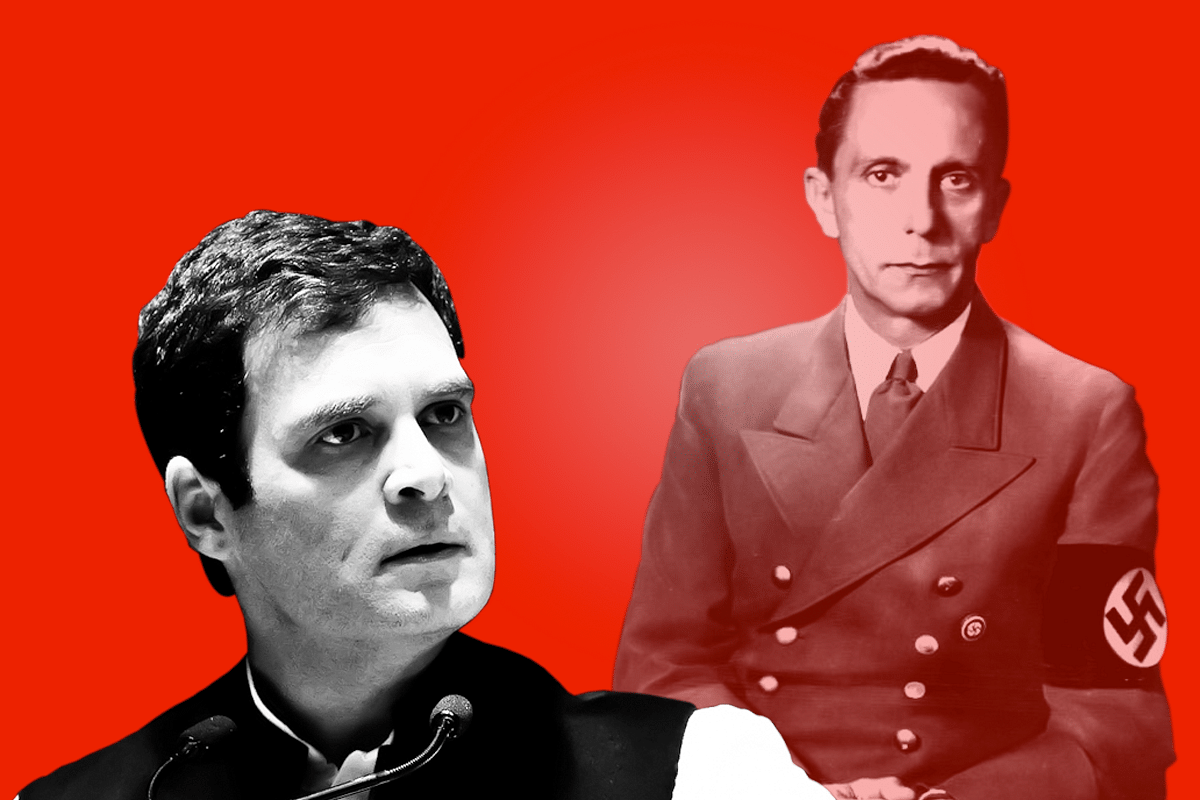

Neither ‘Loot’ Nor ‘Band-Aid’: Primer On RBI’s Rs 1.76 Lakh Crore Transfer To Government For Rahul ‘Goebbels’ Gandhi

Transferring excess capital reserves from the central bank to the government in the larger interests of the financial system and the economy is neither “loot”, nor “Band-Aid”.

It is an investment in stability and growth.

The Congress party, which was run by an ace economist for 10 years, seems to have been over-run by economic illiterates these days. The party believes that the Reserve Bank of India’s (RBI’s) decision to transfer Rs 1.76 lakh crore to the government from its surpluses and excess reserves, is akin to “looting” it.

Interestingly, the party did not think that another Rs 1.76 lakh crore, which the Comptroller and Auditor General of India thought was handed over to private cronies in the 2G spectrum scam, was “loot”. On the contrary, the party’s ace mathemagician, one K Sibal, decreed that there was “zero-loss” to the exchequer. And yet, the transfer of the RBI’s excess reserves, money indirectly belonging to the government as 100 per cent owner of the central bank, is “loot” and not a mere transfer of cash from one pocket to the other.

