PM’s Vote Of Confidence In India Inc Is Welcome; Now Action Should Follow Words

Modi seems to be finally breaking out of his self-imposed need to maintain some distance with India Inc in order to position himself and his party as pro-poor.

By connecting the government’s pro-poor agenda with his new need to improve business confidence, Modi has made the right decision. The poor cannot be helped if the rich cannot deliver higher levels of national income and wealth.

The one thing you cannot accuse the Narendra Modi government of is not listening to public feedback on its policies. If anything, it often listens too intently, and ends up making too many changes that tend to have their own destabilising effects (eg: the frequent changes in the goods and services tax regime).

Over the last one or two years, it has been obvious that India Inc has been unhappy with the government for being unsympathetic to its concerns on the slowdown, tax terrorism, and for inadvertently spreading the impression that all businessmen are crooks.

The Prime Minister made his first move to reach out last year itself, when he met with key leaders of India Inc to discuss policy options in June. But with the elections looming large, he got busy with other priorities and follow-ups were weak.

But after the return of the NDA (National Democratic Alliance) with a thumping majority, the efforts have grown stronger. The first indication of it came in Nirmala Sitharaman’s budget speech, where she had this to say: “We do not look down upon legitimate profit-earning. Gone are the days of policy paralysis and licence-quota-control regimes. India Inc. are India’s job-creators. They are the nation’s wealth creators. Together, with mutual trust, we can gain, catalyse fast and attain sustained national growth.”

Unfortunately, after the budget, when Sitharaman proposed penal provisions, including jail, for companies not complying with corporate social responsibility (CSR) spending norms, this statement of trust was lost in the din. It is to Sitharaman’s credit that she has promised to remove the penal provisions.

Her promise to remove the Damocles’ sword hanging over startups in the form of the 'angel tax' was also overshadowed by the budget decision to increase taxes on individuals earning more than Rs 2 crore. This impacted foreign portfolio investors (FPIs) as much as better off domestic taxpayers. Again, she has shown a willingness to consider real issues about the impact of this tax surcharge, but the moot point is simple: why propose something without considering consequences?

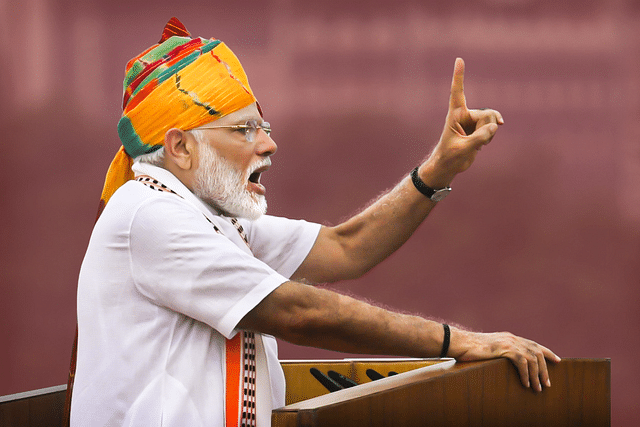

In his Independence Day address from the Red Fort, the Prime Minister could not have been louder and clearer in his vote of confidence for India Inc. The Times of India quoted his longish reference to business thus: “Those who create wealth for the nation…are serving the nation. We should not suspect them and we should not treat them with disdain. It is important that those who create wealth in the country should be given respect and encouraged. They should be given pride of place. If wealth is not created, it will not be distributed, then the poor cannot benefit. Therefore, wealth creation is critical for a country like ours and we want to encourage that. To me those who are engaged in creating wealth are the country’s wealth.”

What this statement indicates is that Modi is finally breaking out of his self-imposed need to maintain some distance with India Inc in order to position himself and his party as pro-poor. Whether this was precipitated by Rahul Gandhi’s “suit-boot-ki-sarkar” jibe in 2015, or frequent references by most opposition politicians to the Ambani-Adani trope, the net result of Modi’s efforts to clean up a corrupt crony system and bring in more tax revenues by demanding higher compliance levels ended up making him seem anti-business. By connecting the government’s pro-poor agenda with his new need to improve business confidence, Modi has made the right decision. The poor cannot be helped if the rich cannot deliver higher levels of national income and wealth.

In his first term, India Inc, which was expecting Modi to unleash his Gujarat model of entrepreneurship-led development on the national stage, found that Modi’s priorities had changed. He no longer was keen to be seen as chummy with business. While this is understandable, India Inc saw him as too distant for their comfort. Hopefully, this trend will be reversed, as is evident from Modi’s I-Day vote of confidence in India Inc.

The way forward for Modi should be obvious.

First, he should set up regular quarterly meetings with businessmen, each time meeting different categories of them. The big boys can be accommodated twice a year, and the small and medium sector the other two times. This can go hand-in-hand with him meeting other important segments of economic actors, from farmers to bankers and finance professionals.

Second, he could set up a panel to look at all pain points of businessmen on the methods used by the taxman to collect dues. While Modi’s government has tried to remove direct calls from the taxman by putting in a layer of technology to facilitate this communication, this obviously can’t be done for big taxpayers, who tend to be handled personally at higher levels of tax administration.

Third, Modi needs to evolve a deeper economic philosophy beyond just talking in general terms about wealth creators and giving them respect. His tax policies rightly emphasise compliance, but a high-tax nation will not be tax-compliant no matter how much you reform tax administration. He needs to commit himself to a much lower corporate and personal tax regime, not to speak of the goods and services tax regime. Also, expectations of raising higher amounts from selling 5G airwaves should be moderated.

Fourth, there is probably a nexus between political funding and tax evasion. Given the high demand for illicit money during election-time from candidates – political parties can still get money through electoral bonds, though these need to be more transparent than now – individual candidates are left to their own devices. Some sort of candidate funding should be a key goal to ensure a cleaner election process. Once the need for tapping corporate slush funds for fighting elections is reduced, the taxman can truly be kept away from most taxpayers.

Fifth, Modi should ask himself whether government actually needs to collect more taxes with higher rates, or lower the drain on public sector white elephants like Air India and Bharat Sanchar Nigam Limited. The public sector owns humongous quantities of land and other assets which can be monetised to make up for any short-term revenue gaps. Over the long term, a higher level of profitable economic activities will anyway deliver higher tax revenues. Once this mental shift is made by Modi – that lowering wasteful expenses in the public sector may deliver as much bang for the buck as higher taxation – half the problems of India Inc would be lower.

Example: the mere existence of Air India in the public sector makes other airlines less likely to be profitable. The recent increase in the industry’s profitability was entirely due to the collapse of Jet Airways.

At the start of his second term as Prime Minister, Modi has to be directly a part of the reset in government-business ties. While government can legitimately demand better compliance, business too has a right to be heard on its genuine concerns. The need to build greater trust between the two has never been greater, at a time when global headwinds from protectionism are posing great challenges. If India is to grow at rates of 7-8 per cent or more consistently, the growth impulses have to come from within in the foreseeable future.