Modi’s Economic Record Is Worth Critiquing, But FT Ends Up Doing A Hatchet Job

The FT editorial board is obviously clueless on the real issues on which it could have hauled Modi over the coals.

It has thus ended up doing a hatchet job born of bias.

The Financial Times (FT) ought to know an economy’s backside from its elbow. And yet an opinion piece by its editorial board on Modinomics betrays no such ability to distinguish between the two. One can understand that the FT, or any foreign publication for that matter, has no love lost for Narendra Modi or the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), but if you find largely failures in Modi’s India, one has to ask whether the pink paper’s editors have allowed their biases to overwhelm their sense of balance, where a fairer assessment of the National Democratic Alliance (NDA) government’s hits and misses could have been made.

The headline, with the statue of Sardar Patel looming above it, says that “Modinomics has yet to deliver for many in India.” (read the full editorial here) This is certainly true, and would be true for almost any government anywhere in the world in an age of economic disruption. Even the best governments would, in fact, fail to deliver for “many” as opposed to the most. But the intro betrays no effort to be fair, and blandly asserts that “the country’s economic growth has been squandered on symbolic projects.”

This is bunkum. You can say Modi’s policies have not helped growth, or even retarded growth, but to claim that it has “squandered” economic growth is a bit rich.

Let’s start with these symbolic projects first. One is the Statue of Unity which cost nearly Rs 3,000 crore to build. And the other is the Ahmedabad-Mumbai bullet train, which will surely be affordable only to the relatively well-to-do. The truth is that neither project has set back the economy in any significant way, with the Patel statue more than likely to deliver in terms of tourism gains what it cost to build and maintain. As for the bullet train, it is being financed by Japan on the easiest of terms, and thus far has not squandered any of the gains from economic growth. The jury will be out on how wise this project is, but it is certainly not a major indulgence that needs criticism right now.

The editorial wanders off into irrelevance right from the start, when it makes a reference to the omission of Nehru’s name in a state-level textbook, and then rubbishes the new back series of gross domestic product (GDP) data produced by the CSO, which shows that growth in the first four years of the NDA under Modi was higher than the average for the United Progressive Alliance (UPA) government. One can suspect that this was politically influenced, but surely its common sense that when you change the base year for calculating GDP, and then try to estimate growth in the past, you will get completely new numbers. And it would not be unreasonable to expect growth in the past to be lower sometimes, for the new series would take newer, growing sectors into account, and weight the shrinking sectors lower. If Sector X and Sector Y contributed to GDP in a 50:50 ratio in the past, and, if, in the new series this ratio is 40:60, with Y more dominant now, will the back data using the new ratio not be smaller?

The editorial correctly criticises “the decision to stop releasing official employment data earlier this year”, possibly for fear of being caught out on an electoral promise “to create good-quality jobs” that “have not been met”, but its conclusion that “many Indians, including much of the large youth population, remain locked into informal and poorly paid occupations” is not wholly true. The one trend that is clearly noticeable from the EPFO data now being released is the increased formalisation of jobs. This may not result in net jobs growth, but the quality of the jobs being formalised in now better. The amendments to the Apprentices Act, and the tweaking of labour rules to allow for fixed-term labour contracts, and subventions on social security payments by employers are the Modi government’s response to low jobs growth, but these will obviously take time to deliver since employer attitudes to taking on more workers at a time of overleveraged balance sheets will be conservative.

It is also right to criticise demonetisation, which impacted growth and the informal sector, but the editorial links it to the liquidity issues now dogging non-bank finance companies – pejoratively lumped together under the term ‘shadow banking’ - as though there is something shadowy about them. This is lazy thinking. The defaults of IL&FS have more to do with poor governance than demonetisation. The concerns over other NBFCs relate to asset-liability mismatches and liquidity, not the quality of their assets. In fact, banks can now buy out these assets and grow their balance sheets quickly, if they want to. Even the Reserve Bank of India is not unduly worried about NBFC solvency.

The editorial, while spotting the downside of demonetisation, makes no mention of its upsides – the huge growth in retail investment in mutual funds, the big increase in the taxpayer base, rising use of digital payments, and the highest direct tax-to-GDP ratio in a decade at just under 6 per cent in 2017-18. Nor does it even mention the goods and services tax, which, warts and all, is the single biggest tax reform ever attempted in India.

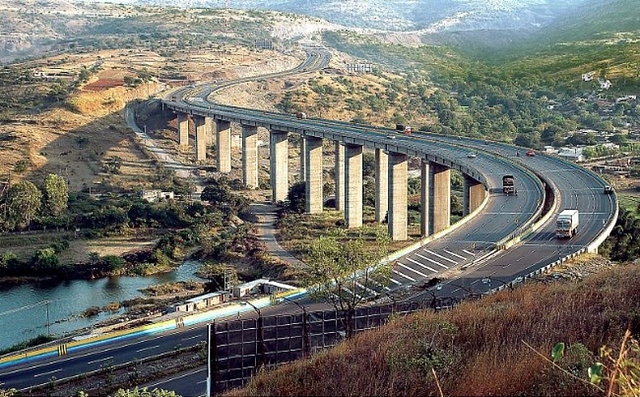

The FT editorial board also argues that “Mr Modi’s other campaign promises, including infrastructure overhauls and improving manufacturing, have not yet been delivered.” This is partly true, but to claim that infrastructure overhaul isn’t delivering is plain wrong. National highways are being built at the fastest rate ever, power is being delivered to the last village, the cooking gas distribution network is now said to cover nearly 90 per cent of households, digital services and telecoms are available to an increasing number of the poor, the Aadhaar biometric ID infrastructure has helped plug leakages in the subsidy delivery system, India’s ease of doing business rank is now 77, more than 50 places higher from where it was when Modi took over in 2014, solar power capacity additions have been over 20,000 MW in the last four years, and will triple again over the next five years, financial inclusion has never been higher, and 80 million toilets have been built in what must be seen as the world’s largest investment in household hygiene infrastructure.

‘Make in India’ is a laggard, but in mobile phones India is already assembling the bulk of them locally; by 2020, 96 per cent of handsets sold here could be India-made. Make for India seems more likely to work, given our huge consumption-driven economy. But one can hardly blame Modi for not reviving Indian manufacturing, given the political class’ inability to push factor reforms in land and labour.

The editorial dismisses one of the biggest reforms to tackle bad loans – the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code – as one of the few “successes under the BJP”, when this has shaken the entire crony culture of our past.

To be sure, there is no shortage of issues on which to criticise Modi. Among them, the failure to tackle the banking crisis earlier must top the list. The botched attempt to privatise Air India, the resort to coercive methods to collect more taxes, the flawed amnesty schemes for tax evaders, the centralisation of decision-making in the PMO, the inability to find more talented ministers to run key economic ministries are some others points on which Modi can be called to account. The effort to force one public sector unit to buy out another (ONGC-HPCL, LIC-IDBI Bank, and now PFC-REC) in the name of disinvestment surely needs critiquing.

The FT editorial board is obviously clueless on the real issues on which it could have hauled Modi over the coals. It has thus ended up doing a hatchet job born of bias.