The party’s out-of-work Goebbels, a.k.a. Rahul Gandhi, provided us with another gem – a quotable quote devoid of economic logic. Transferring some of the central bank’s excess capital to the government was like “stealing a Band-Aid from the dispensary and sticking it on a gunshot wound.” At Rs 1.76 lakh crore, this is a rather expensive Band-Aid. And the idea, that an economy growing currently at 5-6 per cent, can be said to be suffering from a “gun-shot wound” is laughable.

Here’s a reality-check for both the loot-and-scoot critics, and those imagining “gun-shot” wounds to the economy.

First, the taste of the pudding is in the eating. The mere announcement of a transfer of Rs 1.76 lakh crore has brought happy economic consequences, even if only transient. Bond yields are down (10-year GOI is now just over 6.5 per cent), shares are looking perkier (as money gets cheaper, shares get rerated), and the rupee has rebounded against the dollar (from 72.18 earlier, it was hovering around 71.57 around mid-morning on Wednesday).

Second, the criticism that reducing the RBI’s reserves in the short run will lower the bank’s credit rating – a statement made by none other than Raghuram Rajan, a former RBI governor – is questionable. When banks get recapitalised, infrastructure gets more money, the fiscal deficit is kept within bounds, and capital inflows improve as a result of the economy’s improved prospects, the country’s rating will – at worst – remain more or less where it is.

The RBI’s own rating is dependent on how solid the fisc looks, since the government stands four-square behind its central bank. A central bank’s own rating is closely linked to that of the country it represents, and not merely its own capital base.

Even if its rating depended on its own reserves position, the RBI’s contingency and other reserves were a high 25-per cent-plus in 2018, and the Bimal Jalan committee which went into the question of the RBI’s excess capital, called for its maintenance in the range of 20-24 per cent. This is one of the highest in the world. There is no likelihood of the RBI being downgraded anytime soon, unless the capital is continuously depleted year after year.

The former chief economic adviser, Arvind Subramanian, estimated the RBI’s excess capital reserves to be in the range of Rs 4.5-7 lakh crore. So, even after gifting Rs 1.76 lakh crore, a large part of the excess remains excess. There is a huge cushion left even after the transfer of Rs 1.76 lakh crore from Mint Street to North Block.

Third, the assumption that cash transfer from the RBI to government is some kind of expropriation is optical, not real. Let’s first understand where the RBI makes its income from. Nearly 95 per cent of its income comes from interest earnings, most of it from banks and government, including earnings from holdings of US treasury and other foreign exchange-denominated investments.

Roughly one-third of the earnings in 2017-18 came from foreign currency investments, and the rest from holdings on domestic paper, most issued by the government, or from domestic money market operations. While the interest earned of foreign currency assets (on average, just over 1 per cent in 2018) does not belong to the government, a large chunk of the interest earned on government stock and the spread earned on open market operations essentially belongs to the government.

Reason: if there was no RBI, and the government conducted all its debt and market operations through an arm of the Finance Ministry, the money (or losses) would all be its own. The RBI makes money because the government has outsourced the job of managing money to it, and not because the RBI has any intrinsic business model of its own to bank upon.

Additionally, the 4 per cent CRR (cash reserve ratio) of banks’ liabilities that the RBI impounds at zero interest, is essentially money for jam. When it lends this money out to bank, the RBI earns interest on deposits it pays nothing for. And if 70 per cent of the banking system is in the public sector, and hence owned by the government, it means the RBI makes money by impounding a substantial chunk of funds owned by government banks.

This is real loot: it’s like asking you to keep a deposit with me for zero interest, and then lending out the same money to you at a positive interest rate. This is the safest of businesses to be in.

Four, it is the job of the RBI to keep the financial system in good health. But if the RBI’s own finances are in good health and the financial system is sick, at some point either the government or the RBI will have to bail the latter out. A robust financial system is ultimately in the interests of the RBI’s own financial health. So, using some of its excess capital to strengthen the banking and financial system is like investing in your own long-term health.

So, Dear Rahul, Dear Congress friends, transferring excess capital reserves from the central bank to the government in the larger interests of the financial system and the economy is neither “loot”, nor “Band-Aid”. It is an investment in stability and growth.

If Rahul Gandhi really wants to hold the government’s feet to the fire, he should ask for a full account of how it spends the Rs 1.76 lakh crore. That’s really the test for the National Democratic Alliance government when it has got easy access to such a large sum at one go.