High Priest Of DeMo, Ken Rogoff, Is Only Half-Right In Critiquing India’s Effort

Unlike other critics who were motivated more by animus towards the Modi government in critiquing demonetisation, Rogoff cannot be accused of bias.

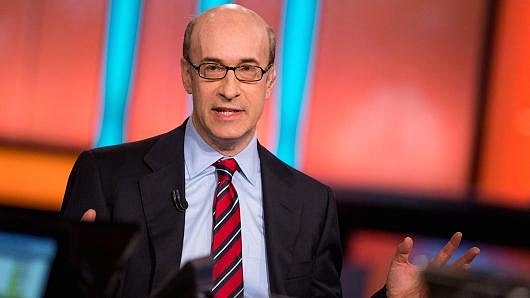

Kenneth Rogoff, a professor of economics at Harvard University, is both an advocate of demonetisation of high value currency notes, and a reasonable critic of the way India has implemented it with old Rs 500 and Rs 1,000 notes.

Soon after India announced demonetisation (DeMo), he wrote in a blog that Modi’s motivation for demonetisation was absolutely right (attacking black money, counterfeiting), but given the lower levels of financial inclusion, the short term pain may be high. But he also admitted that demonetisation can be a golden opportunity for improving financial inclusion.

In his book The Curse of Cash, Rogoff has called for the elimination of high denomination notes (like $100 bills) in view of their large role in illegal trades and the underground economy. He thus specifically advocated gradual demonetisation in advanced economies, but not in developing economies. But while expressing doubts over how well India was executing its own DeMo, he was gracious enough to admit that it could yield even greater long-term benefits than what was envisaged in advanced economies, given that only 2-3 per cent of Indians pay tax.

But some aspects of Rogoff’s views are worth critiquing. Among other things, Rogoff says that demonetisation should not be attempted in developing countries, and, in any case, India’s highest denomination currency note was Rs 1,000 earlier, and Rs 2,000 now. In an interview carried by The Economic Times, he notes that “you did not actually have anything large – your largest was 15 dollars…”. Even now, the largest note is worth $30.

These assertions can be challenged.

First, the logic of saying poorer countries should “not do it at all” is questionable when change adoption is so fast in India. It took us less than a decade-and-a-half for us to move from just a few million mobile phones to over a billion. We will adopt smartphones, which hold the keys to digital money, even faster. We went from poor financial inclusion to near 100 percent - over 250 million Jan Dhan accounts - in less than two years.

We could move from traditional subsidies to universal basic income support – which is just a glint in the western eye even today – over the next few years. All this is possible because technology allows us to leapfrog some earlier steps in digitising the economy and cash usage. Rogoff’s implicit assumption is that low financial inclusion and high use of cash for many informal transactions will trip us. But we could just as easily adopt the high road to digital inclusion.

While the charge of disruption is valid, the presumption that we will take years to shift to digital currency is probably wrong. The chances are, with the right fiscal incentives and disincentivisation of cash in many transactions, India will adopt non-cash modes faster than the world did when the idea was invented.

Second, Rogoff’s claim that our highest value note is worth only $30 is plain wrong. The value of a Rs 2,000 note may be $30 at current nominal exchange rates, but its purchasing power parity (PPP) value is nearly four times more. It is the Rs 500 note which is worth $30 in PPP terms and not the Rs 2,000 note. The old Rs 1,000 note was worth $60 and the Rs 2,000 note is worth $120.

Third, one can’t be sure that the short-term pain will be so damaging either. As Aswath Damodaran, professor of finance at New York University’s Stern School of Business, told Business Standard in an interview, the economists could well be wrong on the negative impact of DeMo. He said:

I have very little faith in economists who tell me that demonetisation will reduce growth. They've never been right in the last decade. While I believe that the effect on black money is going to be temporary, the greater effect of demonetisation is if it creates changes in the financial services system and gets people to shift from cash. And people will change; 10 years back nobody believed that even farmers could have cell phones. Today everybody does. Importantly, if the Indian economy is so fragile that one demonetisation could shake it up, then it didn't deserve to be strong in the first place and I don't believe India is that fragile.

But unlike other critics who were motivated more by animus towards the Modi government in critiquing demonetisation, Rogoff cannot be accused of bias.

His criticism is at least half-right. We would have been better served if we had tried two-stage demonetisation, with Rs 1,000 notes being yanked on 8 November, and the Rs 500 note after two months, when adequate replacement notes had been printed. It would have cause less short-term disruption.