Financial Inclusion – Modi’s Tryst With India

Definitely data suggests that even after almost six decades, the redemption of Pandit Nehru’s ‘tryst with destiny’ pledge, in terms of poverty eradication, was not even substantial.

Modi’s tryst with India is taking it places and the poorest of poor are joining the bandwagon in their millions.

The confluence of mobile penetration, biometric identity and the identification and assessment of borrower risk may set the scene for massive credit inclusion process.

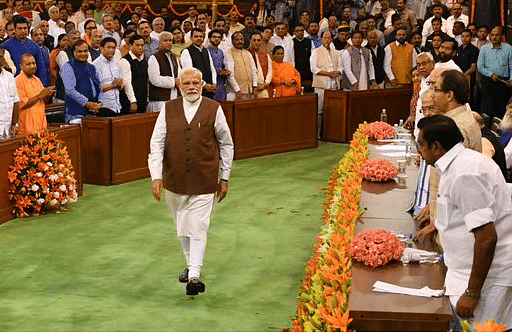

In his second term in office, Prime Minister Modi has talked about making India a US$ 5 trillion economy by 2024-2025. This has not only generated a lot of debate in India and but has also focused world attention on the Indian economy.

Many may think that this might be a tall order for a country that, till recently, was home to the largest number of the utterly poor in the world. But the truth is that India may be closer to this target than we may realize.

While all sectors of the economy have to grow rapidly, the financial services sector has a key role to play to reach the mark. By stepping up its inclusive program that provides equal access to loans and other financial services to all sections of society, it can create a multiplier effect.

The obvious link here is that when a larger number of people borrow, especially the poor, increased economic activity follows leading to growth in sustainable means of income for broader sections of society. This, then helps rupture the “vicious cycle” of poverty.

Public policy planners, to their credit, have long been aware of the direct relationship between financial inclusion and swift economic growth. In fact, in 2005, Dr Y V Reddy, the then governor of the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) had talked about financial inclusion in his annual policy statement. In 2008, the Dr Rangarajan Committee on financial inclusion recommended a national mission to facilitate required policy changes.

Despite all this, India’s progress has obviously been slow in the past. However, the economic fortunes of the poor have changed for the better --- quickly and noticeably --- only in the last decade. A report published in the Times of India (TOI) in January 2019, quoting World Data Lab, showed the steep fall in poverty in India and estimated the current ‘extreme poor’ to be around 50 million. [According to the World Bank, ‘extreme poor’ are those who make less than $1.9 per day.]

It is important to see the declining poverty levels in the context of the massive digital revolution that is taking place in India in parallel. Contrary to what the electronic and print media in India may have you believe, the digital revolution on multiple fronts has aided and catalyzed the financial inclusion programs of the government.

As of December 2018, 1.23 billion people had Aadhar digital biometric identity cards and over 1.21 billion had mobile phones. Also, as of 2017, 80 per cent of adults had a bank account. Bulk of the new accounts were opened with the aid of Aadhar identity cards.

Further, the country has also seen a steep rise in mobile payment transactions. According to the data released by the National Payments Corporation of India (NPCI) transactions via the Unified Payments Interface (UPI), the country’s flagship payments platform, grew by 25 per cent and crossed Rs 1 trillion in value in December 2018.

However, millions still continue to live in poverty. India has a low credit access with only 154 loans per 1000 adults. This may be attributed to the reluctance of lenders to lend to people whose credit worthiness cannot be reasonably assessed. Unlike the US, India does not have robust credit reporting agencies with depth of data that can help lenders in approving loans. This remains a major challenge for credit expansion.

The good news, however, is that the confluence of mobile penetration, establishment of a biometric identity and the emergence of disruptive credit risk solutions that facilitate the identification and assessment of borrower risk may set the scene for massive credit inclusion process. Consequently, India’s efforts to eliminate poverty may have reached a tipping point.

Many financial technology (fintech) companies around the world and in India are now using a consumer’s digital identity to predict loan repayment behavior. In a report published in September 2018, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) of the US has reported that a predictive “model that uses only the digital footprint variables equals or exceeds the information content of the credit bureau score”.

In other words, lenders in India will now be able to assess credit risk of borrowers by using their digital identity. This also simultaneously obviates the need to build credit bureaus using traditional data – an expensive and time consuming effort in any case.

The purpose of this piece was not to speculate if India will reach the US$ 5 trillion mark by 2024-25, but to rather assess its preparedness in setting in motion a host of services and programs that will benefit the largest number of poor. As is obvious, lifting millions of people out of poverty is a multi-pronged, multi-mission driven exercise where the happy meeting of cutting-edge technology and robust political will to execute the mission are necessary and imperative conditions.

India has adequately demonstrated its capability to execute complex projects on time and within budget. This augers well for the extreme poor. If they rise up above poverty, so will India, economically speaking, and crossing the US$ 5 trillion mark may just be one of the milestones.

Modi’s achievements in this regard, as substantiated by data from multiple sources, are substantial and suggest that it is broad-based and truly inclusive. This is in stark contrast to the efforts of the earlier government led by Dr Manmohan Singh, who claimed at the National Development Council that, “the first claim on the country’s resources for development” were reserved exclusively for a particular religious community.

It is indeed debatable if India, in its tryst with destiny, ever managed to redeem its pledge, as Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru dreamt at that midnight hour in 1947. Definitely data suggests that even after almost six decades, the redemption of the pledge in terms of poverty eradication, was not even substantial.

But given the track record of the last five years, Modi’s tryst with India is taking it places and the poorest of poor are joining the bandwagon in their millions. And Modi has the backing of the state-of-art technology. Of course, the claim on the country’s resources for development will be inclusive and for all, and not the exclusive right of a select few.