FM Should Ignore Auto Industry Wimps: Slump Calls For Tweaks To Business Models, Not GST Cut

The auto industry has only itself to blame for its current predicament. In the long-term, it has to stand on its own legs.

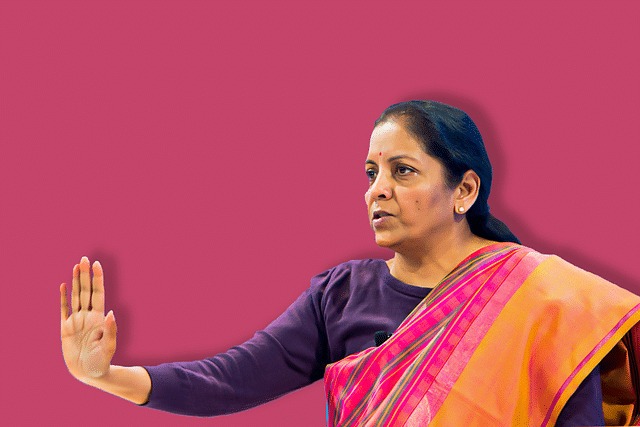

Nirmala Sitharaman would do well to stop listening to the wimps in the industry. If at all GST must be cut, it should be done across-the board for many products, and not just for autos.

The industry needs tough love, and not more mollycoddling.

The continuing automobile sales decline is not going to be reversed by major cuts in the goods and services tax (GST). However, given the rising crescendo of breast-beating over the slowdown, where August saw a dramatic drop of over 41 per cent in car sales year-on-year, 39 per cent in commercial vehicles, and 22 per cent in two-wheelers, the government may well cave in.

It would be a pity if Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman listens to the wimps in the industry rather than the few sane voices in it. One of the rare industry leaders singing a different tune is Rajiv Bajaj of Bajaj Auto, who sees no need for a GST cut right now since all industries face upturns and downturns at various points in the business cycle.

The Economic Times quotes him as saying, “There's no industry that keeps growing forever without correction, so no point chasing that mirage. The answer lies in being global so that the company doesn't fall sick if one market catches flu.”

According to Bajaj the industry is facing the downside of overproduction and over-dependence on the domestic market, and this is borne out by the numbers put out by the Society of Indian Automobile Manufacturers (SIAM), the industry mouthpiece.

In an industry that produces nearly three million vehicles of all kinds annually, barely 16-18 per cent comprises exports. Bajaj and TVS Motors are two of the few who did not depend purely on domestic markets for their sales.

To get a sensible perspective on the industry’s current problems, a flashback is essential. The reality is that the industry has seen more than six years of consistent growth between 2013-14 and 2018-19, with annual growth rates in the range of 4-14 per cent, the last rate being achieved in 2017-18, the first year of GST.

The auto industry, despite relatively high taxes, was a major beneficiary of GST, and this partly explains the huge growth of 14 per cent in domestic sales in 2017-18. The subsequent drop in growth rates in 2018-19 and in the first few months of 2019-20 is essentially a corrective to that spectacular growth.

But such is the quality of media debate on the industry, that all these nuances are lost. Yesterday (10 September), many TV channels were roasting the Finance Minister for mentioning, among other things, that the millennial preference for shared mobility (Ola, Uber) was one of the reasons for the automobile slowdown.

Not one bothered to check if this was true, when Maruti itself made this statement last year (read here), and a Deloitte global study demonstrated that millennials (those born after 1982, and who became adults in the early years of the 21st century) had a markedly different attitude to owning cars when technology (including app-based taxi-hailing services) offered better options.

According to Deloitte's 2019 Global Automotive Consumer Study, 76 per cent of those surveyed favoured the use of connected vehicles, including tech-based taxi service providers.

It noted: “Shared mobility is another trend which is gaining momentum in India. The report uncovers a clear generational divide when it comes to shared mobility.” Younger consumers often question the need to own a vehicle.

But TV anchors made mincemeat of Sitharaman’s statement, reading it out of context, when she actually mentioned shared mobility as only one of the factors behind the auto sales slowdown.

But the slowdown is now big on the media agenda, and political parties are busy attacking the government on this score, even though making cars or bikes cheaper is hardly the solution.

No study carried out anywhere in India has so far claimed that the Indian consumer finds the cost of automobiles to be an inhibiting factor in purchases. When credit is fairly easy, the real deterrents are traffic congestion, the high cost of total ownership, and the availability of alternative modes of commute.

With all state governments now investing more in public transport, more customers may start using them.

An important reason for the slowdown in commercial vehicles didn’t even get mentioned. The sharp drop in truck sales is substantially the result of a huge gain in productivity after the implementation of GST.

With the old octroi and other check-posts gone, turnaround time for trucks has dropped by at least a fifth, which means the same truck can now be used to do more trips per month. Little wonder that demand for new trucks has slowed down.

Another productivity booster was the decision of the road transport ministry last year to raise the permissible gross vehicle weight (GVW) of 16-tonne trucks by about 12-25 percent. This is said to have dampened demand for new trucks even more than the GST turnaround savings.

Duty cuts will not give the Indian auto industry anything more than a short-term lift in sales; the real solutions lie in rethinking business models and strategy.

One is obvious, as a pointed out by Rajiv Bajaj. The industry has to shift focus to exports, with at least a third of sales coming from this route in the medium term. If at all concessions are warranted, it should be in giving the industry a leg up on exports.

Two, the shift towards shared mobility will accelerate if state governments were not so protective towards legacy taxi and auto services. This is bound to change, given the employment potential in Ola and Uber.

When that happens, the industry will have to shift focus away from private sales of passenger vehicles to fleet purchases at slimmer margins. This calls for a modified business model.

This also explains the huge job losses in dealerships. If more automobiles are going to be parts of a fleet and prices negotiated between fleet operators and manufacturers, dealers will play less of a role in future.

Three, electric vehicles (EVs). Even though the government has abandoned plans to ban sales of internal combustion (IC) engine-based two-wheelers and three-wheelers, the gradual shift to EVs is inevitable – mostly in polluted cities.

Again, this calls for a shift in production-mix, for both cars and two-wheelers, not to speak of city buses. ICs, however, will remain relevant in the foreseeable future.

Four, mindless diversifications must stop. One wonders what sense it makes for Mahindra & Mahindra to make two-wheelers when their basic bread-and-butter business in multi-utility vehicles faces strong challenge from rival automakers.

Even within the same categories, automakers who focus on clear market positioning will probably succeed more than those who don’t.

When Bajaj decided to focus on motorcycles, he gave up on scooters, in which Bajaj was a market leader for decades earlier. If Bajaj again gets into scooters, it should clearly do so in another company, with a brand that is differentiated and not linked to its power bikes.

The auto industry has only itself to blame for its current predicament, and to repeatedly ask for duty cuts shows that it is trying to milk the slowdown for its own short-term interests. In the long-term, it has to stand on its own legs.

Nirmala Sitharaman would do well to stop listening to the wimps in the industry. If at all GST must be cut, it should be done across-the board for many products, and not just for autos. The industry needs tough love, and not more mollycoddling.