It’s Time We Recognise That Abrupt Policy Interventions Have Catastrophic Implications For Financial Systems

Economic reforms should begin with the telecom sector, where policy uncertainty is a major cause of concern.

A corollary should be judicial reforms, especially in the area of contract enforcement.

Only when faith in the system improves does ease of doing business happen. And this must be taken up on priority.

Every crisis is different and requires a different set of policy prescriptions. However, a template to rule out things to not do is, perhaps, a good one to have. Not setting withdrawal limits should definitely be one of them, as the last thing we want is to stoke panic.

Though the worst of the NPA (Non-Performing Assets) crisis is over, one bank, however, continues to face challenges largely because of factors that are well beyond its control.

The AGR verdict, indeed, has severe implications not just for Yes Bank but several other banks that have exposure to the telecom sector.

The situation is far more complicated as it appears as a waiver of AGR may not be possible. However, even if it is, claiming the amount could kill future growth of the sector.

It is the classic case where we have a golden egg-laying goose, but the last thing to do would be to kill the goose.

In this case, one can’t entirely blame the government as this goose was killed twice by adverse judgments.

First came when 2G Spectrum were cancelled and the second is the AGR one. To be fair, there are evidences in support of the allegation of corruption in the 2G spectrum scandal, which makes companies partly responsible for creating this mess.

However, it is a weakness of our system that those who paid bribes have been penalised while we’re yet to hold those who received them accountable.

The AGR judgement too failed to internalise the costs associated with this decision and its implications for NPAs which would require further provisioning by banks and will prolong the process of our recovery.

The last thing we want is any more elongation of the ‘U’. One can possibly understand why telecom as a sector continues to be a messy one with significant policy uncertainty.

This reveals the urgent need for a systemic overhaul of the sector. The last such overhaul happened under the Atal Bihari Vajpayee government and, perhaps, we should consider another such overhaul of spectrum pricing and the regulatory ecosystem before considering 5G auctions.

A simple band-aid won’t do it, as what is needed is an open-bypass surgery now.

While Yes Bank can’t do much about the AGR judgment, however, raising funds is completely in its purview.

We’ve heard about it for a while now and this makes us wonder how long it will take Yes Bank to finalise a deal with its investors.

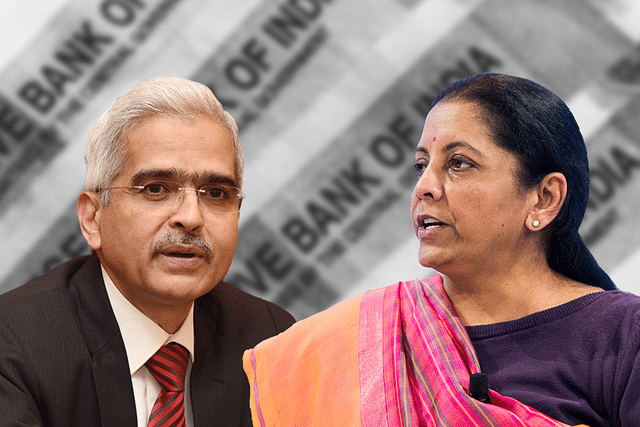

This brings us to the second issue which is to contrast the role of the Fed in the 2008 crisis with the role played by RBI here. The Fed in 2008 pushed banks to raise funds, merged several of them and ended up infusing capital under the Troubled Assets Relief Program (TARP).

One wonders if RBI is willing to step in, if the need arises?

But the larger question remains on the need to recognise how policy interventions, especially abrupt changes can have catastrophic implications for our financial systems.

This is more relevant for several state governments that frequently discard projects set by previous governments, causing huge erosion of wealth.

The same could also be said about certain judgments that don’t duly consider the second- or third-order effects of their decisions.

Indeed, a key lesson in the AGR episode is the recognition of the level of uncertainty that our financial system has to deal with. This reveals an urgent need to invest in state capacity and undertake necessary reforms to our governance structures.

Both of these are important to ensure that such self-goals can be avoided going forward.

One of the most critical governance reforms has to do with judicial reforms as the nature of litigation in economic matters becomes extremely specialised.

We do need a parallel system to deal with economic and quasi-economic matters which does a more efficient job at enforcing contracts — including those with the state.

Similarly, we need to view a judicial system that does not allow judicial processes to be misused to delay justice through endless number of appeals.

A judicial reform can be instrumental in improving India’s image in enforcement of contracts.

Perhaps, the present crisis is the best time to undertake such a decision.

Incidentally, judicial reforms were indeed in the manifesto of the BJP before the 2019 election.

A big mandate like the present one with 303 seats comes with a huge baggage of expectations.

The fact that it seems to be delivering on the most contentious issues in the manifesto in its early days are reassuring, as it raises hopes of a comprehensive judicial overhaul.

After all, if contentious issues that have been pending for seven decades can be addressed with this mandate, then surely issues like judicial reforms and regulatory reforms would be a cakewalk.

The last five years have only shown Modi’s commitment and political will to undertake bold reforms; so the question isn’t if it will be done, but when — The sooner, the better.