Explained: How Aadhaar-Enabled DBT Programme Rescued The MGNREGS

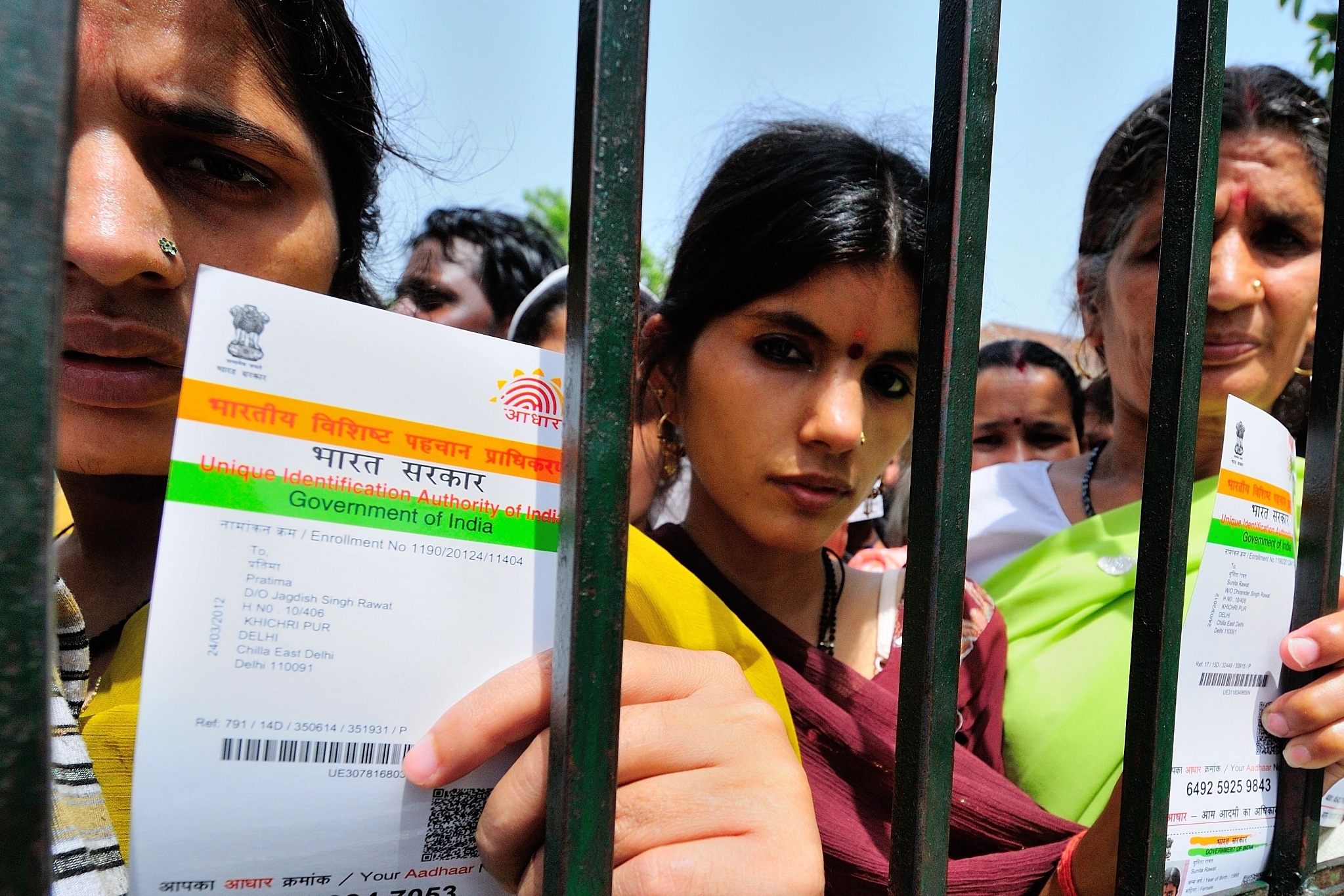

Today, of the 11.61 crore active workers under the MGNREGS, around 10.16 crore workers have their Aadhaar cards linked to their respective bank accounts.

It will not be an exaggeration to say that the MGNREGS has been rescued by a well thought out DBT system.

The Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (MGNREGS), enacted through an act of Parliament in 2005, was instrumental in curbing rural distress. Structured on the ‘food for work’ principle, a model that finds mention in Kautilya’s Arthashastra, the scheme ensured at least 100 days of manual labour at minimum wages for anyone enrolled in rural areas.

Thus, the objectives of the programme were twofold. One, the curbing of rural distress by guaranteed employment, and two, the creation of assets that could fuel gender equality, social inclusion, growth, and societal security.

Made effective from 2006, the first decade of the MGNREGS was plagued with corruption, monetary leakages, and political disruptions. The biggest problem, however, was that of delayed payments which rendered the entire programme pointless.

The problem of delayed payments drove many workers away from the MGNREGS. Given that the rural population was dependent on regular cash flow during the distress to meet their daily consumption needs, the delayed payments not only pushed workers towards manual labour outside the programme but also forced them to work at wages lower than what they would have earned under the MGNREGS.

The delayed payments were not only alienating workers for whom the programme was designed in the first place, but also adding to the rural distress by curbing liquidity and potential demand.

The Pre-Jan Dhan Era Versus Post-Jan Dhan Era

Before 2015, more than 650 million people in India were without bank accounts. Therefore, for the transfer of payments under the MGNREGS and several other welfare schemes, the government had to rely on panchayat bank accounts. Further, the workers were required to collect their wages from the gram panchayat office in cash.

