Latest GST Cuts Mark Attitudinal Shift From Bird-In-Hand To Two-In-The-Bush

The ideal rate structure the government must aim for is 5-15-25-40, with 15 as the middle rate, and 40 as the exceptional rate for sin and super luxury.

GST is still manufacturing-focused, and not services-focused in an economy, which is more than 55 per cent services.

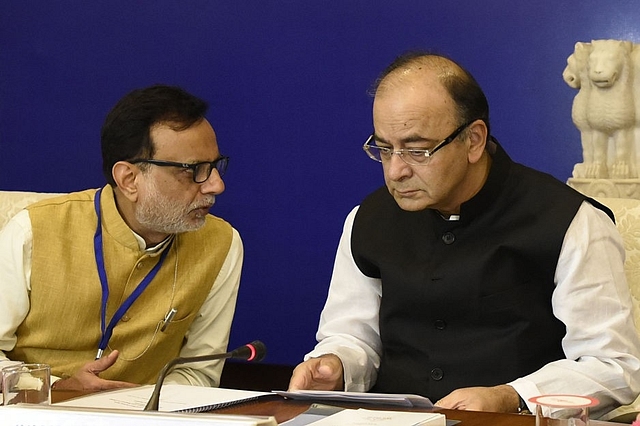

The GST Council’s decision to slash rates on nearly 100 items at its marathon meeting last Saturday (21 July) marks a turning point in the evolution of this complex common tax. It is not so much about the items on which taxes have been cut as the re-emphasis on two decisive shifts in thinking from what was the case a year ago.

For the record, sanitary napkins now attract zero tax, and a whole range of white and brown goods, from refrigerators to washing machines, water heaters, mixies and TV sets (upto 25 inches), will now attract the 18 per cent middle rate. Electric cars are down from 28 per cent to 12 per cent, and many handicraft and leather items are either down to the 12 per cent rate or 5 per cent. The only service to merit some concession is hotel room rates, which will remain at 28 per cent but be charged on the effective tariff, not the rack rate. Fortified milk now gets the zero tax rate, which goes some way to explain the Prime Minister’s statement to Swarajya that milk and Mercedes cannot be taxed at the same rate.

The shift in thinking relates to two fundamental issues that are key to making the goods and services tax (GST) a truly “good and simple tax”, with fewer rates and easier compliance rules.

First, there is now a clear shift away from the old focus on reaching a “revenue-neutral rate”, which ended up being an arithmetic exercise, where state and central taxes were added up to create a new combined rate as close to the original rate as possible. This ended up creating unnecessarily high tax structures for items that are today far from being luxuries. The cuts, which are expected to theoretically involve a “revenue loss” of Rs 6,000 crore – no one can be sure that there will actually be a revenue loss, especially if the cuts are passed on and sales expand to generate more in taxes – but the attitudinal shift is important. It is about letting the GST goose lay its eggs at some point in the future, instead of demanding it all upfront. From 226 goods in the 28 per cent bracket last July, we are now down to a manageable 35 items.

While it is true that many rates were cut in November 2017 ahead of the Gujarat elections, that move was seen as purely a political concession for Narendra Modi’s constituency. But by repeating the cuts, the GST Council has indicated that it does not intend to keep rates high forever, and is willing to let go of the bird in hand – selectively – to get two in the bush. That is the whole point of GST: letting lower rates increase economic activity first and then collecting higher revenues from higher turnover.

The abandonment of the idea of revenue-neutrality is essentially a move away from defensive thinking and that is good. It means Centre and states are now realising that the tax will deliver.

Second, implied in this move to whittle down the 28 per cent slab and move more items to the 18 per cent one is a medium-term commitment to adopting a four- or five-rate structure. Currently, we have four major rates – 5, 12, 18, and 28 apart from zero – and another three exceptional rates, including 0.25 per cent for diamond roughs, 3 per cent for gems and jewellery, and the additional cess over and above 28 per cent on sin goods like tobacco and gutka, apart from super luxury goods like SUVs and personal jets.

In short, we have seven non-zero rates, and these need to come down to five at the earliest.

Logically, this should mean moving the diamond and gems rates to 5 per cent, and creating a super rate of, say, 40 per cent instead of the cess, which is currently levied on more than 50 items, apparently to fund the compensation for states which see revenue shortfalls after GST has come into force.

The cess can be subsumed in a 40 per cent special rate for sin goods and super luxury items, hopefully over the next two quarters once overall revenues stabilise at Rs 1 lakh crore after the current cuts. A 40 per cent super rate is good enough to create the milk-versus-Mercedes optic for political purposes.

The 0.25 per cent and 3 per cent rates will probably have to wait for the general elections to get over in May 2019 before we see movement, since these rates are politically sensitive to the high job-creating gems and jewellery sector, and in Modi’s home state.

The real question-mark is about the one thing that no one is talking about: the choice given to small businesses to opt out of GST altogether through the composition scheme. Some small businesses pay 1 per cent of turnover (or a bit more in some cases) to avoid GST’s complex compliance structure. Most probably this is just a ruse to enable small businesses to conceal incomes from the taxman. Even restaurants end up in the 5 per cent bracket, but without the benefit of input tax credits.

As long as large segments of small and proprietary business are out of the GST net – which means the cycle of paying tax and claiming credit on input taxes is broken – GST will remain sub-optimal. These exemptions need to go ultimately, but before that the compliance burden on small firms should be eased so much that they find benefit in voluntary compliance.

But that change will probably come in stages after 2019. For now, the signal is that GST is on track to become better and simpler than it was on 1 July 2017. It is not yet an unqualified “good and simple tax”.

The ideal rate structure the government must aim for is 5-15-25-40, with 15 as the middle rate, and 40 as the exceptional rate for sin and super luxury. Without this lowering of the middle rate, services – which got screwed after GST – can never provide the kind of economic fillip they need to. GST is still manufacturing-focused, and not services-focused in an economy, which is more than 55 per cent services.