses in Malappuram district in particular.

These were characterised by an inordinately high number of symptomatic hospitalisations for relatively few positive cases.

This was rather odd when compared to the lack of a similar response for a similar situation in other districts, and was compounded by Vijayan’s inexplicable reluctance to discuss case details from Malappuram district.

The net result is that Vijayan’s claims of having successfully flattened the curve appear suspect.

This approach has put Kerala’s already-fragile economy in a cleft-stick situation. Compared to other states, the case numbers may appear low enough for lockdown restrictions to be lifted.

Yet, they remain riddled with enough inconsistencies, and an appalling lack of testing capacity, to make a hasty return to normalcy a risky proposition.

Therefore, if the people of Kerala are to exit this tragically enervating limbo soon, and get back to making and spending money, it is important that the political exigencies and economic implications of Marxist laxity be scrutinised.

The economics first: The most conclusive indicator of Kerala’s return to normalcy will be when Lulu Mall in Kochi starts buzzing again. That is because this mall, in the state’s commercial capital, represents both the miniscule domestic segment of a classical remittance economy, and the bare revenue necessities of a firmly-bankrupt state treasury.

After 60 years of Marxism and socialism, Kerala is at a stage where most of the money spent in the state is generated outside it, and most of the money spent by the state, is on itself.

As a result, state revenue is largely restricted to five main sources — lottery tickets, liquor, petroleum, duties (like stamp or professional taxes) and the state’s share of GST.

Most of these are ‘funded’ by government salaries or foreign remittances. There is no industry of worth, agriculture is exempt from taxes, the bulk of the electricity it consumes is imported, and fisheries, once a lucrative sector, is presently in a mess.

Consequently, unlike in industrialised and energy-sufficient states, a lockdown means that Kerala’s revenues have shrunk to a trickle.

And the worst affected amidst that are numerous local services, and small-scale manufacturing sectors (like self-employed handymen or handloom garment units), which have grown on the fringe of remittance spending.

So now, we have a situation where the state earns little revenue unless retail spending recommences (with Gulf money), and where those few Kerala-based wealth creators, whose entrepreneurship adds the only substantive element to a microscopic economic base, are staring at a nasty disruption to their business plans.

This is the actual, pervasive effect of a lockdown (and the uncertainties surrounding it), which should have ended by now, if only the Marxists had managed things with a bit more vim.

To make matters worse, reduced revenues means reduced resources to tackle the epidemic — a reality reflected in the laborious rate at which testing capacities have been built up in Kerala.

It also means a further-enfeebled inability to bring the economy back on track (whatever little there was of it in the first place). The net result, then, is a downward spiraling vortex, with the epidemic and an empty treasury churning Kerala in the froth of ineptitude.

Worst of all is the deeper truth: the Pinarayi Vijayan government probably understands Kerala’s fundamental, structural fragility far better than a Swarajya reader, but will do nothing about it, because fixing the economy means junking ideology.

It is a fatal flaw of wanting to have the dogmatic welfare cake and eat it too. That is why Kerala’s finance minister, Dr. Thomas Isaac, chose with Pavlovian dispatch on 17 May, to cut Kerala’s nose to spite a reformist face.

Earlier in the day, Union Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman declared that a state’s borrowing limit was being raised to a whopping 5 per cent of its GSDP (gross state domestic product), to aid states in overcoming their cash flow and revenue-truncation problems resulting from the lockdown.

This option, she said, was contingent upon states passing necessary legislation to reform key sectors like labor, land and ease of doing business.

Necessity, it seemed, was also to be the mother of long-overdue change.

But Isaac’s response was that, while they needed the money, the Communists would not compromise on their ideology.

So here was a man placing an outdated, invalidated, discredited ideology over the pressing needs of 35 million people in dire straits.

There are no words to describe his stance, for, if this is how the state is actually being run, and this is the fiscal sinkhole being created, then the epidemic is probably the least of one’s worries.

The political aspects, though, are a lot easier to define:

Much of Pinarayi Vijayan’s pussy-footing around Malappuram district data has to do with the Muslim vote. Without it, the Communists have no hope in a godless heaven of retaining the popular mandate next year.

This was already evident in the 2019 general elections, when the Congress-led UPA swept 19 out of 20 Lok Sabha seats. Even the sole Communist victory in Alappuzha was a fig leaf margin of 9,213 votes, and that too only because both sides put up Muslim candidates in a constituency with 70 per cent Hindus.

Now, while the epidemic’s spread, courtesy the Tablighi Jamaat, did worsen traditional prejudices, divides and stereotypes, the ongoing public discourse remained demonstrably mature enough to make a distinction between Muslims as a whole, and those members of the Jamaat, who behaved irresponsibly.

People resigned themselves to the facts, and stuck to calling out Left-Liberals who sought to absolve the Jamaat of their mistakes.

The only thought, intuitively, was that one would have expected Malappuram district to report a larger number of cases, since that is what happened in the rest of the country.

Instead, the number of symptomatic hospitalisations shot up there (on last count, by far the largest in the state). This, allied with a drying up of patient details, is what caught people’s attention.

The statistical probability of so few cases in that district, in spite of so many hospitalisations, became an anomaly too strong to ignore.

Pinarayi Vijayan needlessly aggravated these suspicions by being cagey about details of Malappuram district, leading to doubts on true virus containment success. This has in turn cast a shadow on the good work done in March, and formed a cloud over how and when the curve will finally be beaten.

Hence, the question, with millions of livelihoods and an empty treasury at hand: Is containing the epidemic less vital than adhering to the Marxists’ First Law of Selective Atheism: that all Gods are false, save those of registered electors whose votes count in a tight fight?

If this is true, then it is ridiculous, because now, Vijayan is going to have a tough time stuffing the genie back into the bottle. One reason is that as on date, Malappuram district has the largest number of positive cases in Kerala. Second, this is happening exactly as feared, and precisely when Vijayan has yet to ramp up testing.

Third, his treasury is already out of cash to pay for next month’s salaries and pensions, while he needs a large sum to contain the epidemic. And fourth, his finance minister has just set new standards in senseless obduracy, by declaring that Kerala would not avail of much-needed funds at the cost of Marxist ideology.

To top it all, grave discrepancies remain unresolved. One is the Revolutionary Socialist Party functionary in Kollam district, who didn’t make the list, even after it was reported on 30 April that he had tested Corona-positive in a Kollam district hospital.

Another is Vijayan’s baffling decision on 28 April, to send the samples of 25 positive cases for re-testing, instead of reporting them. Nothing verified has been heard of these matters since.

What is a conclusion here, then? That Vijayan hasn’t the money, the executive will, or the political inclination to set things right?

Comprehension of modern economic theory might be a tall ask, for Marxists with a congenital tendency to blindly put the welfare horse before the growth cart; nonetheless, Vijayan has to understand at some point soon, that the only way Kerala will recover is when retail resumes in full swing.

If a remittance economy is to flourish, it can only do so when foreign earnings are spent domestically. And the only way that can happen, is if the epidemic is actually contained.

So, unless the Marxists get their act together, people will continue to ask only one question during lockdown 4.0: Is Pinarayi Vijayan trying to flatten the curve or Kerala?

Also Read: There Are Inconsistencies In Kerala’s Covid Numbers And That Has Dangerous Implications