This resulted in two problems. One, monetary leakages, and two, the connectivity. As per the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), in March 2014, there were 115,350 banking outlets across villages in India. The problem of delayed payments along with that of geography further alienated many more rural workers from the MGNREGS.

Today, every fourth person in India has a bank account. With more than 350 million accounts under the Pradhan Mantri Jan Dhan Yojana (PMJDY), the National Democratic Alliance (NDA) government, in its first tenure, ensured that every household had access to a formal financial instrument. Today, these accounts hold close to Rs 100,000 crore.

From 115,350 banking outlets in March 2014, the villages across India now have over 569,000 outlets. However, bank accounts served only a part of the solution. With Aadhaar, the government ensured that each bank account under the PMJDY was connected to an Aadhaar card, thus solving the problem of beneficiary identification.

The last piece of this holy trinity was the mobile phone. With cheap smartphones and data costs, rural workers had the option to access banking facilities from their mobile phones. The issue of over 275 million RuPay debit cards also enabled the withdrawal of funds from any of the banking outlets and ATMs.

With the National electronic-Fund Management System (NeFMS), the central government credits the wages of the workers for the MGNREGS under a bank account opened by the state government. For the authorisation of wages, only this state-level bank account is used.

Today, NeFMS is used by 24 states and one Union Territory.

While in the pre-Jan Dhan era the payments from the centre for MGNREGS had to go through the state, district, block, and gram panchayats before being made available to the worker. In the post-Jan Dhan era, the payments are directly credited to the beneficiary’s bank accounts from the funds credited by the Centre. The middlemen are gone for good.

The government is now using Aadhaar-linked payments (ALP) model to speed up the crediting of wages. Given Aadhaar is linked to one’s biometric credentials, the chances of fraudulent data under the ALP are zero. This also lessens the time that the government may require to verify claims from Aadhaar-linked bank accounts.

Today, of the 11.61 crore active workers under the MGNREGS, around 10.16 crore workers have their Aadhaar cards linked to their respective bank accounts. The total funds credited for the MGNREGS via the direct benefit transfer (DBT) mechanism has increased four times from 2015-16 to 2018-19.

A New Lease Of Life For MGNREGS Under The DBT

Firstly, coverage for MGNREGS has improved. As per the data from the muster rolls (muster rolls are similar to attendance registers used to record worker turnout), the number of such rolls has increased by two times between 2014 and 2018.

Two, the wages are now being paid on time. While in 2014-15, only around 27 per cent of the payments were generated on time, in 2018-19, over 90.4 per cent of the payments are credited on time. Aadhaar had a big role to play in this percentage increase. All these payments are credited within 15 days.

Before ALP was implemented, the average amount disbursed per block was Rs 1.82 crore. However, after the ALP-based payment mechanism was implemented, the average amount disbursed per block stands at Rs 3.98 crore. The delay in payments under the ALP-based mechanism is now less than 10 per cent against the 35 per cent in the pre-ALP period.

Three, the demand for work under the MGNREGS has gone up. As stated above, a delay in payments pushed workers to look for work outside the MGNREGS. This is especially true for areas impacted by droughts where the demand for work has gone up by more than 20 per cent. This validates the impact of improved payment system via Aadhaar-enabled DBT for work available under MGNREGS.

The increase in demand for work has been responded to by an increase in supply for work, according to the Economic Survey of 2019. Thus, with the ALP mechanism, not only are more workers finding jobs, but there is also an increase in the work available, resulting in an upward growth of created assets.

Four, in areas distressed by droughts, the number of muster rolls filled increased by a whopping 44 per cent while in areas without any natural calamities, the increase was 19 per cent. The increase in the muster rolls filled across regions validates the increase in the demand and supply of work under the MGNREGS programme.

Five, the Aadhaar-enabled DBT mechanism has been an enabler for the vulnerable sections of our society as well. These sections include the Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes, people with disabilities, and women. After the implementation of the ALP mechanism, the number of rural workers in distressed regions witnessed a sharp upward trend in the post-ALP era against that of the pre-ALP era.

Data-Driven Economic And Social Growth Under A Digitised MGNREGS

The buck does not stop at payments and rural workers alone, for data from the post-ALP era for MGNREGS can be used to derive other conclusions pertaining to distressed districts. Given that there is greater clarity on the supply and demand of work, policymakers can easily identify distressed districts and blocks and take measures accordingly.

The data from the muster rolls and work demand and supply can be linked to real-time metrics like weather, healthcare, education and industry, and thus, an overall analysis of a block or district can be made.

Also, given how infrastructure is going to be critical to the upliftment of rural India where over 750 million people reside even today, the efficiency of payments under the MGNREGS creates room for the creation of more assets.

Further, the creation of these assets can be linked with other government schemes like the water conservation mission under which canals, watershed management, and harvesting structures can be taken up to counter the impact of floods and unprecedented rainfall.

The creation of assets would also enable skill development for rural workers. This would not only increase their incomes but may also drive them towards better employment opportunities at much higher wages than what the MGNREGS may offer. For many, migration to nearby cities and towns could be an easier task once they find themselves equipped with employable skills.

The skill development would further result in overall improvements in their standard of living, aspiration for better education for their children, access to healthcare and much more. In the larger scheme of things, a digital payment system will enable social development for hundreds of millions of people.

Thus, it will not be an exaggeration to say that the MGNREGS has been successfully rescued by a well thought out DBT system. With the JAM (Jan Dhan-Aadhaar-Mobile) trinity seeded in their daily work routine, not only will rural workers find themselves with greater access to public welfare schemes, healthcare, and other formal financial instruments, but also play a far greater role in India’s pursuit of becoming a $5 trillion economy.