India 2028: The Case For A $6 Trillion Economy Powered By Digitisation

Taking the Indian economy to the $6 trillion mark will not be possible without the involvement of over a billion Indians.

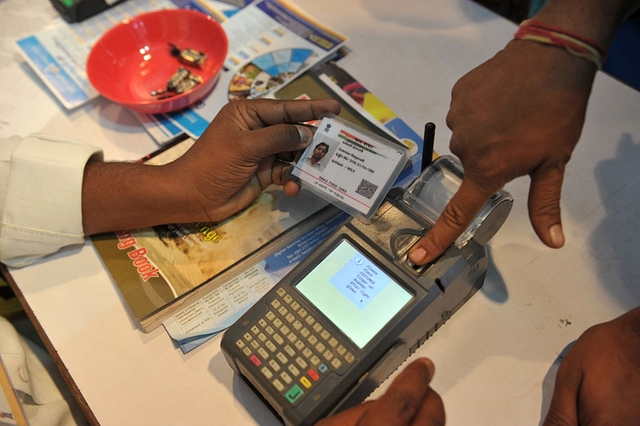

A report by Morgan Stanley last year projected the size of Indian economy to touch the $6 trillion mark from its current $2.6 trillion by 2028. Citing digitisation as the foundation on which India’s economy is projected to succeed, the report evaluated India’s growth prospects taking into account the JAM trinity. However, a year later, several challenges have cropped up. With an Aadhar verdict that leaves a lot to be desired, a data protection law no one seems to be concerned with, and the introduction of Jan Arogya Abhiyan, one wonders if India can fuel its growth through digitisation amidst the political backlash.

Almost two years since demonetisation, an unprecedented decision that enabled the exit of over 80 per cent of India’s cash from the economy over a period of few weeks, the majority opinion is that the move was a failure on the part of the government. However, one of the lesser discussed unintended consequences of demonetisation is the habitual inculcation of digitised payments amongst the urban population that was previously unheard of.

In late 2016, India had its first tryst with cheap mobile data. Even with rising smartphone penetration since the early 2010s which can be attributed to the cheap Chinese companies, a majority of Indians were being charged expensively by the telecom companies. Between 2016 and 2018, the cost of one gigabyte of mobile data came down from Rs. 250 ($4) to as less as Rs. 10 ($0.14). This has resulted in getting Indians online without having to worry about any monetary implications.

The other two components of India’s digitisation were planned ahead of its telecom revolution. With Jan Dhan Yojana, the government embarked on a project of financial inclusion across the nation. Enabling access for every household in the country, the Jan Dhan accounts offered an overdraft facility, micro-insurances to account holders, and most importantly, facilitated the transfer of monetary subsidies like pension funds through Direct Benefit Transfers, taking into account the first component, Aadhar.

While Rahul Gandhi led Indian National Congress may wish to claim the credit for Aadhar, it was Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government that gave Aadhar its ideal and intelligent form. Using the unique identification authentication system to facilitate subsidy transfers and combining it with the goal of financial inclusion, the government took digitisation from the urban alleys to the rural gullies, thus making every household a part of a Digital India.

The buck did not stop there, for a fourth component was ‘almost successfully’ introduced by the government last year in the form of Goods and Services Tax (GST). A revolution in the realm of indirect tax, the emergence of GST saw India move away from a complex and constrained taxation system to a one fueled by centralisation and digitisation.

GST, while rightfully bringing a number of consumer commodities under different tax slabs, shall help enterprises grow. Firstly, with the elimination of inter-state barriers, enterprises can look at reducing freight and transportation costs and durations and lessening warehouse expenses.

Along with the Jan Dhan, Aadhar, Mobile (JAM) trinity, the GST adds to the overall growth of formal economy in India. Given a majority of the workforce is outside the formal economy, it has a direct impact on the percentage of the population paying their taxes. With more people within the purview of the formal sector, credit growth can also see a sharp increase.

Thus, with GST, many micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs) shall see themselves become a part of the formal economy with the elimination of tax subsidies and the inculcation of the input tax credit system over the next few years. However, the exit of subsidies will also see in the inflow of credit as these MSMEs enter the formal sector, thus offering better avenues of growth.

Last week, the government added a fifth component in their pursuit of a better India; Ayushman Bharat or the Jan Arogya Abhiyan. Enabling a health insurance cover for over 500-million people is no small feat. With JAM, GST, and Ayushman Bharat, the government has set India on a path that leads to a $6 trillion economy in 2028. However, setting the nation will not be enough to achieve the status of the third-largest economy in the world.

According to the same report published by Morgan Stanley last year, this digital revolution shall also result in increased investments, enabling India’s market cap to touch the $6 trillion mark by 2027. Given how growth in GDP is directly linked to corporate earnings which further drive share prices, the stock market shall see an increase in investments in the longer run.

Another major winner and contributor to India’s economic growth in the next ten years will be e-commerce players. While urban India is fixated at Amazon and Walmart for now, increased digital transactions, e-KYC (Know-Your-Customer), and increased internet penetration will offer for local players to thrive. Also, one can assume that the number of third-party sellers on Amazon will rise, and if facilitated well through literacy programmes, could enable MSMEs from rural areas to cater to a global market from the comfort of their towns and villages.

The Aadhar verdict delivered by the Supreme Court last week must be taken into context. While individual consent and thriving data protection laws must be the core principles on which the model of digital India is built, excluding private players from accessing the Aadhar database introduces an unnecessary layer of bureaucracy.

Paperless, presenceless, cashless, and consent-based were the components through which the JAM trinity enabled digital inclusion for millions of Indians. Having created open-source application programming interfaces for startups and corporates to use, India Stack, a private entity, created a digital bridge between the consumer and corporates. Thus, a corporate in Kanyakumari could reach out to a villager in Kashmir, such was the potential of these components, open to each and every public and private enterprise.

Pushing out private players in its Aadhar verdict, the Supreme Court has taken a stand that does no good to the prospects of our economy in the coming years. While some blame lies with the government for not taking the front-foot when it came to the narrative on privacy and data protection laws, the exclusion of private players from Aadhar will only slow the economy.

For the future, the government must look at ways of making the entire digital ecosystem more inclusive for private players. Laws must be drafted ahead of their time, especially when it comes to the internet, for the nation shall see over 900-million active internet users in 2028. From fake news to hate speech, the government must look at laws again to prevent a narrative disaster as in the case of Aadhar.

The data law must come into play before the elections of 2019. Critical time has been wasted by the current government to invite suggestions for a law that has been eventually been ripped off majorly from Europe’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). However, the data law must be friendly to the concerns of enterprise, as elaborated here.

The threat to India’s digital pursuit also comes from the prospect of having leaders like Rahul Gandhi in power whose party is infamous for questioning the objective of digital India after Rahul Gandhi’s Twitter account got hacked.

Digitisation, ironically, shall require the good old factor of political stability to succeed in India. The government must also look at a nationwide digital and data literacy programme. From schools to government sponsored educational centres, data and digital literacy must be inculcated in India’s routine for that will be instrumental to the $6 trillion dream by 2028.

Eventually, even with all the digital components in place, the $6 trillion economy size will not be feasible without the involvement of over a billion Indians. From having bank accounts to health covers and from getting their businesses online to attracting greater investments for their corporates, the digital ecosystem in India must be complemented with thriving participation from the people, or else, we could be looking at an underwhelming decade of 2020s in terms of economic growth.